Lebanon’s IMF deal remains stalled as political and financial elites resist reforms, deepening the country’s economic paralysis amid dollarisation.

Lebanon’s Economic Collapse and the Rise of Dollarisation

The Lebanese economic downfall has been ranked by the World Bank as the third most severe economic collapse worldwide since the 1850s. This is a direct consequence of the catastrophic sovereign default and the banking sector collapse of 2019. The subsequent hyperinflation of the Lebanese Lira and the imposition of informal capital controls by Lebanon’s Central Bank effectively destroyed public trust in the national currency and the formal financial systems. In the resultant vacuum, a pervasive dollarisation of its cash economy had taken hold, not as a matter of policy, but out of necessity. This has led to a dualistic economic structure that is resilient, but limited, where the informal cash economy operates exclusively in US dollars, masking the paralysis of the formal state. A narrow segment of the population with access to external dollar inflows sustains the consumer market, operating in parallel to a defunct national economic infrastructure where public services are largely absent and the formal banking system is non-functional for the majority of citizens.

The only conventional path to stabilisation is a multi-billion-dollar programme from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that remains stalled, despite reaching a staff-level agreement in April 2022. This is due to the failure of the Lebanese authorities to deliver the reforms demanded by the IMF to provide the funding.

IMF Conditions for Reform: Progress and Political Resistance

The agreement is more than just a potential financial lifeline. It is a clear, internationally endorsed roadmap for recovery. The proposed US$3 billion, four-year Extended Fund Facility (EFF) is, in itself, a modest sum relative to the scale of Lebanon’s financial collapse. However, its true value lies in its role as a catalyst to unlock a far larger international resources package and to signal global markets that Lebanon is once again a credible partner for investment. However, the disbursement of these funds remains contingent on the Lebanese government implementing a series of critical reforms. It is the sustained political resistance to these very actions that explains why the agreement has reached a stalemate.

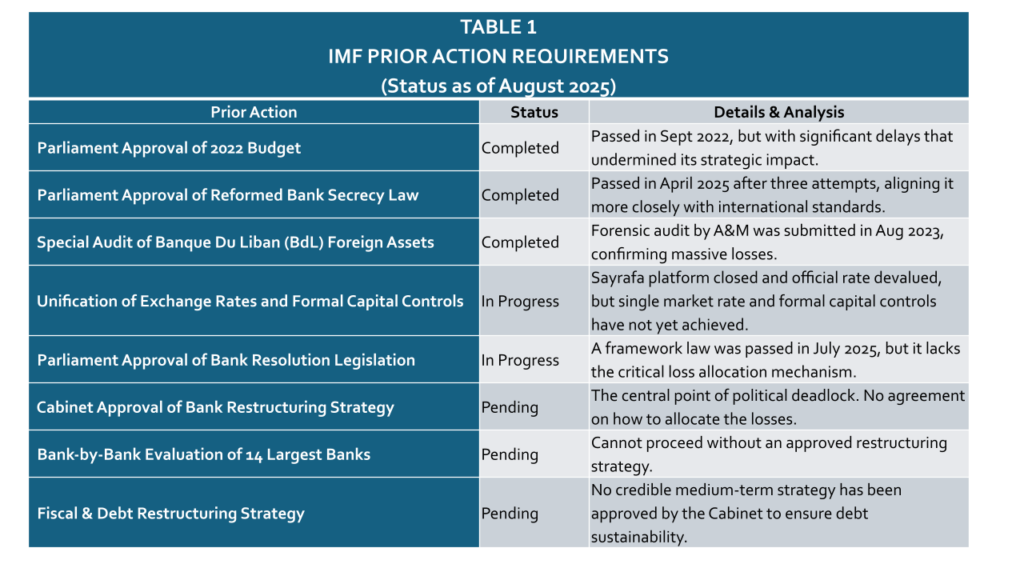

The IMF’s prerequisites are the foundational pillars required to rebuild an economically shattered Lebanon. At the forefront is the demand for the Cabinet’s approval of a bank restructuring strategy that recognises the sector’s large losses while protecting small depositors and limiting the use of public resources. This is to be supported by Parliament’s approval of an emergency bank resolution legislation to implement this strategy, alongside the initiation of an externally assisted bank-by-bank evaluation for the 14 largest banks. To enhance transparency and combat corruption, the plan requires Parliament’s approval of a reformed bank secrecy law aligned with international standards and the completion of a special purpose audit of the Banque Du Liban‘s (BdL) foreign asset position. On the macro-economic front, the IMF mandated Cabinet approval of a medium-term fiscal and debt restructuring strategy to restore debt sustainability, complemented by Parliament’s approval of the 2022 budget to regain fiscal accountability. The framework requires the BdL to unify exchange rates, which is essential for enhancing economic activity, supported by the implementation of formal capital controls.

