The Red Sea supply chain crisis, which began at the beginning of this year and continued into the mid-year, is expected to turn into a long-term crisis as the Israel-Hamas conflict rages on. The Iran-backed Houthis continue to terrorise the Red Sea, causing the Egyptian government to halt shipping through the Suez Canal, a critical maritime node in the global web of sea lanes of communication, through which 12 percent of global trade and 30 percent of global container traffic traverses annually. Moreover, it is the shortest route from Asia to Europe at a travel time of 12-15 days as compared to the second best alternative, the Cape of Good Hope route, which takes 35 days.

As the Red Sea supply chain crisis continues, the global shipping industry is experiencing congested port traffic at unprepared ports in alternative routes, massive premiums on ship insurance, shipment delays, dramatic rise in ocean freight rates, squeezing profit margins for businesses and a domino effect in various industries dependent on international shipments. For India, the impacts of this supply chain crisis have been minimal in the short term, as compared to the rest of the world. Yet, it is important to underscore the importance of this route for India. 50 percent of India’s gross national exports and roughly 80 percent of India’s Europe exports traverse the Red Sea route, yearly. Using the Cape of Good Hope route results in massive delays and higher insurance and freight costs. For instance, shipping through the Kolkata-Rotterdam route now costs US$ 4,000, up from the pre-crisis freight rate of US$500.

For India, the impacts of this supply chain crisis have been minimal in the short term, as compared to the rest of the world.

In these geopolitically volatile times, it is imperative for Indian economic security to diversify supply chains for a network that is responsive, resilient, and reliable. The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), for the Asia-Europe route, is one of India’s various bids to position India as a vital point in the global web of SLOCs and build a responsive, resilient, and reliable supply chain network. This article tests the viability of the IMEC as an alternative to the Suez route in the medium and long-term scenarios and provides recommendations for enhancing all-around economic connectivity along the route for its efficient operationalisation.

The IMEC’s genesis and problems

The IMEC is essentially a project with geopolitical ambitions, foregrounded in the Abraham Accords, India’s addition into the I2U2 grouping—comprising the United States (US), the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Israel—and the normalisation of relations between the various regional players and blocs in the Middle East such as Iran-Saudi Arabia, Türkiye, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia, among others. These interconnected stabilising events led to the announcement of the IMEC in September 2023 during the New Delhi G20 Leaders’ Summit, by the leaders of the US, the UAE, the European Union, France, Germany, Italy, Saudi Arabia, and India. The corridor envisions connectivity and collaboration through renewable energy grids, free trade zones, hydrogen pipelines, interconnected undersea cables, integrated digital finance infrastructure, and multimodal infrastructure development.

The corridor envisions connectivity and collaboration through renewable energy grids, free trade zones, hydrogen pipelines, interconnected undersea cables, integrated digital finance infrastructure, and multimodal infrastructure development.

