While China’s push into Iran is impressive on paper, how Beijing puts this into practice will be the major point to follow.

China’s foreign minister Wang Yi undertook a whirlwind trip of the Middle East (West Asia) last month, covering Saudi Arabia, UAE, Turkey, Oman, Bahrain and Iran. Wang’s trip comes at a crucial juncture, with US President Joe Biden re–evaluating most facets of the China–US relationship, and the Middle East, being a traditional sphere of influence for Washington DC, increasingly looking to hedge its own security and economic interests. Here, Beijing today comes in as a natural actor.

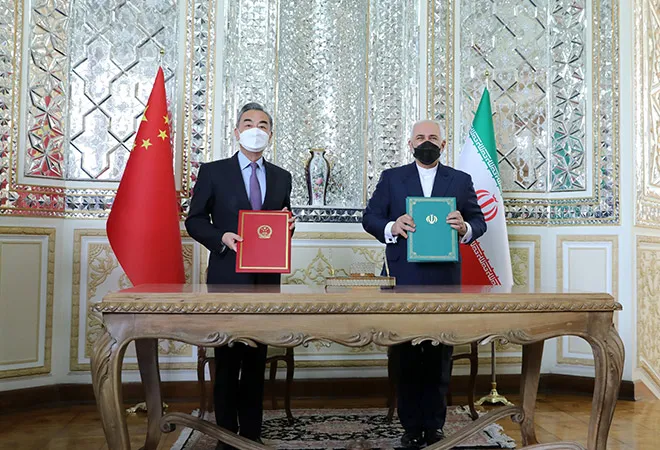

However, the most critical part of Wang’s Middle East jaunt was the stopover in Iran. The foreign minister is the first top ranking official to visit Tehran since President Xi Jinping’s visit in 2016 when the two sides signed a comprehensive strategic partnership agreement. In between, both China and Iran have worked towards an expansive 25–year long programme wherein Beijing will invest in Tehran’s ailing economy, burdened by years of sanctions, in return for China getting unprecedented access to the country’s lucrative but languishing oil and gas sector. This new China–Iran partnership has been envisaged to be worth over US$ 400 billion according to reported estimates. “China firmly supports Iran in safeguarding its state sovereignty and national dignity,” Wang said, adding weight behind the Iranian government.

This new China–Iran partnership has been envisaged to be worth over US$ 400 billion according to reported estimates.

This new China–Iran partnership has been envisaged to be worth over US$ 400 billion according to reported estimates.

These developments come at a juncture when China and the US are embroiled over various geopolitical intricacies, including the Iran nuclear agreement (known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action or the JCPOA), which the US unilaterally exited from in 2018 under the presidency of Donald Trump as part of his ‘maximum pressure’ campaign against Tehran.

The strategic deal between Iran and China gives Beijing a geopolitical edge as far as narratives go. However, the operationalisation of this massive deal is not going to be easy, and China’s commitments seemingly have various ‘strategic exits’ to safeguard both its investments and geopolitical state of play regionally and internationally. To drive this point home further, after Wang left Iran, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijiang answering questions in Beijing on the Iran–China deal said: “The plan focuses on tapping the potentials in economic and cultural cooperation and charting course for long–term cooperation. It neither includes any quantitative, specific contracts and goals nor targets any third party, and will provide a general framework for China–Iran cooperation going forward.”

The operationalisation of this massive deal is not going to be easy, and China’s commitments seemingly have various ‘strategic exits.’

The operationalisation of this massive deal is not going to be easy, and China’s commitments seemingly have various ‘strategic exits.’

The above statement suggests that within the US$ 400 billion umbrella, no specifics have been agreed upon yet between the two sides, making the figure largely speculative and arguably overreaching. It is also imperative to highlight here that despite this development, China’s economic cooperation with the Gulf states still remains much more expansive and operational, highlighted recently by the UAE becoming a regional manufacturing hub for China’s Sinopharm Covid–19 vaccine. However, while the numbers themselves were perhaps constructed to create a narrative, for Iran, this economic push comes at a critical juncture.

Iran, the JCPOA and China

Iran is scheduled to go into elections in June, and with Tehran still working around the change of power in Washington DC, and how to go ahead with the Biden administration, much remains at stake as an overarching deal with Beijing has had mixed reactions within Iran. More than 200 people were reported to have gathered outside the Iranian parliament to protest the pact, with some viewing as Iran ‘selling out’ to China. Beijing has long called for the US to return to the JCPOA accord, while Iran has said that it will not renegotiate the deliverables agreed upon when the agreement was signed between Tehran and the P5+1 states in 2015 under the administration of then President Barack Obama, when Biden was Vice President.

Beijing has long called for the US to return to the JCPOA accord, while Iran has said that it will not renegotiate the deliverables agreed upon when the agreement was signed between Tehran and the P5+1 states in 2015.

Beijing has long called for the US to return to the JCPOA accord, while Iran has said that it will not renegotiate the deliverables agreed upon when the agreement was signed between Tehran and the P5+1 states in 2015.

