This article is part of the series—Raisina Edit 2024

Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) is a buzzword that militaries worldwide are familiar with. Each generation of the military encounters and adopts new technologies that intersect with changing doctrines, strategies and tactics to bring about irrevocable changes in the character of warfare.

Every major war fought in the 20th century experienced an RMA. The deployment of the machine gun changed the nature of trench warfare during World War I, as did the blitzkrieg tactics and highly manoeuvrable tanks and mechanised platforms of WWII. During the first Gulf War, the United States brought the idea of RMA to the forefront by using its high-tech stand-off capabilities, including Tomahawk cruise missiles and carrier-based air power to effortlessly rout Saddam Hussain’s army.

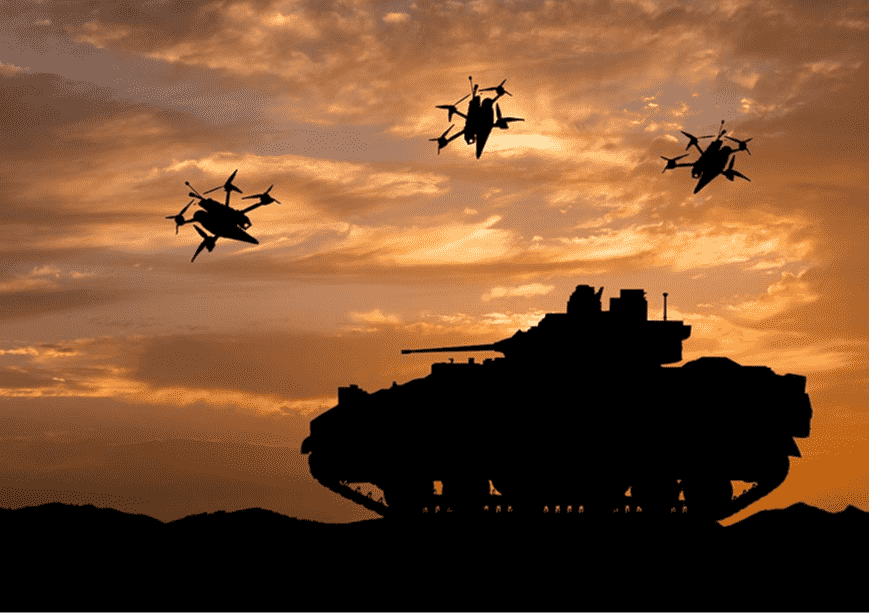

Today, network-centric warfare has taken centre stage. Artificial intelligence (AI), space and cyber realms are fusing with sensors, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) and beyond-visual-range (BVR) weapons on the modern battlefield, drastically reducing Sensor To Shooter (STS) kill chains.

The deployment of the machine gun changed the nature of trench warfare during World War I, as did the blitzkrieg tactics and highly manoeuvrable tanks and mechanised platforms of WWII.

The battlefields of yesteryears hold many lessons. Modernisation is a process. Technological and doctrinal advancements as well as corresponding transformation in organisational structures are add-on layers.

The global situation today is characterised by instability and uncertainty. Trade and technology have been weaponised. Territorial disputes have acquired salience as witnessed in wars between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Russia and Ukraine, and, more recently, the conflict between Israel and Hamas in Gaza.

The first lesson of the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan is the overwhelming difference that drones can make on the battlefield. With an archaic and disjointed air defence system, Armenia simply had no answer to the havoc wreaked by Azerbaijan’s Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 drones and Israeli kamikaze drones on its troops and tanks. Azeri UAVs successfully destroyed many Armenian air defence systems, which appeared to lack electronic warfare (EW) capabilities.

Drones are cheap to acquire and operate. The smaller ones can be carried by individual soldiers and deployed on the battlefield. Drones have firmly established their place in an era of network-centric warfare, especially during the war in Ukraine. Ukraine’s deployment of Bayraktar TB2 drones initially proved effective against Russia but also spurred the development of counter drone systems down the line.

The smaller ones can be carried by individual soldiers and deployed on the battlefield. Drones have firmly established their place in an era of network-centric warfare, especially during the war in Ukraine.

