The collapse of Assad’s Syrian government and the broader shift in the Middle East is going to have a rupturing effect if the regional problems do not find regional solutions

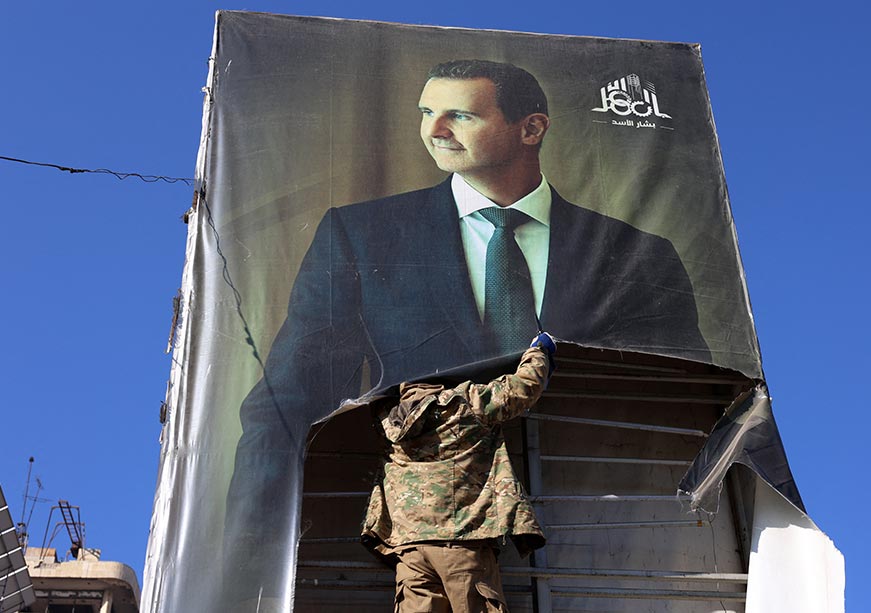

The Syrian civil war, in hibernation for many years, has come back with gusto as the long-standing government of Bashar al-Assad collapsed in an undramatic fashion. This ended the 60-year reign of the Assad family and the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party which took power following the 1963 military coup. A coalition of rebel militias, spearheaded by Hayat Tahrir al–Sham (HTS)—an offshoot of Al Qaeda, led by 42-year-old Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, remains at the forefront of governing the current juggernaut. The country’s armed forces have seemingly disintegrated, capitulated, or simply switched sides.

HTS has, ironically, conducted a shock-and-awe offensive of its own. The Syrian crisis has been rankled loose by regional instability over the past year, starting with the terror attack by Hamas against Israel in October 2023 and the subsequent geopolitical consequences in Gaza, Yemen, Lebanon, and Iran. The Syrian war never really went away, it was brushed under the carpet, managed, and even forgotten. Regionally, however, it has always been a potpourri of tussles between local groups and foreign powers, particularly between the Arab states, Türkiye, Iran, Israel, the United States (US), and Russia.

In essence, the conflict from 2011 onwards can be contextualised through three main strategic views: domestic, regional, and international.

Domestic

HTS and its figurehead Jolani have been taking on Assad’s forces in a gambit of cities across Syria over the past few weeks. In the past years, HTS produced a quasi-state with its own governance structure, taxation and revenue system, and healthcare. HTS is, of course, not the first group to fine-tune this model. Al-Shabaab in Somalia has mobilised similar strategies for some time now. The Taliban in Afghanistan has continued to do so since 2021 as the only formal political power in the country. Furthermore, Jolani himself has also stated that he has no interest in furthering sectarian or ethnic fault lines while simultaneously hinting towards the establishment of an ‘Islamic government’. He has advised his followers not to damage surviving public institutions (hospitals, healthcare, and police, among others).

However, the HTS and various other rebel militias, including the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) lead euphoric scenes on the streets of Syrian cities, highlighting the mounting pressure against the former state’s regressive system. Reports of the army’s widespread abandonment of military positions sheds light on the tactical, strategic, and moral depletion of the security architecture which the Russians were supposed to help rebuild. On the other hand, the HTS was much better prepared, using military academies, hybrid weapons, and formalised command and control structures, built with the help of former generals and commanders who previously worked under Assad.

The future of Syria’s political order is up in the air. The country’s dire economic situation has been pushed further into an abyss. If the HTS stakes claim, Jolani could be well on his way to becoming the next theocrat, opening a new chapter of uncertainty to a region that is already ablaze. The Syrian Prime Minister Mohammad Ghazi al-Jalali’s call to have free and fair elections, while also facing the reality of having to hand over the city’s keys to Jolani could fracture internal views on how the country should proceed. While Jolani is unlikely to agree, if others such as the SDF give the idea of elections momentum, it could be seen as an opening by both regional and Western powers to influence impending outcomes.

