Trump’s second-term energy push offers the GCC climate and geopolitical gains, but risks lower oil prices and policy uncertainty that could strain 2030 funding plans

The United States’ (US) domestic energy policy during the first year of Trump’s second term could be considered ambitious and interventionist. However, it remains marked by impermanence. President Trump implements policies by Executive Order rather than passing legislation through Congress, leaving these energy policies vulnerable to reversal by a future administration, or even Trump himself.

For the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), the implications fall into three policy buckets: the push to unleash US energy; disengagement of the US from climate change efforts; and second-order effects of economic policy tools directed elsewhere. On the upside, the Trump administration’s retreat on climate commitments can help GCC sustain fossil fuel exports, resist costly multilateral energy transition initiatives, and most importantly, channel hydrocarbon revenue towards economic diversification. However, the US government’s focus on boosting domestic production of oil and gas sets it up to compete with the GCC for global market share.

Unleashing American Energy

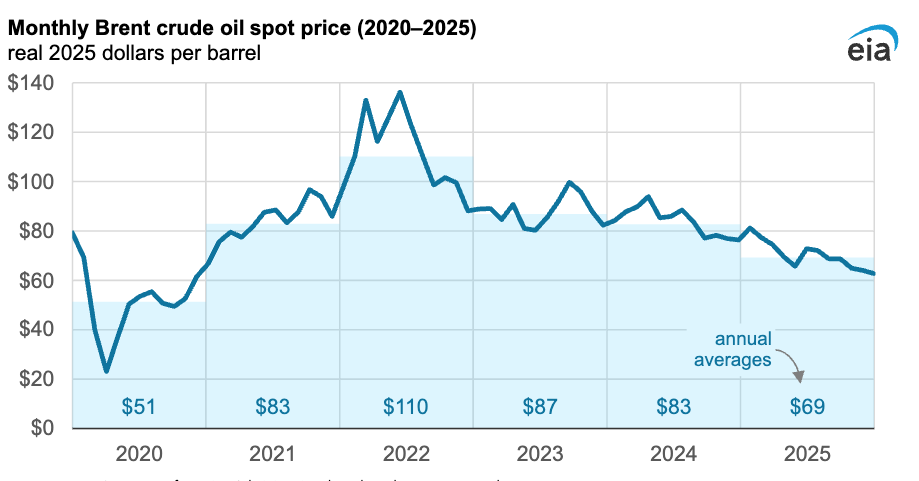

During the initial days of his second term, President Trump declared a national energy emergency and signed an Executive Order calling for the “unleashing of American energy.” The administration’s “energy dominance” policy aims to deliver reliable and affordable energy by increasingenergy production by reducing regulatory barriers and facilitating oil and gas extraction on federal-owned lands and water. While the energy sector has welcomed deregulatory moves, Trump’s repeated calls, sometimes directed at OPEC, to bring the price of oil down to US$50 per barrel of crude have caused anxiety among industry executives. While Trump’s statements underscore the administration’s commitment to the US energy industry, the pursuit of lower oil prices, i.e., US$50 per barrel, would reduce industry revenues. Further, analysts estimate that both US producers and OPEC may begin to cut production when the price per barrel falls below US$55.

Figure 1: Monthly Brent Crude Oil Spot Price (2020-2025)

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, “Short-Term Energy Outlook: January 2026.”

On the demand side, the Trump administration has emphasised increasing the role of hydrocarbons in the energy mix. This has included repealing the Biden administration’s executive orders on clean energy, cancelling funding for green energy, electric vehicles, and related infrastructure, and pulling permits for wind farms. Promoting US artificial intelligence (AI) technologies has become a central part of Trump’soutreach to the Gulf. During his May 2025 visit to Saudi Arabia, Qatar,, and the United Arab Emirates, he was accompanied by US tech executives and had signed deals with Saudi Arabia and the UAE for the large-scale export of advanced chips needed for AI data centres being built by Humain and G42, respectively. Proceeding with such deals supports Saudi Arabia and the UAE in building national tech champions in line with their diversification agendas, without tying these investments to clean energy requirements.