The Israel-Hamas war, like the war in Ukraine, led to unexpected lessons from the battlefield. Hamas planned simultaneous attacks using low-cost rockets, commercially available drones, paragliders, bulldozers, trucks and even motorcycles to overwhelm the state-of-the-art ISR capabilities of the Israeli armed forces. The inference clearly is that Israel’s sophisticated Iron Dome system and its modern SAR (Synthetic Aperture Radar) capable Ofeq-13 observation satellite, multiple sensors, radars and air defence systems can be overwhelmed by an inundation of rockets. As part of its tactics, Hamas also effectively used multiple low-tech platforms to breach the security perimeter of Israel. Other takeaways from this conflict are the extensive use of tunnels to evade detection, store munitions and as bases for counter-attacks.

The Russia-Ukraine war has witnessed the use of cyber space to carry out Distributed Denial of Services (DDoS) attacks on the adversary’s critical infrastructure, including with the aid of non-state actors aligned with the establishment.

The Israel-Hamas conflict has also taken propaganda wars to an altogether new level. Civil society groups, particularly the youth as well as NGOs around the world, have developed new allegiances that often run counter to national positions. The exploitation of such sentiments is facilitated by social media platforms and deep fakes. One of the prominent examples during the Ukraine war was the AI-generated deepfake of President Zelensky surrendering to Putin. It was swiftly debunked by the Ukrainian government and news media, but yet succeeded in underscoring the future perils of deep fake technology riding the growth in AI.

Civil society groups, particularly the youth as well as NGOs around the world, have developed new allegiances that often run counter to national positions.

Yet another fascinating lesson from recent conflicts is the use of private internet systems and commercially available satellite imagery integrated with open-source information about troop movements and military build-ups. Ukraine used Elon Musk’s SpaceX Starlink satellite terminals as a digital lifeline for its soldiers and to mount attacks. For the first time in modern history, Big Tech owners like Musk are not only providing critical communications platforms to the military but also venturing to advise users about war tactics. The denial of such services by commercial vendors can impact the outcomes of wars. An example is the denial by Musk of the use of the Starlink network when Ukraine was planning to mount a surprise attack on Russian formations in Crimea.

The use of US-built Javelin anti-tank munitions by Ukraine against Russian tanks was one of the most explicit highlights of the conflict. A video shared on social media by Ukraine’s 36th Marine Brigade showed dramatic drone footage of Ukrainian soldiers firing the portable anti-tank FGM-148 systems with deadly effect on a Russian tank column. It sparked off a discourse about the impending obsolescence of tanks. Undoubtedly, every technological advancement on the battlefield elicits counter measures. New technologies emerge to negate the adversary’s advantage in a never-ending cycle of competition. In the case of the Javelin, not only is it expensive, but it also has long delivery schedules. Besides, the Russians seem to possess more tanks than the number of Javelins that can be deployed by Ukraine.

The technological tussle on the battlefield in Ukraine is breaking new ground such as the use of AI-based imaging and facial recognition software. The use of 3D printing of spares and their delivery to an immobilised tank on the battlefield using semi-autonomous delivery systems, as demonstrated by the US during Project Convergence 21 at the Yuma Proving Grounds in 2021, is also emerging as a factor in future wars.

Communication, encryption and decryption are also at the centre of tech wars. Ukraine is using commercial AI-enabled voice transcription and translation service to process intercepted Russian communications.

The technological tussle on the battlefield in Ukraine is breaking new ground such as the use of AI-based imaging and facial recognition software.

Natural language processing (NLP) translator capabilities in the hands of individual soldiers may become the norm in the future. Such capabilities also have the potential to emerge as a soldier support system that can help enhance direct communication and confidence-building measures across frontlines.

Modern wars do not always guarantee outright victories. The role of asymmetrical and disruptive tools and support of non-state actors often help to counter the most modern of technologies. At the same time, waging wars of attrition can be expensive. Western military powers have experienced an acute dwindling of their inventories of 155 mm artillery shells. As a result, their supplies fall short of the rate at which Ukraine is expending them.

This peculiarity of shortages in a conflict involving major powers and their allies has led to the emergence of new defence suppliers. For the western countries, the Republic of Korea (ROK) has emerged as a major supplier of artillery shells; Russia is sourcing Shahed-136 drones from Iran and artillery shells from North Korea.

Ukraine currently does not have an air force to match that of Russia and the latter has not fully deployed its own. Fulsome use of air power by either side might alter the course of the war, but could also draw NATO into the fray. The lesson here is that air power is often used selectively even in desperate situations, to avoid escalation.

Today, advanced space, cyber and AI technologies exist seamlessly with entrenched frontlines that echo the past. The difference is that the soldier in the trench is now an integral part of net-centric warfare.

Ambassador Sujan R. Chinoy is the Director General of the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (MP-IDSA), New Delhi