Ethical models for artificial intelligence are getting divided between Eastern and Western frameworks. India and the UAE are uniquely positioned to drive Eastern ethics in AI

Conversations about cooperation in Artificial Intelligence (AI) usually revolve around material engagement, using technology, collaborating on innovation and organising talent pipelines.

However, without an overarching ethical framework, the progress of AI is bound to be obtuse, perhaps even perilous. Concerns that ethical modelling in AI should not replicate the Anglocentrism of most of the world’s knowledge systems are leading to the bifurcation within the thinking on AI ethics between “Western” and “Eastern” models.

As AI becomes integral to our everyday lives, the question of how to infuse it with human values has become critical. Yet, “human values” are not monolithic. The global conversation on AI ethics has been largely dominated by Western perspectives, overlooking a rich tapestry of Eastern metaphysical traditions.

The global conversation on AI ethics has been largely dominated by Western perspectives, overlooking a rich tapestry of Eastern metaphysical traditions.

Eastern and Western models of AI ethics differ in profound ways in their attitudes on questions like “what is the nature of truth”, “what is more important–individual or societal well-being”, and “what kind of information should be curtailed or restrained for the common good”. While Western ethics in AI primarily arises from analytical rationalism and individual rights, Eastern ethics often prioritise holistic harmony, interconnectedness, and community responsibilities. Each shapes AI governance frameworks in distinctive directions.

Western vs Eastern Paradigm

Western philosophy roots its ethical discourse in dualistic models, materialism and the pursuit of individual rights, with foundational values such as privacy, utility, autonomy, and transparency at the core of its AI regulatory frameworks. The dominant Western paradigm, influenced by the Enlightenment and scientific empiricism, approaches AI through the lens of risk-based regulations that underscore functional capability assessments, rights-based protections, and utility maximisation. Questions such as “Does AI violate individual freedom?” or “How do we ensure fairness in automated decisions?” reflect this tradition.

Conversely, Eastern philosophical systems underline collective well-being, compassion and interdependence. In AI ethics, this translates into a focus on harmony, societal benefit, and ideas like a post-anthropocentric view of the use of technology that highlights empathy for all sentient beings.

This variance is revealed in practice. Eastern-inspired AI ethics treat digital minds, even hypothetical ones, as worthy of respect and ethical attention, with “sacred code[1]” approaches viewing the development of AI as a spiritual as well as a technical obligation. In the West, the emphasis on universal rules and rights, and utilitarianism, has led to an AI ethics focused on principles like individual privacy, autonomy and fairness. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, for instance, is a landmark regulation built on the sanctity of an individual’s data. In this view, a “good” AI respects personal freedoms, avoids discriminating against individuals and is transparent in its decision-making to ensure accountability. The United States (US) approach to algorithmic fairness and transparency is centred on protecting individual rights and reducing risks to consumers, favouring compliance, explainability and accountability. These frameworks, while pioneering global standards, sometimes face challenges adapting to contexts where community benefit outweighs individual utility.

The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, for instance, is a landmark regulation built on the sanctity of an individual’s data.

In the eastern framing, an AI is considered “ethical” if it enhances social cohesion, aids in collective development and operates with compassion. While this can be misinterpreted to justify intrusive surveillance, its core ideal is to use technology to foster a more interconnected and supportive society. The focus shifts from “what are the AI’s rules?” to “what is the AI’s role and responsibility within the community?”

India’s and the UAE’s approach

Eastern frameworks, especially in countries like India and the United Arab Emirates, emphasise inclusive development, balancing innovation with societal responsibilities, as well as broader notions such as human-centric AI and equitable technological access. Here, ethical frameworks are designed not only to mitigate risk but to actively promote social welfare, dignity, and human flourishing for the widest possible constituency. The difference between this and Western-style utilitarianism is two-fold. In the ‘Eastern’ version, the focus is far more on community needs than on individual rights, and there is a much greater focus on inner development and growth rather than an external, societal rules-based approach. The Eastern way highlights interconnectedness, the dissolution of ego boundaries, and the need to surrender to higher ethical and moral forces. In contrast, utilitarianism presumes stable agents making rational calculations to maximise collective utility.

