US “De-prioritization” of the Middle East

The so-called “Pivot to Asia” was announced nearly 15 years ago, with then-Secretary of State Hilary Clinton announcing that the future of politics would be decided in Asia, not Afghanistan or Iraq. The Obama administration pledged to shift U.S. strategic focus toward the Indo-Pacific, recognizing the region’s growing economic influence and China’s emergence as a global competitor. Throughout the subsequent years, the Pivot was interrupted by crises in the Middle East; the rise of ISIS, the Syrian Civil War, and escalating tensions with Iran pressured the US into maintaining much presence in the region. Despite these interruptions, a broad consensus emerged: the Middle East is no longer the focal point of U.S. grand strategy. Across different administrations, strategic priorities have centered on Europe and Asia, reflecting the overarching emphasis on Great Power Competition.

While the second Trump administration is deeply interested in ending the Gaza War, American policymakers exhibit little interest in significantly reinvesting in the region. Instead, discussions focus on reducing the U.S. footprint, including the potential withdrawal of small troop contingents from Syria and Iraq. Broader debates within the Republican Party reflect a division over global commitments: whether to sustain presence in both Europe and Asia, prioritize the Indo-Pacific, or retreat from global leadership entirely. The Middle East, in a strict sense, is rarely central to these deliberations.

China’s Security Role in the Middle East

This shift in U.S. priorities has fueled discussions about whether China could displace the U.S. as a dominant external power in the region. China has long been an economic powerhouse in the Middle East, with most regional states participating in the Belt and Road Initiative. However, its security role remains comparatively limited. Few experts anticipate China establishing a substantial military presence, as doing so could risk entanglement in protracted regional conflicts—an outcome Beijing is keen to avoid. Thus far, China has refrained from forming formal military alliances, even with close partners.

China views diplomatic mediation as a critical instrument for enhancing its global stature. China has positioned itself as a broker in regional disputes, including its 2023 mediation of the Iran-Saudi rapprochement. China has also expressed interest in mediating Israeli-Palestinian tensions. While there is little evidence that China’s role was critically indispensable in these processes, China has emphasized its role as a “peace promoter.” Additionally, China’s technological capabilities have strengthened its security ties with Middle Eastern countries. Chinese surveillance and military technology, including facial recognition software and drone systems, have been widely adopted by regional states.

The U.S.-China Competition and Its Impact on Regional Security Cooperation

The intensification of U.S.-China strategic rivalry complicates Beijing’s security relationships with Middle Eastern states, many of whom remain key U.S. partners. These nations must navigate two interrelated challenges. First, they must offer sufficient incentives to China to sustain and expand security cooperation, as Beijing’s primary role in the region remains economic. Second, they must calibrate the depth of this cooperation to avoid provoking a backlash from Washington.

Middle Eastern states should seek to create a relatively autonomous space for cooperation within the broader U.S.-China rivalry. A crucial strategy involves encouraging China to separate cooperative engagements from competitive dynamics in its relationship with Washington. If U.S.-China tensions continue escalating into a monolithic zero-sum contest, even seemingly peripheral developments—such as security cooperation in the Middle East—could be interpreted as direct strategic losses for one side.

The intertwining of security and economic dimensions in U.S.-China relations is evident. The U.S. has implemented export controls on advanced technologies, such as semiconductor chips, to impede China’s military modernization efforts. In response, China has accelerated investments in indigenous technology development and pursued a “dual circulation strategy.” Over the last few years, the U.S. has also sought to “de-risk” from China and respond to its weaponization of trade, albeit with mixed results.

Traditional areas of cooperation have also been linked with competition. China repeatedly declined cooperation in climate change, citing U.S. encroachment on its core interests. Issues of nuclear nonproliferation, traditionally an area of superpower cooperation, took a backseat; securing strategic partners such as North Korea and Iran took precedence. For US partners in the Middle East, these developments pose a difficult situation between the two great powers.

China’s Strategic Dilemma in the Middle East

Moreover, China faces a strategic conundrum when engaging in secondary theaters like the Middle East. On one hand, it benefits from diverting U.S. attention and resources away from the Indo-Pacific. Many American strategists argue that the U.S. focus on the War on Terror inadvertently enabled China’s unchecked rise in the 2000s. More recently, U.S. involvement in Ukraine and Middle Eastern conflicts has raised concerns in Washington that deterrence in the Taiwan Strait is eroding. Such diversion presents a window of opportunity for China; even if Beijing doesn’t intend to launch a full-scale military invasion, its coercive leverage would be strengthened by a favorable military balance.