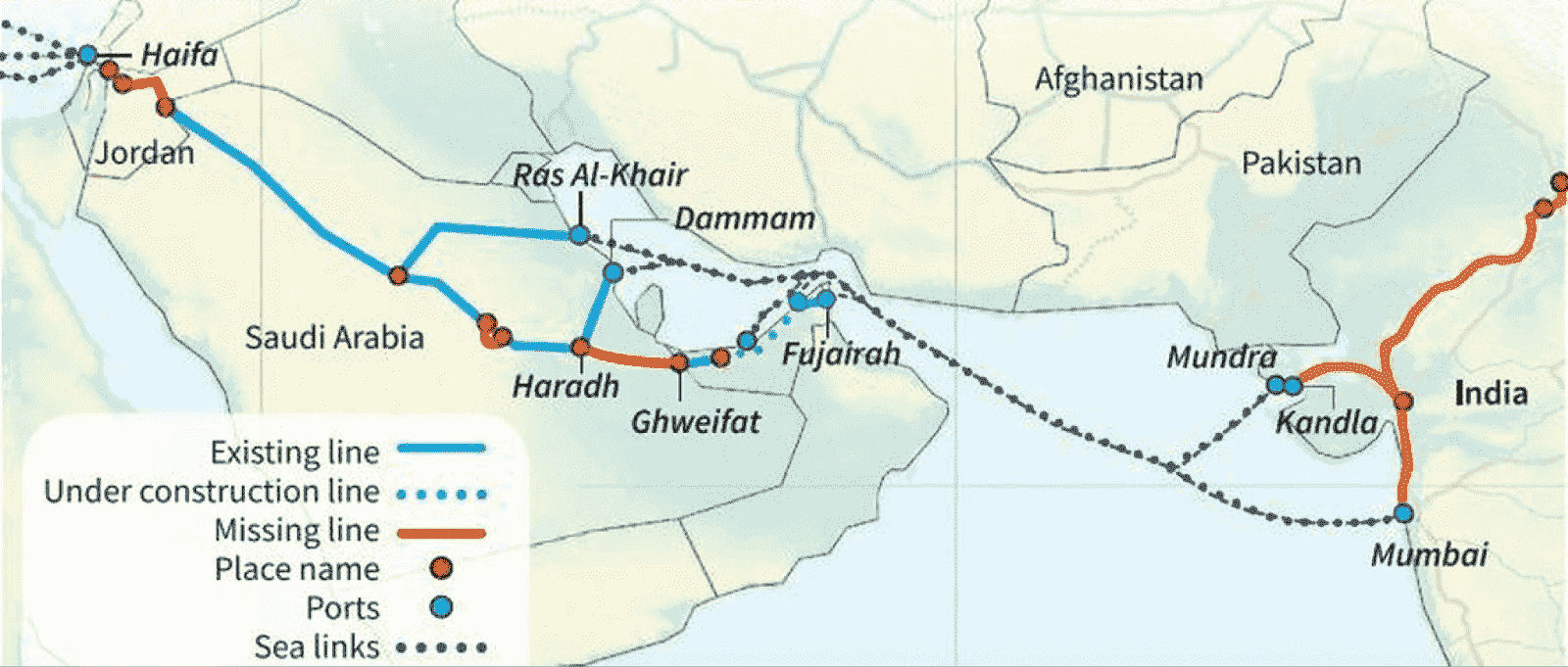

However, problems persist for the IMEC’s actualisation. Riyadh will not further IMEC cooperation until a resolution is achieved to the Gaza and West Bank issue. Saudi Arabia is crucial, because of the railway line component that will run through its territory, connecting the UAE’s Emirati rail to Saudi Arabia and further connecting the Al-Haminda land port in Saudi Arabia to the Haifa port in Israel. However, even if connectivity is established after the war, the Haifa port is riddled with under-capacity, able to handle only one-fifth of what the Mundra and Jawaharlal Nehru Ports in Gujarat (India) can. Another concern is that the Iranians have repeatedly threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz and the Persian Gulf. The IMEC’s Arab ports are all along the Strait of Hormuz, which makes the geoeconomic manoeuvring of “friend-shoring” supply chains redundant, as these ports will always be threatened by any conflict in the Strait of Hormuz and the Persian Gulf at large.

There are also problems of financial integration and free trade among the corridor partners. While India’s India Stack digital public infrastructure has access to the American, French and Emirati fintech ecosystems, the Western economies of Europe and the US are sufficiently financially integrated for easy cross-border transactions and financial flows, corridor-wide interregional financial links and tariff standardisation are missing. Currently, the financial integration and free trade agreements between corridor partners are operational in regional silos, which need intergovernmental consultations and subsequent implementation coordination for corridor-wide operationalisation.

Bolstering economic connectivity

Critics argue that the Israel-Hamas war has derailed the project’s developments. However, the Red Sea crisis has only exacerbated pressures on the Indian government to begin cooperation with the corridor partners for developing the IMEC. India is already progressing with work with Abu Dhabi for port development in the UAE and during the Apulia G7 Summit, the G7 leaders recommitted the PGII’s and Global Gateway’s finance mobilisation for developing the IMEC’s infrastructure. However, this is not enough for a project as ambitious as the IMEC. There needs to be further cohesion in terms of financial and commercial integration, further diversifying routes within the IMEC for hedging against geopolitical tensions and the Middle East’s fragile regional security.

