It may be too early to call it a ‘Middle Eastern Quad’, but the United States, India, Israel and UAE are in for greater cooperation and coordination in the region

On 18 October, the foreign ministers of the United States, India, Israel, and UAE met virtually to enhance cooperation and partnerships between these states on the back of the Abraham Accords, signed in December 2020, normalising relations between Israel and a grouping of Arab states led by the UAE. While some have already christened this meet as a similar ‘design’ to that of the Quad, being built in the Indo-Pacific, the dynamics in West Asia (Middle East) are in fact much more complex for such a narrative to find space.

The US readout of the meeting highlighted trade, climate change, energy, maritime security as the core points of debate, along with generally expanding economic and political cooperation in the region. Meanwhile, India highlighted an “expeditious follow up” to this new ‘minilateral’, possibly hinting towards an institutionalisation of this dialogue process.

This “Indo-Abrahamic” construct, a term coined by scholar Mohammed Soliman, has great potential for expansive economic cooperation for all four members involved despite the challenges the region brings with itself, but perhaps more than anything else, solidifies a rapidly expanding India-US collaboration that today stretches from the Indo-Pacific to the Mediterranean and beyond.

External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar’s visit to Israel coincided with an Indian Air Force (IAF) contingent taking part in the Blue Flag 2021 military exercise. Interestingly, part of the IAF fleet and personnel arrived at Israel’s Ovda Air Force Base from Egypt, concluding exercises with the Egyptian armed forces. Both Egypt (along with Syria) and Israel fought the Yom Kippur War in 1973, and Israel’s Prime Minister Naftali Bennett last month visited the country for the first time in a decade, signalling another thawing of a major friction point in the region.

India’s diplomacy this past week in the Middle East, highlighted by a fast expansive military cooperation component as part of its outreach, has offered more political and diplomatic space for the balancing act it has had to orchestrate to protect its economic and political interests amidst the various fissures of the region over the decades, working with all three main centres of power in the region, the Sunni Arab camp led by UAE and Saudi Arabia, the Jewish power centre in Israel and the seat of power for Shia Islam in Iran.

This sense of diplomatic thaw in the wider Middle East region is not a one-off event today. While these overtures at play remain fluid and riddled with local political and societal complexities, efforts to try and bridge gaps led by regional actors themselves are pushed further by a spreading sense of the US turning into a recessionist power in the region.

While the long-term future of the American security umbrella was increasingly under scrutiny in the post-War on Terror era, an amalgamation of events over the years, ranging from the Arab Spring and Iran making significant strides in its nuclear programme to the likes of Saudi and UAE recalibrating their economy designs to adjust for future economic trends that move away from hydrocarbons, have pushed the three poles of power in the region to review their long-standing differences

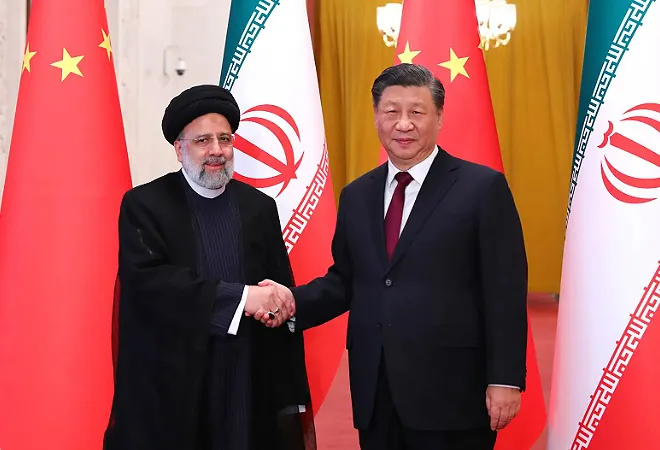

While the long-term future of the American security umbrella was increasingly under scrutiny in the post-War on Terror era, an amalgamation of events over the years, ranging from the Arab Spring and Iran making significant strides in its nuclear programme to the likes of Saudi and UAE recalibrating their economy designs to adjust for future economic trends that move away from hydrocarbons, have pushed the three poles of power in the region to review their long-standing differences. These shifts, along with the Abraham Accords, are highlighted by events such as Saudi-Iran talks in Baghdad, ending of the Qatar blockade and attempts to fix rifts within the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), UAE calling for ‘management’ of rivalries with Iran and Turkey and so on.

India has been relatively quick in taking advantage of these intricacies. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Israel in 2017, along with late president APJ Abdul Kalam’s visit to UAE in 2003 and Saudi King Abdullah Bin Abdul Aziz Al Saud’s visit to India in 2006, was one of the pivotal political moments for India in developing West Asia strategies over the past two decades. The momentum between the two regions and their strategic interests has only gone up. From the UAE providing mid-air refuelling to India’s new Dassault Rafale fighter aircraft on their delivery flight from France to a gambit of military exercises over the past two years despite challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic shows a sense of urgency from both regions to expand political and economic ties.

However, beyond the overtures mentioned above, the quick-paced collaborations in the region with Western states add a new dimension to India’s ‘Look West’ policy, which today stands out as an excellent Indian example of long-term diplomacy, stretching across party and government lines over the years. Strategically, the trade-offs between the Gulf nations and India on the fast-paced advancement of bilateral relations have been palpable.

For the Gulf, India continues to provide a significant market, including for hydrocarbons, despite the narratives of ‘energy transitions’ around the climate change debate. While the likes of Saudi Arabia try to end their economy’s almost exclusive dependency on oil, the Indian market and its growth projections are critical to Saudi’s economic transformation plans that also have a strong component of political transformation, moving towards a comparatively more inclusive and moderate form of Islam.

In the meantime, during these processes, India has also cemented itself as a growing political and security player in the region. From Operation Sankalp where Indian warships proactively escorted 16 Indian-flagged ships a day in and around the Persian Gulf as tensions between the US and Iran flared up to lesser-known tussles, such as those by intelligence agencies of India and Pakistan for greater clout in the UAE and the Gulf, and as per some accounts in recent times, India managing an upper hand, often forcing Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) to relocate capacity from the traditional stronghold of Dubai to Turkey.

Despite its indirect ways of addressing its core issue, the Quad is a construct designed and engaged around the rise of China in and around the South China Sea, and while Beijing is a growing player in the Middle East as well, conflating the two issues, geographies, and polities, even though a wider lens of how to deal with a rising China, is a fundamentally flawed approach

Finally, while opportunities abound around these new political designs in the Middle East, equating such minilaterals to the much-debated and celebrated ‘Quad’ infrastructure in the Indo-Pacific is a misnomer. Despite its indirect ways of addressing its core issue, the Quad is a construct designed and engaged around the rise of China in and around the South China Sea, and while Beijing is a growing player in the Middle East as well, conflating the two issues, geographies, and polities, even though a wider lens of how to deal with a rising China, is a fundamentally flawed approach.

The Middle East, despite the Abraham Accords, is a more-than-often volatile region in transition, and what lies on the other side is largely unknown. However, the positive here is that whatever the outcome, it will now be largely driven by the Middle East States themselves.

This commentary originally appeared in First Post.