Within Iran, there is also a plausible tussle around the elections. Iran’s outreach to the West, led by President Hasan Rouhani and Foreign Minister Jawad Zarif, which culminated with the JCPOA, faced stiff internal pushbacks from hardliner factions who did not want a rapprochement, and these divisions are still playing out as Iran mulls over offers to restart talks with Europe and the US. While scholars such as Karim Sadjadpour highlight that Iran needs an enemy such as the US to thrive against, the binding factor remains that all P5+1 participants want to prevent a nuclear bomb in Iran, including China. Iran’s electoral politics is more than often US and Israel centric, so much so that its hardliner lawmakers tabled a legislation in January in an attempt to legally mandate the government to commit to the destruction of Israel by 2040. China, with its new partnership with Iran, will now have to manage a steer away from being labelled as taking sides in the Middle East, especially when it has equally fledging relations with the likes of Israel and its Arab partners via the recently culminated Abraham Accords.

Beijing upgrading its relations with Tehran at this juncture adds critical weight for Iran and its diplomacy. Economic sanctions against Iran have decimated its major industries, specifically oil and gas. In December 2020, the US had installed further sanctions on individual Chinese companies who were continuing to conduct trade of petrochemicals from Iran. Beijing sees this as coercive actions by the US, and by association an opportunity, as Washington DC tightens its strategic and tactical policy tools in the South China Sea and the larger Indo–Pacific region. And the apt reaction against the same from a Chinese perspective, is to further solidify its massive Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) architecture.

Beijing upgrading its relations with Tehran at this juncture adds critical weight for Iran and its diplomacy.

Beijing upgrading its relations with Tehran at this juncture adds critical weight for Iran and its diplomacy.

Beijing’s BRI pitch

‘Balance of power’ considerations compel nations to protect themselves from threats by adding to their own power that of other states through alliances. China sees the following strategic opportunities in its relationship with Iran.

Even as the JCPOA logjam continues, China has stepped into the row. China moving closer to Iran on economic and security issues comes shortly after members of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue — US, Japan, Australia and India — convened for its first–ever summit. Amid an overhaul of Hong Kong’s electoral system, the Biden administration has levied sanctions against the Chinese and Hong Kong. In a separate development, the US, UK, Canada joined hands with the European Union to impose sanctions against Chinese officials and state–run enterprises operating in Xinjiang, in retaliation for its policies against Uighurs. This is significant considering that the first sanctions against Beijing since an EU armaments embargo in 1989 following the Tiananmen Square incident. In light of this, Wang’s tour of the Middle East takes the sting out of the West’s criticism of China over Xinjiang, and signals its pushback against the West using stopovers in the major Islamic capitals.

China moving closer to Iran on economic and security issues comes shortly after members of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue — US, Japan, Australia and India — convened for its first–ever summit.

China moving closer to Iran on economic and security issues comes shortly after members of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue — US, Japan, Australia and India — convened for its first–ever summit.

Meanwhile, political uncertainty in Pakistan has led China to scout for other alternatives. Delays and impediments involving the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) projects in Pakistan may have led to China’s growing interest in infrastructure investments in Iran. Pakistan’s Gwadar port, which China manages, provides it with a shorter route for oil imports from the Gulf vis–à–vis the sea route through the Malacca Strait. Beijing sees Chabahar port in Iran as another option for its crude supplies, which could complement Gwadar. Both port cities also have a sister–city pact, with the Iranians increasingly seeing Gwadar as an opportunity and not a rivalry. China sees Iran as vital to its aim of getting a footing in a region where the US has military bases which seek to check Iranian influence amidst questionable success. Besides, China’s plan to develop Iran’s Jask port which is strategically located near the Hormoz Strait, gives it control over an important sea lane. This can challenge the US naval dominance, and permit China to monitor the US Navy’s Fifth Fleet based in Bahrain.

Conclusion

Despite Wang’s projection behind Iranian interests, a lot more needs to unfold to determine Beijing’s vision in propping up Iran almost exclusively. Unanswered questions, such as whether Iranian expansionism in neighbouring conflicts such as Syria, Iraq and Yemen will be an obstacle for China around its investments in Iran, and how Beijing markets the same with its other potential BRI partners in the Gulf, specifically Saudi Arabia and the UAE, remain. Can the BRI become a common binding between the Shia–Sunni divide in the region? History is usually not kind towards answering this question, and economics alone has proven to be an insufficient interlocuter, as the western example has shown over the decades.

While China’s push into Iran is impressive on paper, how Beijing puts this into practice will be the major point to follow. The Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson stepping away from that US$ 400 billion commitment between Beijing and Tehran a day after Wang left Iran arguably highlights the cleavage between opportunity and risk in China’s Iran outreach.

A rescinding US power presence and regional players becoming more aware and responsible for their own security requirements is going to leave a geopolitical ‘big power’ vacuum.

A rescinding US power presence and regional players becoming more aware and responsible for their own security requirements is going to leave a geopolitical ‘big power’ vacuum.

However, irrespective of the multi–layered questions, China is indeed going to play a critical role in this region over the coming time. A rescinding US power presence and regional players becoming more aware and responsible for their own security requirements is going to leave a geopolitical ‘big power’ vacuum. How Beijing answers this could be a pivotal moment in the region’s geopolitics.

For China, ultimately, Iran is one more square in its ambitious geopolitical chessboard. However, for Iran, the Chinese partnership could be the start of an expansive new chapter altogether if Beijing holds true to its commitment.