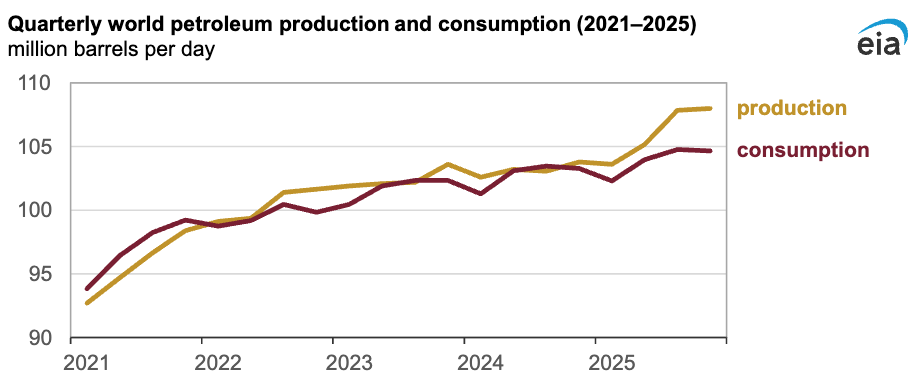

Figure 2: Quarterly World Petroleum Production and Consumption (2021-2025)

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, “Short-Term Energy Outlook: January 2026.”

Uncertainty around the status of Venezuelan oil has resulted in the International Energy Agency revising its global oil supply estimate for 2026 from 4 million barrels per day (bpd), to around 3 million bpd, against a projected demand of 2.4 million bpd. Meanwhile, new LNG projects in the US aim to bring annual export capacity to 130 billion cubic meters (bcm), doubling its LNG exports. Demand for natural gas may remain firmer, in part bolstered by Trump’s promotion of energy-intensive AI technologies.

Multilateral Re-Alignment on Climate Change

US disengagement on climate issues has opened space for the GCC to advocate for a slower transition away from hydrocarbons, while retaining a seat at the table in international climate negotiations. The GCC supports initiatives to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in principle, while also championing energy security and economic prosperity at international fora. At the International Maritime Organization, the US and Saudi Arabia also collaborated to oppose a levy on greenhouse gas emissions intended to support the shipping industry in meeting its net-zero goals by 2050. At the International Civil Aviation Organization, the US also pressed members to reconsider their push towards sustainable aviation fuels.

Washington also opted out of sending a senior administration official to the COP30 climate summit, where Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and other fossil fuel producers resisted attempts to formalise a roadmap for phasing out fossil fuels. At COP30, the Arab bloc advocated for a “dual track” strategy to maintain stable oil and gas supplies that meet global energy demand, while also acknowledging a need to develop renewables and energy efficiency solutions. The bloc pressed to keep discussions concerning the energy industry and phasing out of fossil fuels “off the table” and out of the final COP30 statement.

Second Order Effects of Sanctions, and Weaker Dollar Carry Uncertainty for the Gulf