On the other hand, China prefers stability to chaos in its vital economic corridors. The Middle East remains a crucial energy supplier, with more than half of China’s oil imports originating from the region. These shipments largely pass through vulnerable maritime chokepoints like the Bab el-Mandeb and the Strait of Hormuz, both increasingly threatened by regional conflicts and militant attacks. Furthermore, China’s trade with Europe—accounting for 21% of its total exports—also relies on these maritime routes. Given these interests, Beijing has reasons to aspire for Middle Eastern stability.

Middle Eastern states would benefit from reinforcing China’s perception that a secure Middle East is more valuable than one that simply ties down American military resources. First, they could emphasize the potential economic gains that China can derive from security cooperation with regional partners. Predictability and stability are indispensable boons for the shipping industry. Second, Middle Eastern countries could also appeal to the prestige and status that China could gain by acting as a regional stabilizer. Long chastised by Washington as failing to become a “responsible stakeholder,” China could leverage its economic influence in the Middle East to contribute to regional negotiations. China aspires to harness discourse power in the Global South. One approach, encouraged by Middle Eastern partners, could be contributing to peace and stability there. Indeed, China could ultimately find the stabilizing role limited. Nonetheless, even a contributary role from China could be helpful for regional nations.

“Safe Spots” for Security Cooperation

If one aspect of this strategy involves eliciting cooperative behavior from China, the other requires securing accommodation from the US.

Fortunately, the fact that the Middle East is not the primary focus of American foreign policy paradoxically provides regional countries with some room to maneuver. As long as specific modes of cooperation with China do not undermine core US interests, they could potentially continue and even expand them.

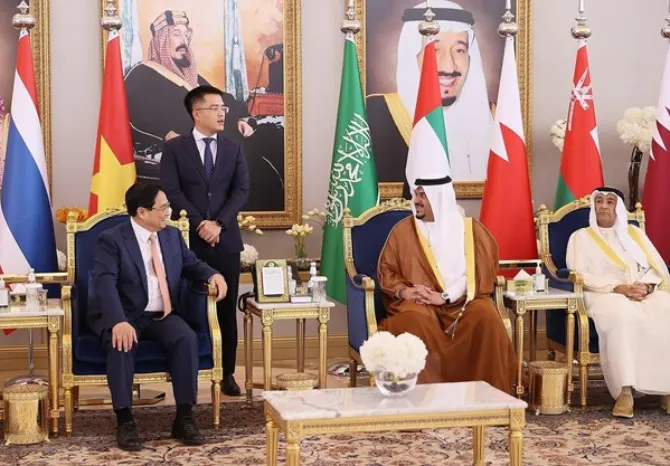

Indeed, American partners in the region appear to be testing the waters. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar have all conducted joint military exercises and training programs with China. Expectedly, Washington is not comfortable with this development. However, as long as these exercises do not involve the exposure of sensitive US military technology or know-how to the Chinese, they are unlikely to pose a significant threat to Gulf-US relations.

In particular, joint exercises focusing on humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) are less likely to raise concerns in Washington than those involving advanced combat tactics. The “Blue Sword-2023” naval special operations training exercise between China and Saudi Arabia focused on overseas maritime anti-piracy operations. Such modes of cooperation would not necessarily cross the red line for the US. Indeed, these activities have little implications for where the US and China might actually be confronted with a military standoff—the Taiwan Strait or the South China Sea.

Counterterrorism efforts represent another potential area for expanded cooperation. There are substantial concerns that Al Qaeda and ISIS could resurge in the region. The relatively nascent regimes in Syria and Afghanistan present significant uncertainties. Joint efforts to counter regional extremist threats could be viewed favorably—or at least indifferently—by the US, as all involved parties share an interest in preventing the spread of terrorism.

Structural Limitations and Risks

One structural challenge remains. The areas where cooperation could be most beneficial are often the areas that Washington views with the greatest suspicion. The adoption of Chinese 5G technology by Gulf states has elicited apprehension from the U.S., citing potential security risks. Similarly, China’s involvement in developing critical infrastructure, such as ports in the United Arab Emirates, has been scrutinized due to fears of dual-use capabilities. Washington also seems concerned about China’s role in the regional sea lines of communication.

While it is no longer as deeply entrenched militarily in the Middle East as it used to be, Washington still remains the single most powerful political and military force in the region. Navigating the complexities of the US-China competition will require a delicate balancing act and a nuanced understanding of the strategic interests of all involved.

Taehwa Hong is a Eurasia Fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute and PhD Candidate in Politics at Princeton University.