The South African MDPMI report is a step towards safeguarding media pluralism by regulating international digital platforms. This article explores major insights from the report and the role of transnational cooperation in holding digital platforms accountable to local laws.

Introduction

Australia’s ban on the use of social media by teenagers has caught the world’s attention. While controversial, the ban is the latest iteration of ongoing tensions between large technology firms and national governments. Recent years have witnessed increasing international scrutiny on Big Tech and social media platforms due to their influence on domestic political discourse and international relations. Over the past year, misalignment between private sector practices and public policy priorities has prompted legislative and administrative action requiring technology companies to align their operations and policies to national regulatory frameworks of the countries they operate in. Between 30 August 2024 and 8 October 2024, the Supreme Court of Brazil ordered a ban on Elon Musk’s social media platform X after the company declined to comply with a court order mandating the appointment of a legal representative in the country. In November 2024, the European Commission fined Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta EUR 797.72 million for breaching EU antitrust rules by linking its online classified ads platform (Facebook Marketplace) to its social media platforms and thereby “imposing unfair trading conditions” on other similar platforms. In the same month, the Competition Commission of India imposed a USD 24.7 million penalty on Meta for the roll out of WhatsApp’s 2021 privacy policy, which enabled the sharing of user information with other Meta-owned platforms like Instagram and Facebook. Underscoring the momentum for regulatory intervention of digital platforms in the Global South, the Market and Digital Platforms Market Inquiry (MDPMI) report released by the South Africa Competition Commission in November 2025 highlights the country’s position in this global regulatory discourse. The study was commissioned in recognition of how systemic network effects in digital platforms, the AdTech space dominated by tech giants like Google, and the emergence of generative AI (GenAI) services are disrupting local and indigenous news media systems by creating technical and financial constraints. This paper is part of a series that will analyses the findings and implications of the MDPMI report in the evolving online regulation landscape. As an introduction, this paper examines the major findings of the report and explores strategies to strengthen the resilience of local media ecosystems in countries historically positioned as consumer economies.

Recent years have witnessed increasing international scrutiny on Big Tech and social media platforms due to their influence on domestic political discourse and international relations.

Major Findings of the Report

In recent years, the South Africa government has transitioned from a hands-off approach towards digital platforms to one characterized by active legal and regulatory intervention. Similar to developments in India, the South African Information Regulator initiated a multi-year legal dispute with WhatsApp regarding its 2021 privacy policy update, requiring greater data transparency for domestic users under the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA) in 2025. Tensions with digital platforms were further heightened in relation to online content moderation due to the spread of misinformation during the 2024 elections in the country. In this context, the MDPMI report signals a push to hold global online platforms accountable to domestic judicial standards. Towards this objective, the report identifies the following disruptive dynamics in the South African media landscape:

Reduction in referral traffic: The report highlights the shift in global markets following the rise of social media. Digital platforms now function as intermediaries between publishers and audiences, with search engines and social media serving as primary gateways for news. In South Africa, Google Search accounts for 95 percent of the market share and is identified as the leading source of news according to surveys conducted for the MDPMI report. This dominance has compelled publishers to permit their content to be indexed in order to maintain public visibility. However, local publishers face challenges in monetising their online presence due to the prevalence of ‘zero-click’ searches, where users engage with content on social media without visiting the publisher’s website. The monopoly in online search also enables Google to channel traffic to its other platforms, such as YouTube, thereby reducing the amount of referral traffic to publishers.

Resource-constraints: The report highlights that financial pressures generated by the diversion of revenue away from print journalism is forcing cost-cutting measures in local news outlets. The closure of bureaus, contraction of newsrooms, and reduction in staff have contributed to the ‘juniorisation’ of journalism. Revenue decline coincides with rapid changes in global information ecosystems, shaped by algorithmic prioritisation of engagement metrics that favour sensationalism and outrage over objective and verified reporting. According to the report, the new media ecosystem imposes additional costs on journalism outlets by requiring investment in resources to counter misinformation.

Underscoring the momentum for regulatory intervention of digital platforms in the Global South, the Market and Digital Platforms Market Inquiry (MDPMI) report released by the South Africa Competition Commission in November 2025 highlights the country’s position in this global regulatory discourse.

Exposure to international competition: The report finds that social media and online platforms position local and vernacular news media at a disadvantage against international incumbents. Google maintains a monopoly in online search, and the report notes that international media and publishing houses are disproportionately represented in the ‘Top Stories’ section and in general search results, to the detriment of local or national South African media. As online traffic is diverted away from local publishers, the rise of GenAI has exacerbated the problem with AI chatbots scraping the web for data and grounding information without providing compensation to local platforms. Since most popular GenAI tools originate in a limited number of countries, the emerging digital landscape disproportionately extracts data and potential revenue from small and medium‑sized enterprises (SMEs) and publishers already operating under financial constraints.