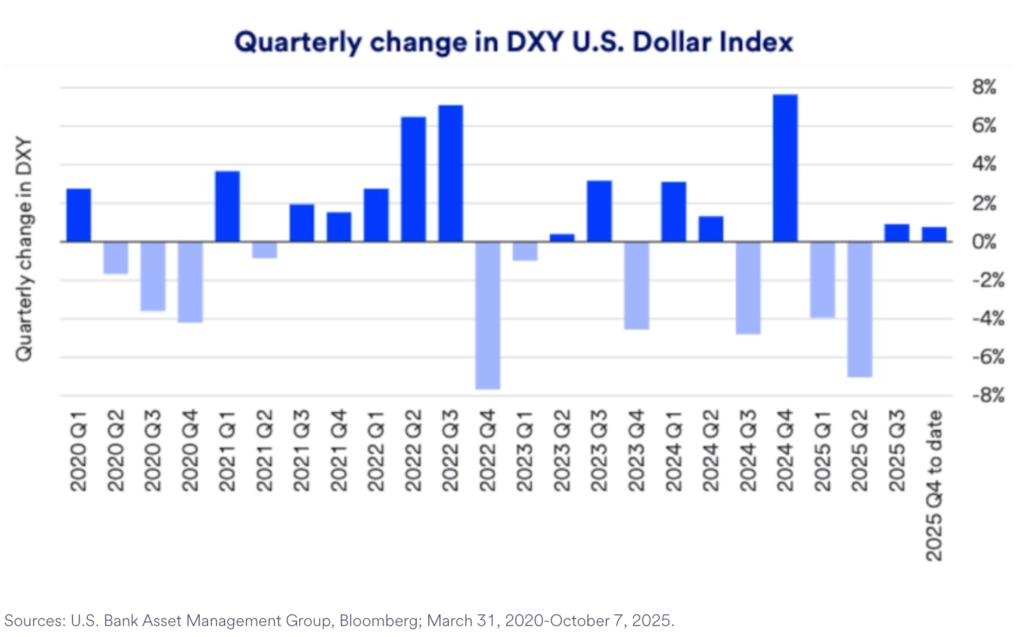

While the GCC states face limited direct exposure to Trump’s tariff policies, the larger impact of trade uncertainty—lower global economic growth, weaker demand in third markets, and intensified competition for market share—will adversely affect the bloc. Slowing economic growth and the associated depreciation of the US dollar threaten to reduce GCC export revenue, complicating funding for national economic diversification programmes. Additionally, the 25 percent US tariffs on steel and aluminium could potentially increase the input costs across the GCC energy, industrial, and construction sectors.

US sanctions policy continues to complicate GCC countries’ management of oil price stability. The US-supported, G7-imposed price cap on Russian oil exports, which was intended to reduce funding towards Russian operations against Ukraine led to increasing price competition between Russian and GCC producers selling to China and India. Russia’s efforts to evade sanctions increased the amount of oil sold outside of OPEC+’s control.