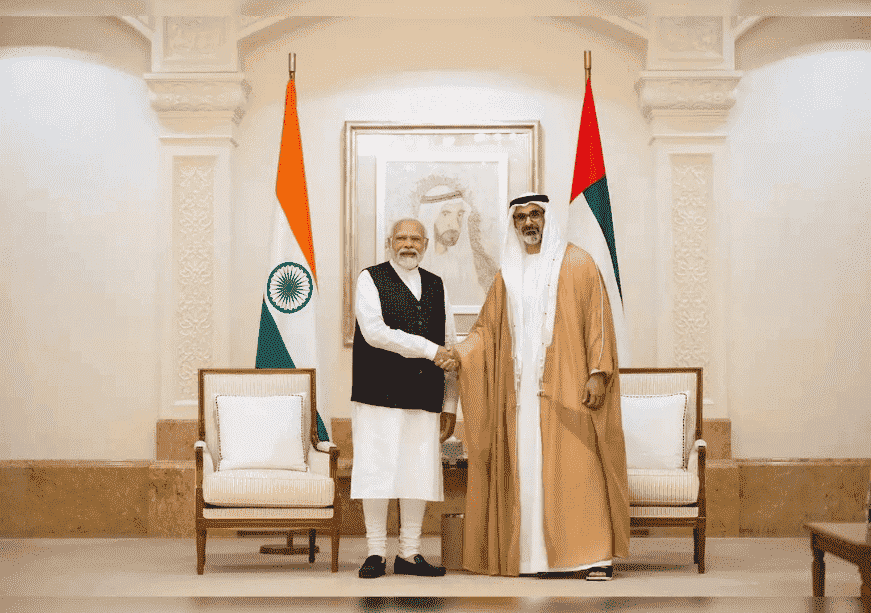

India and the UAE have been considered here because these two countries, while representing differing approaches to state and government structures, and shared disposition towards heightened security measures, have increasingly converged on outcomes of providing greater access to, utility from digital public goods for their citizens.

The Indian framework prioritises safety, reliability, privacy, accountability, and a thoughtful commitment to non-discrimination, positioning AI as a tool for public good secured in collective values rather than individual rights alone.

India’s approach to AI ethics is grounded in constitutional values of inclusivity, equality and societal advancement. “AI for All” is a guiding principle–one that insists technology serve even the most marginalised demographics, bridging digital divides and reinforcing positive human values throughout AI development. The Indian framework prioritises safety, reliability, privacy, accountability, and a thoughtful commitment to non-discrimination, positioning AI as a tool for public good secured in collective values rather than individual rights alone.

The UAE, meanwhile, balances rapid AI technological adoption with the development of standards of ethical governance that explicitly integrate Eastern values of harmony and interconnectedness. The country’s “AI Principles and Ethics” guidelines explain core values: fairness, accountability, transparency, explainability, resilience, safety, human dignity, and sustainability. The UAE treats these guidelines as a “living document”, meaning ethical standards continuously progress to address new challenges and civic needs while ensuring that all members of society, regardless of background, benefit. The UAE also links AI ethics with sustainability, establishing a strong connection between technology, environmental stewardship and long-term societal well-being.

The two countries already have an existing agreement to collaborate on the development and application of AI technologies in space, energy, healthcare and supply-chain sectors. However, they may have a more critical role in constructing eastern ethics for AI.

Ethics need to be practised, not just written. To promote the practicality of Eastern AI ethics, India and the UAE could take several steps.

One would be to draft an “Eastern AI Ethics Charter” that encompasses overarching principles and sector-specific regulations applicable regionally. For example, an AI system deployed for targeted government benefit distribution can be programmed not only for efficiency but also to ensure inclusivity and non-harm, prioritising the most vulnerable and avoiding bias. This means the AI is explicitly trained to detect and correct for historical biases (caste, gender, or rural/urban divides).

Another example could be: The AI flags a cluster of families as “high-risk for malnutrition” because it correlates low ration supplies with a recent failure of the local water pump. It then alerts the rural government social worker, not with a punitive “this person is at risk” message, but with a supportive one: “Community cluster ‘A’ may face nutritional challenges. Recommend prioritising visits and checking on ‘X’ and ‘Y’ supplies.”

The two countries could also act globally through promoting a pluralistic way of thinking in international forums and contributing to discussions on ethical governance at the UN, OECD, BRICS and the G20.

Another approach would be to work on co-piloted projects in the areas of health care and education to assess the feasibility of ethical frameworks. It would be important to invest in training for engineers, doctors, teachers and policymakers on algorithmic fairness, bias mitigation and ethical reasoning. The two countries could also act globally through promoting a pluralistic way of thinking in international forums and contributing to discussions on ethical governance at the UN, OECD, BRICS and the G20.

They could also move towards creating a new moral vocabulary for technology. The West has codified rules of rights and threats, while the East can develop ideas of principles for relations and responsibilities. India and the UAE can collaborate to create a new and culturally sensitive, internationally accepted system of ethics. Such a collaboration would be an example of ethical interoperability needed in the Global South.

This commentary originally appeared in Observer research Foundation.

[1] This simply means an approach to coding (or broadly technology creation) where the emphasis is not only on how efficiently the code or technology works but also ethical or moral aspects of what it does. So, as an example, not only how smoothly X or Instagram works, but also what these products do to human attention, and brains in what is increasingly called the ‘attention economy’.