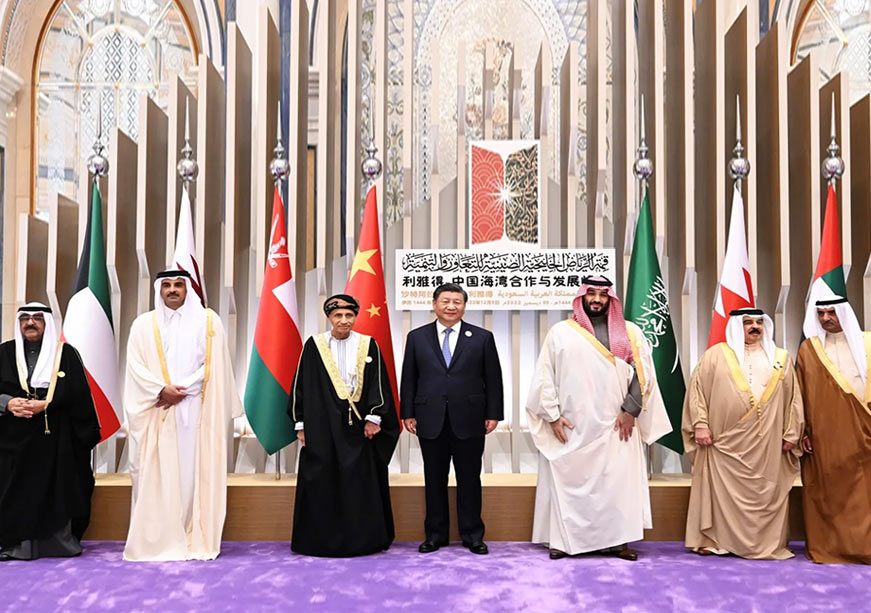

Taking a Bloc Approach

A persistent issue, the report mentions, is that local publishers lack bargaining power when negotiating with Big Tech companies. From the perspective of global search and information distribution platforms, “one media source is largely interchangeable with another when reporting on national events.” Given that South Africa has less monthly and daily active users (MAUs and DAUs) compared to larger user-bases in countries like India, Brazil or the EU, the incentive for online platforms to align with national priorities may not be sufficiently strong. A harmonised approach may therefore be necessary, given the number of commonalities in recent challenges to Big Tech platforms. The regulatory actions undertaken by Brazil, the EU and India converge with the anti-competitive practices identified in the MDPMI report, including abuse of dominance through self-preferencing, coercive ‘take-it-or-leave-it’terms and conditions, and evasion of local legal sovereignty. To galvanise the negotiating power of SMEs throughout Global South countries, adopting a bloc approach; whether through existing or newly established transnational platforms, may be necessary. Leveraging frameworks such as the BRICS Digital Economy Partnership Framework (DEPF), the Global Digital Compact (GDC) under the United Nations G77, and the ASEAN Digital Economy Framework Agreement (DEFA) to formulate bloc strategies and shared standards could strengthen the bargaining power of local publishers while simultaneously reducing compliance costs and regulatory uncertainty for Big Tech companies.

To galvanise the negotiating power of SMEs throughout Global South countries, adopting a bloc approach; whether through existing or newly established transnational platforms, may be necessary.

Going Forward

A long-term vision for addressing the aforementioned problems involves transforming cooperative mechanisms into enforcement-sharing blocs. For instance, geoeconomic groupings like the expanded BRICS can counter jurisdictional or regulatory evasion by introducing clauses in the DEPF where identification of abuse of dominance in one member state creates a presumption of dominance in others. While ASEAN’s DEFA currently focuses on trade facilitation in the region, it can be amended to prevent technology companies from relocating operations to jurisdictions with the most permissive laws through a nodal agency that conducts pan-regional algorithmic audits to detect algorithmic self-preferencing. At the UN level, the G77 bloc can take normative action to render extractive data practices diplomatically costly for technology companies. This could include defining AI model training based on local publishers’ data as a violation of national digital sovereignty, thereby granting smaller nations some command over their data. Furthermore, commitments can be outlined to designate major online platforms like X or Facebook as Essential Digital Public Infrastructure, discouraging them from including withdrawing services as a consequence of not accepting data and privacy policy changes to their products. Implementing such policy measures can leverage international cooperation to establish shared enforcement practices, thereby addressing the vulnerabilities of individual markets, contributing to a more inclusive and accountable digital future.

Siddharth Yadav is a Fellow with the Technology vertical at the ORF Middle East.