Regional

Since the civil war started, Iran has played a critical role in making sure that Damascus remains close to Tehran. Over the years, Syria became ground zero for Iran-backed proxies while acting as a weapons trade route to arm Hezbollah in Lebanon. The former Iranian military general, Qasem Soleimani, who was assassinated in Baghdad by a US drone strike in 2020, was widely known to be the chief architect of this setup.

Assad himself was unpopular amongst most of the neighbouring countries. While his subservience to Iran (and Russia) in return for a retention of power was seen as problematic, a slow return to the Arab fold had been underway since 2023. In November 2011, Syria was suspended from the Arab League for being unable and unwilling to stop violence against protesters. For Arab states, support for the anti-Assad movement in its initial years became unavoidable as the country’s Sunni Arab majority resisted the decades-long rule by the Assad family, which belonged to the Alawite minority—an ethno-religious group practising a branch of Shia Islam.

Now, with Assad seemingly destined for the annals of history, Jolani presents a big challenge. In his speeches, the HTS leader has said that he wants to put an end to Iran and Russia’s interventions. While all these overtures are strategically palatable to Arab capitals and Israel alike, his ideological opposition to what they have sided with remains a core challenge. Arab powers such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia have actively undermined the Muslim Brotherhood and its ecosystems across the Middle East, while Israel continues its fight against Hamas, which emerged from the Sheikh Ahmed Yassin-led Mujama al-Islamiya, a charity affiliated with the Brotherhood working in the West Bank and Gaza. In the long term, Jolani’s candidature as the head of Syria will be an uncomfortable reality for almost everyone, albeit for diverse reasons.

Nevertheless, regional management via power rivalries is already underway. Russia, Türkiye, and Iran recently met in Qatar to discuss the developments in Syria where all three states have overlapping interests through various groups. Ankara, for example, has supported and honed the Syrian National Army, a coalition of anti-Assad organisations. Previously, Israel and Russia maintained a line of communication over the former’s airstrikes inside Syria targeting Iran-backed proxies. With a minefield of groups and interests at play, mistakes by anyone could have consequences for many.

Global

If Syria does come under HTS rule, it will be the second state after Afghanistan to have had a successful militant takeover, an indictment of the two-decade-long ‘War on Terror’. Jolani, much like Sirajuddin Haqqani, the Taliban interim government’s Interior Minister in Kabul, continues to have a US$10 million bounty on his head by the United States (US). Both have appeared on Western media off late, giving interviews as individuals in positions of power.

The impact that the Taliban’s victory in Afghanistan has had on Islamist groups cannot be understated. In 2021, HTS-held territories such as Idlib congratulated the Taliban through prayers aired across the geography on loudspeakers from mosques. During the same period, HTS ideologue Abd al-Rahim ‘Atun gave a lecture on “the Taliban as a model”. Their victory was seen as an aspirational blueprint for others. If the US can be defeated, then the likes of Assad can certainly be removed. The Taliban itself has congratulated the HTS and offered guidance on the path forward.

Russia and Iran’s role in Assad’s survivability, cannot be understated. In 2015, Damascus invited Moscow to intervene in the country’s battle with the so-called Islamic State (also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and ash-Sham (ISIS) or Daesh in Arabic). Though Moscow’s support was existential, it arguably has changed since the war in Ukraine, where Russian military and economic capacities have been bogged down. While Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said that Syria cannot be allowed to fall into the hands of terror groups, he offered little to no practical support to Assad, much like Iran. That said, Russia’s intervention could still have a second play, as it would look to maintain its air and naval bases in the country’s Tartus and Latakia governorates—Moscow’s only remaining tactical presence in both the Middle East and the Mediterranean.

Beyond the above-mentioned intricacies, a Jolani-led Syria would be one more blow to global counter-terrorist ambitions. With Somalia, Afghanistan, Yemen, and now potentially Syria as success stories, Islamist militant groups, specifically in the African Sahel, might feel emboldened to try and take over the slew of fragile states in West Africa. All these realities stand tall as the consequence of both global security failures and symptoms of American recidivism from actively playing the role of global policeman. The latter is further highlighted by incoming president Donald Trump’s statement saying that the US should not intervene.

Conclusion

Whether it is Syria, Yemen, or the crisis in Gaza and Lebanon, the envisioned ‘new’ Middle East is at odds with the ‘old’. The current events are not sudden, but a symptom of the past decade, with an undercurrent of the Arab Spring era. Beyond the country’s own fate, a churn in both regional and international geopolitics is going to have a rupturing effect if the regional problems do not find regional solutions. The potential nuclearisation of the Middle East also remains an international worry. What happens in Syria going forward will have an impact much beyond the region, as its new political reality unfolds in the coming months.

Kabir Taneja is Deputy Director of the Strategic Studies programme at the Observer Research Foundation