Figure 3: Quarterly Change in DXY US Dollar Index

Source: U.S. Bank Management Group

US Trade Disputes Create GCC Opportunities in Global Markets

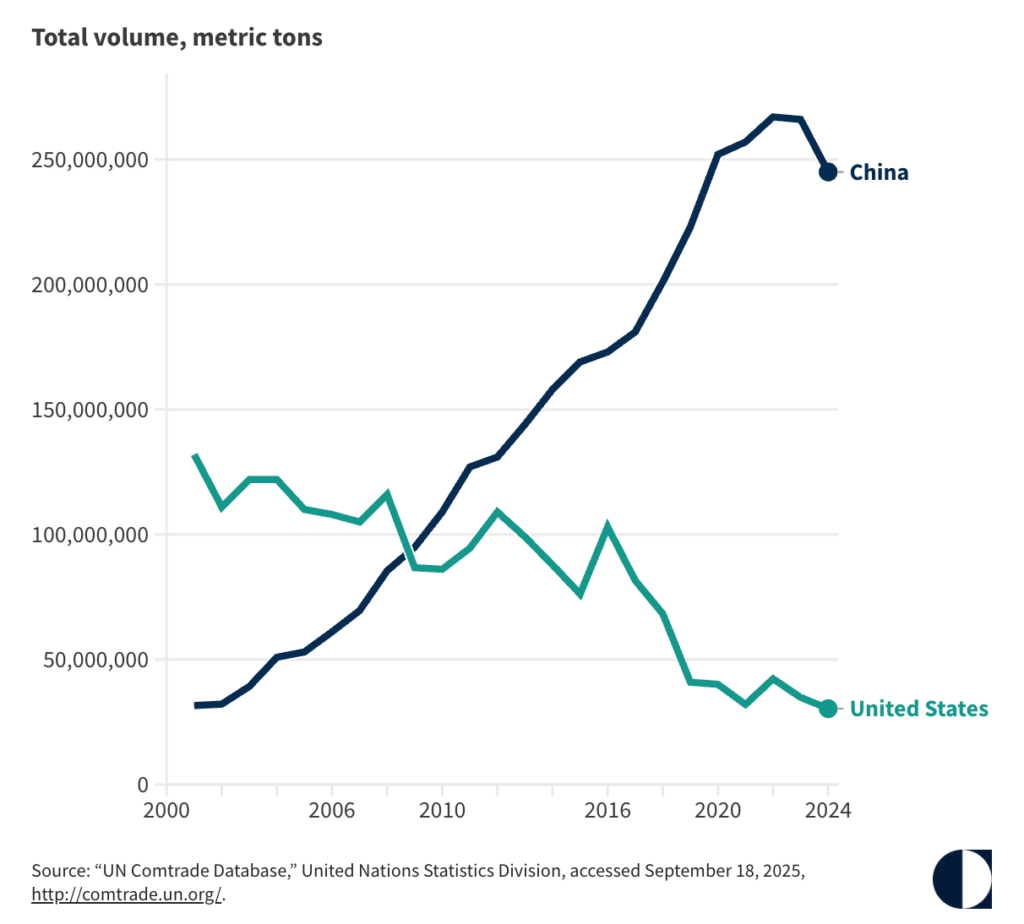

Repeated US tariff hikes and revisions in trade disputes with partners create opportunities for the GCC to sell more hydrocarbons, as India, Europe, and other Asian countries look to diversify energy suppliers. Gulf states benefited from the last US-China trade war in 2017, as China reduced its purchases of oil and gas from the former. East and South Asia’s robust economic growth, primarily driven by China’s growth, generates about one-third of the world’s oil demand at 36 million bpd. China consumes about 15 million bpd, 45 percent of which is supplied by Saudi Arabia, Iraq, the UAE, and Kuwait.

GCC countries, including Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar, have signed long-term supply contracts, welcomed upstream investments, and launched joint ventures in Asia. Saudi Aramco invested in refineries in China and South Korea and is also in talks with India’s Bharat Petroleum Corporation (BPCL) and Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) to invest in planned refineries. Aramco also intends to invest in shipyards in South Korea, China, and Japan to build large carriers and tankers for transporting oil and LNG from the Gulf to East Asia and elsewhere.

Figure 4: China surpasses the U.S. as the top destination of GCC, Iraq, and Iran Exports

Source: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, license: CC BY-NC 4.0.

“Last Man Standing” Strategy Makes Sense for the GCC

The Trump administration’s energy policy outlook and multilateral agenda align well with GCC interests. However, in the medium- to long-term, the Trump administration’s tariff, sanctions, and international climate cooperation policies will have a far greater impact on the GCC. In the short- to medium-term, Trump’s energy dominance agenda, which may include seeking control of Venezuela’s energy sector, and stimulating additional production of oil and gas, will stiffen competition for energy market-share. The increased US output will almost certainly put downward pressure on energy prices and competition between US and GCC producers, as would the erosion of the US dollar, which still dominates energy sales transactions.

Asia’s importance as an export market for the GCC will continue to grow as the U.S. tariff policy reinforces the demand for energy security. Pivoting to supply more oil and gas, concluding future production agreements, as well as the GCC’s investments into refineries and tankers in Asia and Africa, have set the bloc to ride out the short-term uncertainty triggered by US policies.

In the medium- to long-run, low prices for oil and gas or decreased market-share will certainly hurt the GCC’s ability to execute economic diversification programmes, while the US withdrawal from global climate action will allow the bloc to pursue the “last barrel” (sold) strategy in the global energy markets. The GCC’s biggest long-run challenge remains the same: how to deploy hydrocarbon revenues today to build industries capable of sustaining growth long after the final barrel is sold.

Masha Kotkin is an economist specialising in energy markets, climate, trade, and competitiveness.