The 11th India–Japan Energy Dialogue and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Tokyo in August put energy at center stage, with critical minerals as one of the key aspects of economic strategies.

At the end of August, India’s Ministry of External Affairs released a Fact Sheet on India–Japan Economic Security Cooperation, identifying semiconductors, critical minerals and clean energy, etc, as priority sectors for collaboration. Both governments pledged support for private sector–led initiatives and emphasized cooperation through multilateral frameworks such as the Mineral Security Partnership, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, and Quad Critical Minerals Initiatives.

Concrete measures have been taken in this direction, like India’s Ministry of Mines and METI signed a Memorandum of Cooperation in August, while Toyota Tsusho expanded its rare earths refining project in Andhra Pradesh, India to set up a stable supply chain. Meanwhile, initiatives like the battery supply chain roundtable organized by JETRO in India signal appetite for further cross-border links.

Yet despite this momentum, much of the agenda still consists of frameworks, dialogues, and memoranda rather than large-scale projects. This “pending promises” gap is striking, particularly given Japan’s own track record of building durable supply chain architecture in response to past crises (see author’s analysis in Japan NRG, June 2, 2025), and India’s rising urgency to reduce its critical mineral dependencies.

While opportunities span joint exploration, refining, recycling, and technology collaboration, persistent challenges of policy execution, infrastructure, and investor confidence continue to weigh on delivery. Whether Tokyo and New Delhi can now translate complementary strengths into concrete outcomes will determine whether critical minerals become a genuine pillar of their partnership, or remain aspirational.

Diplomacy and Ambitions

Japan’s resource security architecture has been steadily reinforced over the past two decades through institutional and legal innovation. The Supply Chain Diversification Programme, launched in 2020 with a budget of $2 billion, was an early step, providing subsidies for Japanese firms to relocate production out of China, initially to ASEAN, and later to India and Bangladesh under its expanded second phase.

The Economic Security Promotion Act (2022) gave this approach a statutory backbone, mandating supply chain risk assessments for strategic goods. It established a new system of subsidies and insurance for companies, and enhanced public–private coordination across critical sectors such as minerals, semiconductors, and energy.

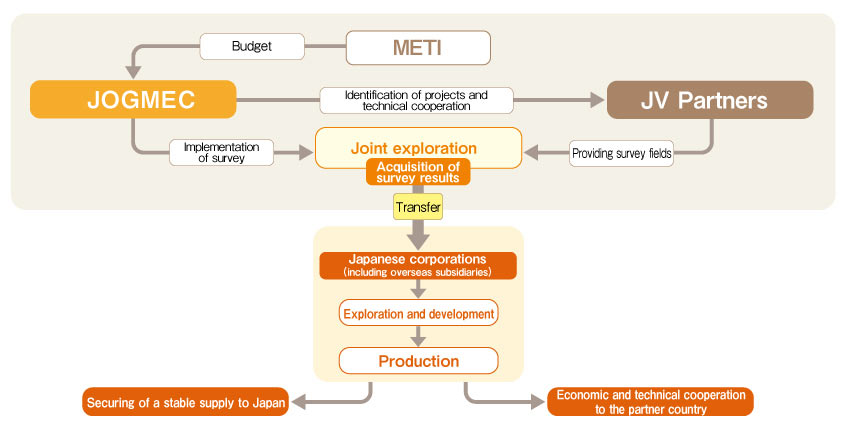

Flow of JV survey implementation system

Source: JOGMEC

The result is a distinctive playbook that combines financial incentives, statutory authority, and institutional depth to build supply chain resilience. Despite gaps, these tools provide Tokyo with a relatively well-developed framework to confront today’s fractured geopolitics.

On the other hand, India has entered the critical minerals race with growing urgency. According to the Ministry of Mines, India met 80% of its lithium and cobalt requirements and 90% of its rare earth element demand through imports in 2023, underlining its dependence on external supply. The launch of the National Critical Minerals Mission (NCMM) in January 2025 signalled a strategic shift, from being primarily a consumer to an ecosystem builder across exploration, processing, and recycling.

Components of NCMM

Source: Pres Information Bureau, Government of India

The scale of India’s dependency is stark. Imports from China surged dramatically in recent years; lithium by 921% and nickel by 137% in 2024 and graphite by 85% between 2022–24 . This rising reliance has sharpened the policy push to diversify. Early-stage deals have been pursued with Zambia, Mongolia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, while domestic players are being encouraged to accelerate exploration.

Institutional mechanisms have also expanded. Khanij Bidesh India has been tasked with overseas acquisitions, while Indian Rare Earths Limited and private explorers are mobilized to strengthen refining and recycling capacity. The NCMM is designed to coordinate these efforts under a single umbrella.

