Despite the narrative of ‘peace’ around the Abraham Accords, it is not to be forgotten that the harbinger of this accord is ‘deterrence’ — both political and military — against Iran.

This article is part of the series — What to Expect from International Relations in 2021.

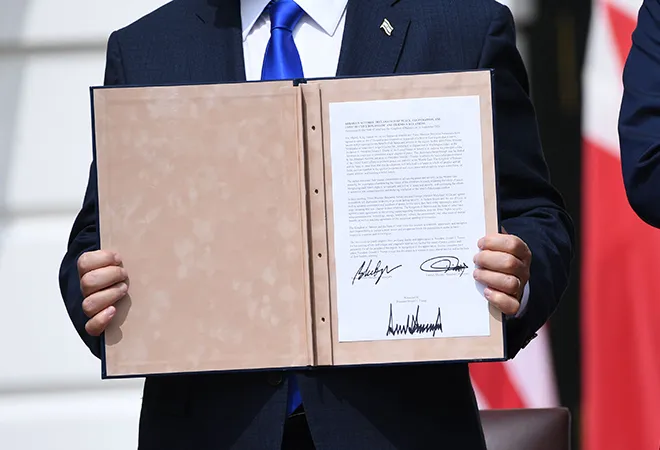

In the final days of 2020, the Abraham Accords, that pushed years of secretive Arab-Israeli talks of cooperation into the mainstream, got a further boost as Morocco announced in December 2020 that it would establish formal diplomatic ties with Israel, joining the UAE, Bahrain and Sudan to become the fourth Arab state to do so.

While political history and geo-economic realities aided by President Donald Trump’s popularity in both the Arab capitals and in Israel helped these processes through, the incoming administration of President-elect Joe Biden may have a much more conservative approach to the Middle East when compared to the relative free hand that the Trump administration offered on many issues. This includes issues like human rights, especially for actors such as Saudi Arabia’s heir apparent, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, whom Trump claimed he shielded during the fallout from the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018.

The incoming administration of President-elect Joe Biden may have a much more conservative approach to the Middle East when compared to the relative free hand that the Trump administration offered on many issues.

Despite the Arab world and Israel’s wishes for a second term for Trump, which many believe may have aided the pace with which the Abraham Accords were finalised and expanded, it is the question of Iran that remains the nucleus of these diplomatic manoeuvres. The coordination has been palpable between the US and allies in the region, beginning with the assassination of Iran’s celebrated commander Gen. Qasem Soleimani in January 2020, a reported assassination of senior Al Qaeda leader in Tehran in August 2020 (which Iran denies), and the assassination of noted Iranian nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizade in the outskirts of Tehran in November 2020. The assassination of Fakhrizade brings back the era beginning in 2010, when more than four noted Iranian nuclear scientists were assassinated, allegedly by Israel, to stall Iran’s nuclear ambitions and to derail the West’s nuclear negotiations with the country which eventually led to the 2015 JCPOA agreement.

Trump withdrew the US from the JCPOA in 2018, much to Israel and the Arab world’s delight. Now, the Biden administration, staffed with Obama-era protagonists, is expected to get back into negotiations with Iran. This is going to become the main challenge between the US and the Middle East, from regional peace to even the success of the Abraham Accords itself. However, the next few years will not only be about these dynamics, but also how Iran navigates its own polity. With elections in the Islamic Republic slated for mid 2021, familiar divisions have already surfaced, with Ayatollah Khamenei backed by the IRGC returning to the traditional anti-US stance with gusto, while President Hassan Rouhani voting to veto a bill by his country aimed to boost uranium enrichment, while suggesting Iran is willing to return to the 2015 JCPOA agreements as it reels under sanctions once again.

Despite the Arab world and Israel’s wishes for a second term for Trump, which many believe may have aided the pace with which the Abraham Accords were finalised and expanded, it is the question of Iran that remains the nucleus of these diplomatic manoeuvres.

However, for the Biden administration, the challenges also remain mammoth. As the US struggles with the COVID-19 pandemic, a challenging global economy and domestic political fissures, Biden is expected to concentrate significantly more on the US, and not as much around big, bold foreign policy overtures. However, he is still expected to give priority to the JCPOA, which raises anxiety amongst the Arab capitals along with Israel, leading to consolidation of both power and interests to develop mechanisms to deal with Iran sans a strong American hand at play.

Despite the narrative of ‘peace’ around the Abraham Accords, it is not to be forgotten that the harbinger of this accord is deterrence — both political and military — against Iran, which despite its economic troubles, has made significant strides using asymmetrical tactics and implementation of militias across theatres such as Syria, Iraq, Yemen and so on. Over the next year specifically, further clarity on the Biden administration’s overtures and Iran’s willingness would define whether the centrality of peace and stability woven around the Accords is sustainable or not.