Map 1: The IMEC

Source: The Hindu

IMEC Free Trade Area and fintech collaboration: With US$47 trillion collectively, the IMEC partners are a force to be reckoned with. Yet, economic cohesion cannot be achieved unless there is a standard tariff regime and diversified and low-cost transportation systems along the corridor. Economic connectivity is incomplete without value chain synergisation. If the IMEC partners truly wish to optimally operationalise the corridor, they need to synchronise their cross-border trade tariffs, and transportation systems for commodities and bridge their respective border infrastructures, if required. Another key pillar of economic connectivity is digital and financial connectivity. While the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) is internationally accepted, the Indian United Payments Interface (UPI) can be operationalised for remittances and low-cost retail payments which have high transaction costs in the SWIFT system. However, currently, the UPI is in the nascent state of catering to an international audience. Furthering digital and fintech cohesion can lead to benefits for the agritech, health tech, edu tech and new and emerging technologies ecosystems in partner countries with opportunities for integration in the future.

With US$47 trillion collectively, the IMEC partners are a force to be reckoned with. Yet, economic cohesion cannot be achieved unless there is a standard tariff regime and diversified and low-cost transportation systems along the corridor.

Corridor-wide geopolitical insurance for trade: Regional conflicts such as Russia’s special military operation in Ukraine, the Israel-Gaza war and the conflicts in West Africa, have made hedging against risks difficult for international businesses. For instance, the unprecedented exit of 950+ plus companies from Russia created economic and geopolitical ripples that deeply impacted global supply chain resilience and caused these businesses losses worth 109 billion in FY22. Businesses usually have a range of risks covered under their insurance packages, which are often vaguely worded to include wide-ranging potential contingencies. Mapping geopolitical conflicts and their eruption timelines is extremely difficult for insurers, which subsequently makes price modelling of insurance even tougher. Nowhere are geopolitical risks and threats to regional security more pronounced than in the Middle East and South Asia. Unless the IMEC governments step in as ultimate guarantors, geopolitically motivated harm to businesses can derail the IMEC’s ambition.

Adding more corridor partners: One way of hedging against the geopolitical risks along the corridor is diversifying interoperable routes within the corridor. The IMEC’s eastern corridor, from India to the UAE, offloads at the ports of the UAE. However, these ports are based in the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz, which Iran has repeatedly threatened to blockade. Similarly, as displayed by the Red Sea supply chain crisis, Iran can easily block the Red Sea route too, through its proxies in Yemen. Adding Oman and Egypt to the corridor can diversify routes and bolster supply chain resilience. Oman’s ports are at the Arabian Sea’s shore, Muscat also has good relations with all corridor partners and is the closest Arabian link to India. Similarly, an alternative to Israel’s ports in the IMEC’s northern leg can be Egypt. Egyptian ports on the Mediterranean side can be instrumental for the IMEC and are accessible through Saudi Arabia. On the European end, adding Italy’s Trieste to the ports of IMEC will be pivotal for creating a gateway to Europe. Connectivity with Trieste is imperative for Europe’s trade with the Indo-Pacific. Trieste’s connectivity with Europe’s manufacturing hubs—Northern Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, and Eastern European countries makes it Europe’s entrepôt for trade with Asia.

Conclusion

Although issues persist, the IMEC is a path-building initiative. Corridor partners need to find a resolution to the Red Sea crisis and the Israel-Hamas war alongside standardising policies along the corridor and deepening corridor development. India is already leading development cooperation with the West and the UAE to bolster corridor cooperation. The IMEC is a crucial strategic initiative for India to diversify supply chains and enhance economic resilience. While facing challenges, its potential benefits are substantial. Realising the IMEC’s full potential requires a comprehensive approach, including deeper economic integration, robust financial and digital connectivity, risk mitigation strategies, and expanding the corridor’s network. The success of the IMEC depends on the commitment and cooperation of all participating nations.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Prithvi Gupta is a Junior Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation