Has the backbone of Hamas broken with the death of Sinwar? Yes. Will this mean an end to resistance movements, both militant and political? Most likely not.

The killing of Hamas Chief Yahya Sinwar by the Israeli military in the southern Gaza Strip was an inevitable outcome. Since October last year, a core aim for Israel has been to eliminate, and consequently degrade, Hamas hierarchically. After Ismail Haniyeh and Hassan Nasrallah of Hezbollah, Sinwar was perhaps the final wild card in the deck; the expectation was that now the Israeli military operations could draw down.

However, the exit of Sinwar, Haniyeh, and Nasrallah arguably represents only a part of Israeli thinking, considering similar destruction of leadership had been conducted previously, as seen by the deaths of Abbas Al-Muwasi, Khalil al-Wazir, amongst others. The assassination of Hezbollah and Hamas leadership was always a political decision and not a tactical challenge. Israel has repeatedly shown significant penetration within the ranks of most of these groups and beyond that, even within Iranian polity and society. For years now, Israel and Iran have been involved in a clandestine war. Israel has targeted the Iranian nuclear programme and assassinated scientists inside the country. As part of its counter, over the years, Tehran has built the ‘Axis of Resistance’, a conglomerate of militant groups supported by strategic and geopolitical aims rather than ideology or theology.

Israel has targeted the Iranian nuclear programme and assassinated scientists inside the country.

Israel’s Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, has an odd but important commonality with his nemesis, Iran. While Tehran, with the foundations of its theocratic polity rooted in the 1979 Islamic Revolution, is seen as a quintessential survivalist state, Netanyahu is also seen as a quintessential survivalist politician. Although the current crisis may be the most significant one of his career, which has been marked by decades of moving in and out of power, both graciously and brusquely, it also intricately intertwines with his own legacy and brand.

Since December 2022, Netanyahu has led Israel backed by a coalition with its foundations in far-right Zionist politics, or what scholar Mairav Zonszein has titled ‘Israel’s hidden war’. Before the war, Netanyahu faced corruption charges and mass protests across the country, challenging his government. These internal challenges, highlighted as being seen as an opportunity by Hamas as distractions, were not just political but military as well, with Israeli reservists refusing to show up for volunteer duties.

Tensions between the Israeli military and the Netanyahu government have persisted throughout the war. Defence Minister Yoav Gallant has often been vocally dismissive of some of the decisions being taken. Gallant’s planned trip to the United States (US) was undercut by Netanyahu as a thaw between US President Joe Biden and the Israeli leader took place. The US, politically and militarily, is a lifeline for Israel, even though the current crisis has highlighted this reliance, especially on military supplies, as a major point of weakness for the latter.

Gallant’s planned trip to the United States (US) was undercut by Netanyahu as a thaw between US President Joe Biden and the Israeli leader took place.

On the other hand, Iran’s strategies of the recent past are equally shaken. As the country awaits an Israeli response to the missile strikes it launched to avenge the leadership losses of Hamas, Hezbollah, and the all-powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which ‘manages’ these proxies, Ayatollah Khamenei risks slipping into a conflict which may prove costly. On the sidelines of this military brinkmanship, Iran, however, has mobilised regional diplomacy quite effectively. To rally support, Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi has made whirlwind tours of the region, making their own and the Palestinian’s case. This included a stop in Saudi Arabia, a fundamental foe, but with whom it normalised relations last year after a nearly seven-year gap. The fact that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman met Araghchi showcased the anxiety within the Kingdom as well.

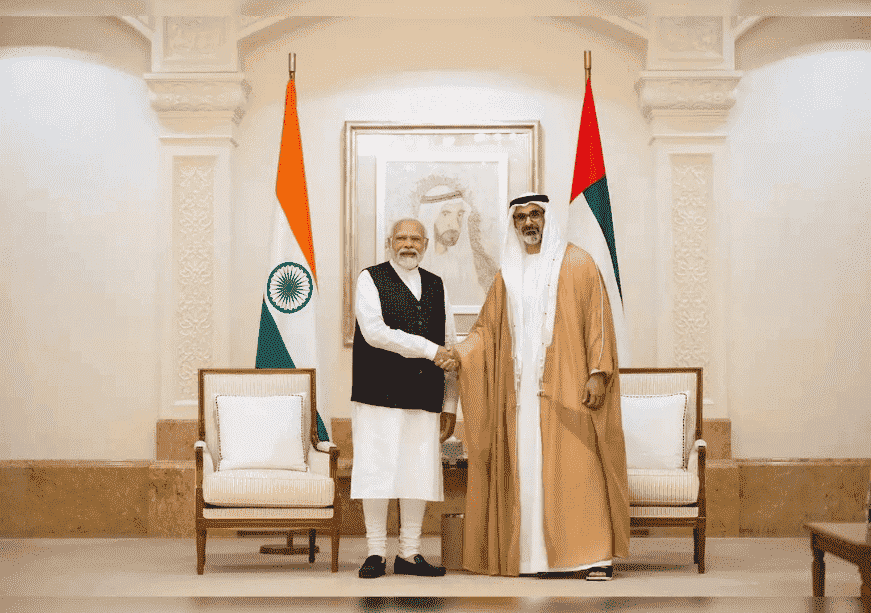

The Iranians have since played smart, mobilising and playing off Arab fears of a prolonged regional war and the costs that would entail, forcing Riyadh into a corner to listen, if not align. Effectively, in the minds of many, Iran is doing what many Arab populations would have expected or wanted Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Egypt to do. That is, push back against Israel as civilian casualties continue to mount in Gaza and Lebanon. Parallelly, newer institutions and instruments of regional politics, such as the Abraham Accords, while strained, have not collapsed even though signatory Bahrain has recalled its ambassador from Israel in response. Flights and commerce between the UAE and Israel continue even as public-facing engagements have been scaled back to mitigate domestic and regional moods.

While the Arab world will not have strong feelings about Hamas’s destructions at the hands of Israel, trying to manage the Palestinian question, resistance, and loosening Iran’s grip on the same is an ideation Arab powers could sell to Israel through already existing backchannels.

But the contestations between Saudi and Iran will also persist. These tensions are institutional, beginning from the Shia-Sunni divide and extending to the struggle for strategic supremacy across the Middle East (West Asia). This tussle may first be visible within Hamas after the death of Sinwar. Hamas, despite gaining from Iranian support, is a Sunni organisation. Any mainstreaming of it towards a moderate bend, moving from a design of ‘Huntingtonian’ civilisation war to one of realistic political brinkmanship, will be attractive to Saudi and UAE and push them to mobilise influence. Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, both Sunni states, have exponentially more economic power than Iran. While the Arab world will not have strong feelings about Hamas’s destructions at the hands of Israel, trying to manage the Palestinian question, resistance, and loosening Iran’s grip on the same is an ideation Arab powers could sell to Israel through already existing backchannels.

Finally, the other side of this conflict may give rise to a ‘new’ Middle East, just not the way it was being envisioned prior to October 2023. Has the backbone of Hamas and Hezbollah been broken? Yes. Will this mean an end to resistance movements, both militant and political? Most likely not. Do current engagements resolve the core issue —the Iran–Israel contestation? The answer is no. The political future of the region remains uncertain even as military realities dictate the escalation ladder, making the ongoing status quo a dangerous one to prevail in the near future.

Kabir Taneja is the Deputy Director of the Strategic Studies Programme at the Observer Research Foundation