Contemporary conflict between State actors is increasingly unfolding in the grey-zone arena, an ambiguous space that lies below the threshold of declared war yet delivers strategic effects traditionally associated with kinetic campaigns. The epicentre of this alteration lies in the cyber domain, which has emerged not merely as an adjunct to military power but as a decisive battlespace in its own right. The pattern of growth is distinctive, cyber operations are used to weaken, confuse, or paralyse an adversary’s critical infrastructure even before conventional forces and tactics are employed.

Power grids, telecommunications networks, transport systems, and command-and-control architectures have become the first targets in what can be described as non-kinetic opening salvos of modern war. One such recent case is the January 2026 power grid failure in Venezuela, which was followed by the capture of its President, Nicolas Maduro, in Caracas by the US, an example of the use of the Grey-zone tactic in conflicts between State actors. US officials described the raid as the conclusion of months of covert surveillance, operational planning, and the use of cyber and electronic capabilities, which played a role in deactivating Venezuelan air defences and critical infrastructure before the kinetic attack.

This shift showcases a deeper strategic logic. Disabling electricity or communications does not incite the instant political costs of missile strikes, but it holds the power to cripple a state’s capability to govern, mobilise, or defend itself. In grey-zone rivalry, the aim is not sudden battlefield victory but strategic confusion, forcing the adversary into paralysis while sustaining plausible deniability. Cyber operations, therefore, serve as both a coercive instrument and a force multiplier for conventional military power.

US officials described the raid as the conclusion of months of covert surveillance, operational planning, and the use of cyber and electronic capabilities, which played a role in deactivating Venezuelan air defences and critical infrastructure before the kinetic attack.

The notion that cyber operations could serve as the “first strike” of a conflict is no longer theoretical. Over the past few years, several cases have established how cyber intrusions into critical infrastructure can shape the battlespace without triggering formal escalation. Attacks on power grids are the most potent target in this context. Electricity is the backbone of modern society; its disruption cascades across military readiness, economic activity, health care, public morale, and governance.

Unlike kinetic attacks, cyber operations can be pre-positioned years in advance. Malware may lie dormant within supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems, industrial control networks, or supply-chain hardware, awaiting activation at a politically or militarily opportune moment, such as the attack on the Ukrainian power grid in 2015-16. When triggered, such implants can produce effects that appear to be technical failures or natural outages, complicating attribution and delayed response. This combination of stealth, deniability, and strategic impact makes cyber operations an ideal instrument for grey-zone coercion.

Recent discourse around the US’ cyber operations targeting Venezuela’s power infrastructure has further sharpened global understanding of the integration of cyber and kinetic operations. While ground forces carried out the visible part of the operation, cyber operations created conditions that reduced resistance and reduced decision-making time for the Venezuelan military.

A cyber intrusion into the power grid forced military installations to switch to backup power. This transition typically introduces short but critical delays as systems reboot and stabilise, creating temporary blind spots or a ‘moss-window’ period in surveillance and air defence coverage.

In parallel, cyber operations targeted Venezuela’s air defence systems, including radar networks, focusing on intrusion in the software that processes radar data. This manipulation of the internal network system results not only in an apparent system failure but also in a misleading operational picture, which is often more dangerous because operators do not realise that they are compromised.

Equally important was the disruption of the communication network in the El Volcan area, including cyber interference with encrypted communications and the severing of key fibre-optic links, which can disrupt this command chain at critical moments. When communication fails, the command system also fails, thereby delaying defensive action.

Cyber operations targeted Venezuela’s air defence systems, including radar networks, focusing on intrusion in the software that processes radar data.

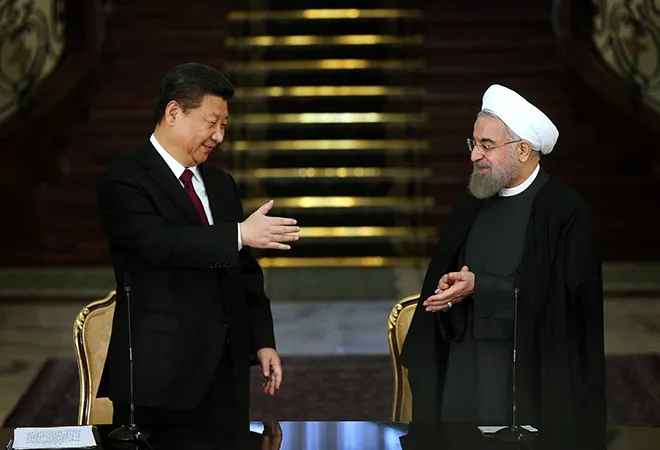

Another dimension of the operation appears to have involved the exploitation of surveillance infrastructure. Many States, including Venezuela, have invested heavily in “smart city” technologies such as networked cameras and biometric systems, often sourced from China, for example, from ZTE. These surveillance tools, designed for national security, can be repurposed as intelligence assets by an external actor.