There is a reason for India to dig locally. India holds 6.3% of global rare earth reserves, with deposits including neodymium and praseodymium. In 2023, significant lithium reserves were identified in Jammu and Kashmir, though exploration remains at an early stage. India is also in the top five producers of natural graphite, with 3.1% of global reserves and growing capability in producing spherical graphite for EV batteries.

However, critical mineral auctions have struggled to draw investor interest, due to unclear reserve data, concerns over mining capabilities, and inadequate technology.

In refining, however, India is beginning to scale. The International Energy Agency projects its global share of refined copper capacity will rise from 2.1% in 2023 to 3.5% by 2035. This aligns with India’s ambition to become not only a major consumer but also a processing hub within critical mineral value chains.

From dialogue to delivery

India and Japan have the foundations for deeper critical minerals cooperation, but the real test lies in whether these frameworks can translate into bankable projects.

A flagship example is Toyota Tsusho’s rare earth venture in Andhra Pradesh, launched with Indian Rare Earths in 2012 and now run through its subsidiary, Toyotsu Rare Earths India, has become a critical supply chain node. The facility processes thousands of tons of rare earth oxides for export to Japan, proving that joint projects can move from MoU to market.

Indian industrial groups such as JSW, Vedanta, and Adani are also reportedly exploring partnerships with Japanese firms on battery technologies and minerals projects.

Beyond individual ventures, the two countries share a converging outlook. Their official lists of critical minerals overlap and this provides a clear platform for scaling cooperation into practical, investor-ready ventures.

Further pathways for collaboration include:

- Joint Exploration & JVs: India allows 100% FDI under the automatic route for mining and exploration of metal and non-metal ores, which opens the door for Japanese capital and technology to participate directly in local exploration. Further, Japan and India (e.g. via JOGMEC + KABIL) could undertake JV exploration in other countries based on Japanese expertise in such ventures.

- Processing & Refining Close to Market: Japanese investment in Indian refining (for example, rare earth oxides or magnets) could fast-track supply chain integration, with lower environmental clearance and less capital risk. For example, both countries already have footholds in the copper supply chain. Japan is the third-largest refiner by company ownership and the fifth by location, while India is bringing new capacity online.

- Recycling / Urban Mining: The India–Japan Clean Energy Partnership, signed in 2022, names recycling as a candidate for future collaboration. Expanding capacities for recycling of e-waste and end-of-life batteries in India, using Japanese recycling technology, could reduce import dependence and improve environmental outcomes.

- Regulatory Incentives & Project Support: India eliminated customs duties on 25 minerals, reduced Basic Customs Duties (BCD) on others, accelerated environmental and mining clearances, and introduced financial incentives for exploration.

- Human Capital, Standards & Agile Pipelines: Scaling of refining, recycling, and processing will require investment in training and ESG standards.

Together, these initiatives would not only bolster supply chain resilience but also offer a portfolio of investable opportunities. For Japanese firms, India provides scale, growth, and market proximity; for Indian stakeholders, Japan offers technology, financing, and credibility in global markets. For global investors, their convergence is a hedge against geopolitical risk.

Pending promises: Gaps in delivery

Progress on critical minerals has been limited compared to Japan’s strides with partners like Australia, Chile, or France. India–Japan initiatives remain disproportionately heavy on paper promises and discussions.

Meanwhile, the JBIC’s 2024 survey reaffirmed India as the most promising long-term destination for Japanese firms, while also revealing declining business planning ratios. Many companies remain cautious, citing policy uncertainty, legal complexity, infrastructure bottlenecks, and execution risks.

This gap underscores the broader problem: India–Japan critical minerals cooperation has momentum in vision but remains patchy in delivery. For now, the partnership risks lagging behind the pace of both market demand and competitor alliances. Without credible midstream and downstream infrastructure, even expanded exploration risks stalling at the mine gate.

Both need to proceed to co-financed mines, processing hubs, and recycling plants. For India, this means mobilising Japanese capital and technology to unlock its resource potential. For Japan, the upside is securing resilient access at a time when diversification is no longer optional but essential.

Conclusion

As global competition over critical minerals intensifies, the risks of autarky and fragmented supply chains are becoming clearer. If markets segment along geopolitical lines, prices will rise, volatility will increase, and supply shocks will ripple more widely. Neither India, Japan, nor even China benefits from such an outcome.

What is needed instead are transparent international markets where rules and standards encourage open flows, while balancing national security concerns. Especially so because demand and technological shifts constantly reshape which minerals are “critical.”

India and Japan are well placed to build on their complementarities. Japan brings capital, technology, and institutional depth in refining, recycling, and standards-setting; India offers scale, a growing manufacturing base, and untapped reserves. Together they cover significant ground across copper, graphite, rare earths, and lithium; minerals central to electric vehicles, semiconductors, and renewable energy.

Institutional frameworks are already in place. These initiatives provide scaffolding for long-term cooperation, but credibility will depend on whether the two sides can move quickly from frameworks to deliverable projects that attract investors.

This commentary originally appeared in Japan NRG.