There has been a renewed push to meet these conditions and secure an IMF loan as Lebanon’s newly elected president and prime minister, both of whom took office in early 2025, have pledged to prioritise reforms and secure an IMF financing agreement. In March 2025, another IMF fact-finding mission visited Lebanon after the country’s authorities requested a new IMF-supported programme that could aid their efforts to address Lebanon’s significant economic challenges. While progress is being made on the conditions outlined by the IMF, this progress has been “very slow”, as noted by IMF Mission Chief Ernesto Rigo. It is important to understand the progress made so far and the financial factors dictating the incentives for the Lebanese elite negotiating the IMF deal.

Selective Implementation and the Stalemate Ahead

An examination of Lebanon’s progress on the IMF’s prior actions, as detailed in Table 1, reveals a pattern not of simple failure, but of selective implementation. The reason this programme remains stalled is that these conditions are not merely technical hurdles, but political ones. The Lebanese parliament is highly fragmented, where 17 parties are represented, yet 12 of them hold five seats or fewer. Analysts have argued that the dominant political blocs were never genuinely committed to pursuing the IMF programme. The reforms proposed by the IMF present a direct challenge to the established political and financial interests that are deeply intertwined with the existing economic framework.

While the parliament did eventually pass the 2022 budget in September of that year, its passage nine months into the fiscal year rendered it a largely irrelevant accounting exercise instead of a forward-looking fiscal strategy. It could be viewed as ticking off the checklist to show compliance, but it lacked any of the deep, structural reforms needed to restore fiscal accountability. Furthermore, a strengthened bank secrecy law was enacted in April 2025 after three contentious attempts. While the IMF acknowledged this as progress, its real-world impact remains questionable. A law is only as strong as the political will to enforce it. In a system where the regulatory bodies are subjected to intense political influence, the passage of the law is a necessary but not a sufficient condition to ensure transparency.

It will be important to audit transactions and reasons for losses to establish fair accountability. This lack of accountability was evident in the 2023 forensic audit by Alvarez & Marsal of the BdL as required by the IMF. Its findings confirmed that the central bank’s former governor, Riad Salameh, had unconstrained discretion as he pursued costly financial engineering policies. However, no significant corrective action has been taken since, and attempts have been made to politically neutralise the report.

Two further actions are technically ‘in progress,’ but their implementation has been slow. Lebanon has inched towards exchange-rate unification but has not yet completed it. Since late 2023, the central bank has wound down the controversial exchange platform Sayrafa that the World Bank estimated had generated over US$2.5 billion in arbitrage profits for those with privileged access. This move, coupled with the narrowing of multiple rates, has been noted by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development as part of a broader attempt to stabilise prices.

By contrast, a statutory capital-controls law has still not been enacted, as it will significantly prevent preferential treatment to certain powerful depositors who might be able to transfer funds outside Lebanon, while most of the population cannot access their deposits. Instead, the authorities have relied on ad-hoc central-bank circulars such as Basic Circular 169 sent out in July 2025 to ration transfers and withdrawals. This approach leaves legal uncertainty in place and falls short of the IMF’s call for formal controls. In short, arbitrage opportunities have narrowed compared to the Sayrafa era, but the legal infrastructure to eliminate them comprehensively is still missing. Another prior action, which is in progress, is the enactment of a bank reconstruction legislation in July 2025. This has created a sophisticated set of tools and a dedicated authority to manage failing banks. But the law will not be implemented until another ‘financial gap’ bill is passed that will decide what shares of the losses will be repaid by banks versus the state. Hence, the legislation is notable for omitting a mechanism for loss allocation that constrains the law’s effectiveness and leaves unresolved conflict over loss distribution.

What Lies Ahead for Lebanon’s IMF Recovery

The remaining prior actions are not just delayed but have hit a wall as they cut into powerful political and financial interests. The approval of a bank restructuring strategy is the central point of contention. The IMF requires the bank to recognise upfront losses of estimated US$70 billion, protect small depositors, and limit taxpayer money, while putting the major burden on the bank shareholders. Lebanese banks, on the other hand, argue that the losses should be borne by the state, citing decades of unsustainable financial policies and corruption. They called certain parts of the IMF draft ‘unlawful’ as it could wipe out shareholder equity, and wealthy depositors could face bail-ins. These changes have been resisted by the banks’ lobby, even branding elements of the IMF draft ‘unlawful’. When the courts sided with the depositors, the Association of Banks staged shutdowns, signalling its influence over the pace of reforms. Furthermore, the initiation of an externally assisted bank-by-bank evaluation remains pending as the international firms are reportedly reluctant to work in Lebanon, given its reputation. Similarly, the Cabinet has been unable to approve a credible medium-term fiscal and debt restructuring strategy. This inaction signals a continued focus on short-term crisis management over the long-term structural reforms needed to restore debt sustainability and regain the confidence of international markets.

Lebanon’s selective implementation of IMF reforms reveals that the economic stalemate is not a result of state incapacity, but rather of a structural paralysis, driven by political and financial interests. The political establishment has demonstrated a capacity to pass complex legislation but has left these frameworks ambiguous. A path to recovery will require a fundamental shift in the incentive structures that currently favour the continuation of the status quo.

Samriddhi Vij is an Associate Fellow, Geopolitics at the Observer Research Foundation- Middle East.