Taken together, these measures establish a clear model of cyber–kinetic synchronisation. Cyber operations degraded power supply, distorted situational awareness, and paralysed decision-making, while conventional forces executed the final phase.

What is particularly enlightening is the stress on long-term preparation. Such operations require years of intelligence collection, supply-chain compromise, insider access, and dormant malware implants. This reinforces a central lesson for all States; cyber vulnerability is often embedded long before a crisis becomes visible.

India’s recent experience highlights both growing susceptibility and a degree of resilience in the face of cyber-enabled pressure. During the India–China standoff following the Galwan clash of 2020, Chinese intrusions into Indian power grid networks suggested an intent to signal access to critical infrastructure rather than to trigger immediate disruption. The subsequent Mumbai power outage (2020), attributed to a Chinese state-sponsored cyber intrusion, reinforced concerns about how civilian grids could be leveraged as strategic pressure points during geopolitical crises. At the same time, India managed to prevent escalation, restore services swiftly, and avoid systemic collapse, reflecting institutional coping capacity even amid uncertainty.

Looking ahead, the challenge is compounded by the prospect of China–Pakistan collusivity, where cyber operations against power, communications, or transport networks could be used to create friction and delay decision-making during a crisis without crossing the threshold of open conflict. These episodes reveal a persistent gap between India’s rising strategic exposure and its still-evolving cyber deterrence posture, even as crisis management and restraint have so far prevented grey zone actions from translating into broader instability.

Assessing India’s Preparedness: Structural Gaps and Strategic Blind Spots

India has made measurable progress in recognising cyber threats, yet significant vulnerabilities persist, particularly in the context of grey-zone warfare. Institutionally, cybersecurity remains disjointed across civilian, military, and sector-specific agencies. While entities such as the National Critical Information Infrastructure Protection Centre (NCIIPC) exist, coordination between central authorities, state governments, and private power operators remains uneven.

India has made measurable progress in recognising cyber threats, yet significant vulnerabilities persist, particularly in the context of grey-zone warfare.

A critical weakness lies in the civilian-military divide; power grids, ports, and telecommunications networks are largely civilian-owned and operated, yet their interruption has direct national security implications. Cyber defence exercises rarely simulate integrated cyber-kinetic scenarios that encompass extended pressure. This leaves India better prepared for isolated cyber incidents than for coordinated campaigns aligned with military escalation.

Another concern is supply-chain vulnerability, as much of India’s infrastructure relies on imported hardware and software, including components from suppliers in geopolitically sensitive regions. While awareness of supply-chain risks has grown, comprehensive auditing and diversification remain incomplete. As global experience demonstrates, compromised hardware does not announce itself during peacetime; its effects manifest only when activated.

India faces acute shortages of human capital and specialised expertise that bridges information technology and operational technology; cyber defence of industrial control systems requires a dedicated area. Training, retention, and integration of such knowledge into strategic planning remain inconsistent.

Furthermore, grey-zone’s cyber warfare exploits one of India’s most enduring strategic dilemmas of attribution. India’s declaratory posture on cyber retaliation remains underdeveloped. Without explicit signalling of red lines and proportional response mechanisms, adversaries may calculate that the benefits of cyber coercion outweigh the risks. Deterrence in cyberspace, unlike nuclear deterrence, depends as much on insight and credibility as on capability.

Addressing these challenges requires a conceptual shift. Cyber defence must be integrated into India’s broader military planning, rather than treated as a technical adjunct. Regular red-teaming of critical infrastructure, joint civilian-military exercises, and scenario planning for cyber-enabled grey zone conflict are essential.

Deterrence in cyberspace, unlike nuclear deterrence, depends as much on insight and credibility as on capability.

Equally important is strategic communication. India must demonstrate its capability to detect, attribute, and respond to cyber aggression. Deterrence does not require mirroring an adversary’s methods but convincing them that cyber coercion will enforce costs, whether through diplomatic, economic, or cyber means.

Grey-zone warfare has fundamentally altered the sequencing of the conflicts. Cyber operations targeting power grids and critical infrastructure are no longer secondary acts of espionage; they are emerging as the first blows in modern state-on-state confrontation. The experiences of India during tensions with China, the strategic logic illustrated by operations against Venezuela’s infrastructure, and the growing complexity of cyber-kinetic integration.

For India, the challenge is not merely technological but strategic. Without deeper integration, clearer doctrine, and stronger deterrence signalling, cyber vulnerabilities will continue to offer adversaries a low-risk, high-impact avenue for coercion. In the grey zone, the absence of preparation is a vulnerability itself, which can be exploited in the times to come.

This commentary originally appeared in Hindustan Times.