In 2022, the Global Food Security Index ranked all Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states in the Top 50 most food-secure states in the world. Interestingly, all the GCC countries ranked even higher than India and Brazil, one of the largest food producers in the world. Despite achieving a high degree of food security, for a region that imports 85 percent of its food, the issue continues to hold relevance. This was underscored in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) Food Security Minister, Mariam Hareb Almheiri’s statement, “[a]s food security is a pressing resource security challenge for the UAE, we have a keen interest in increasing agricultural efficiency through the adoption of new methods and diversifying the pattern of agricultural investment abroad (…) to support sustainable development and bridge the nutritional gap”. While bilateral trade between Africa-GCC and South Asia-GCC has furthered the food security agenda, a tripartite partnership between South Asia, Gulf and Africa might be the “diversification of agricultural investment abroad” that is needed. This article aims to understand the current status of food security partnerships and advocate for a comprehensive food corridor across the three regions.

Trade partnerships in South Asia vs direct investments in Africa

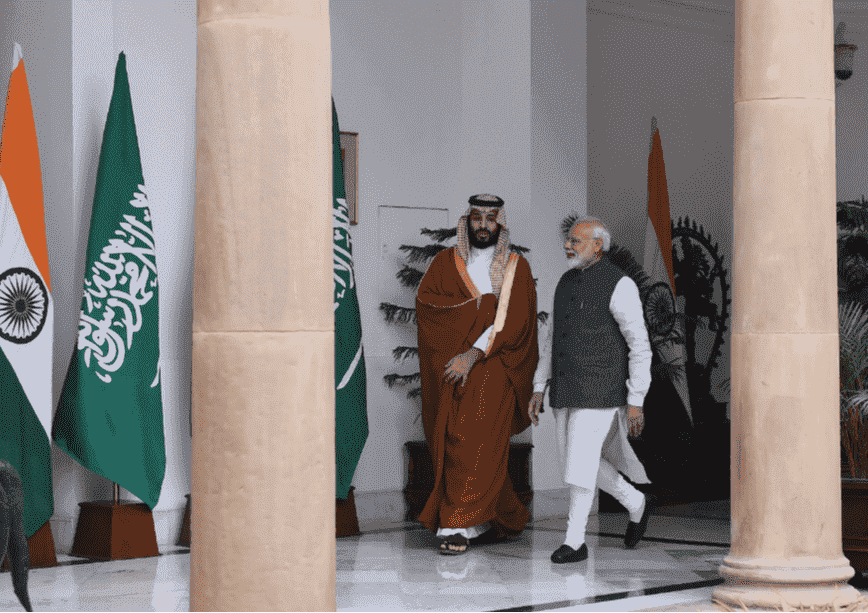

GCC food imports in 2022 stood at 34.15 million MT, with Saudi Arabia and UAE accounting for about 80% of the total regional agricultural imports. South Asia (particularly India) dominates the food exports to GCC. This food trade is facilitated by structured trade partnerships, which focus on market access. For example, in 2022 the UAE and India agreed to a US$ 7 billion food security corridor during the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), connecting Indian farms directly to the UAE ports, and food trade between the two nations soared. Similar partnerships can be seen through the South Asia-GCC belt with Pakistan signing a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with GCC with a focus on food imports. These partnerships leverage South Asia’s established agricultural systems and supply chains. High-yield crop varieties and refined farming techniques used in South Asia, along with their expertise in effective pest management and cold chain logistics, help efficiently produce and transport food to the GCC. Thus, while engaging with South Asia, GCC is an importer of food that utilises existing farming systems.

In contrast, GCC is more closely involved in food production and transportation in Africa. This was highlighted by a property valuer of farms, “[t]hey [GCC countries] want to produce it here, take it to the Gulf, and then store it for twenty years or more to boost food security,”. As a result, GCC has enhanced their food security by direct land acquisitions in Africa which homes 60 percent of the world’s uncultivated arable land. Food demand in the Arabian Gulf varies widely, with the UAE ($39 billion) and Saudi Arabia (US$20 billion) agricultural imports from Africa valuing far more than countries like Qatar (US$1.5 billion) and Oman (US$667 million).

This is reflected in the extent of investments GCC countries have in Africa. Saudi Arabia and the UAE have substantially more tracts of land investments. Hence, neither the GCC nor Africa are monolithic. While UAE, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Kuwait all hold large farmlands in Sudan, Kenya and Tanzania receive greater agricultural investments from Qatar and Saudi Arabia respectively. These lands are used to grow crops like cereals and fruits, which are tailored to GCC dietary needs. Take, for example, Saudi Star which developed a rice farm of 15,000 hectares in Ethiopia, with plans to cultivate an area of up to 500,000 hectares. While cultivating these lands, GCC countries have introduced modern agriculture techniques to increase crop yield. Additionally, GCC nations often develop agricultural support infrastructure like irrigation systems and ports that strengthen supply chains. The Qatar Fund for Development funds solar-powered irrigation facilities in Senegal, while DP World operates ports and logistics centres in nine African countries. These investments also extend to agro-processing units in Africa, enabling the production of value-added products that meet GCC needs before export.

Therefore, in South Asia, the emphasis is on improving market access and utilising existing agricultural systems while GCC directly invests in African agriculture to build infrastructure from scratch. This approach leverages the unique strengths of these regions: the mature food production industry in South Asia and vast arable land in Africa.

Triangularisation across South Asia-Gulf-Africa

The GCC approach to food security in South Asia and Africa hints at opportunities for triangulation: symbiotic collaboration between South Asia, the GCC and Africa to combine their respective strengths for mutual benefit. South Asia contributes advanced agricultural expertise, the GCC provides financial resources, and Africa offers vast untapped arable land.

South Asia’s technological advancements in agriculture like crop management software and genetically enhanced seeds, offer solutions to the persistent productivity lag in African agriculture. A study by the Atlantic Council, suggests that replicating the productivity boosts achieved during India’s 1960s Green Revolution alone could add $200 billion to Africa’s economy by 2030. This study also reports that the Indian agricultural sector shares challenges with Africa, like climate change and limited mechanisation. Hence, solutions that have proven useful in South Asia could help Africa.

As a result, South Asian agri-tech firms could improve yields on GCC-funded farms in Africa. Such partnerships will also address the escalating threats of climate change which increasingly risks rendering lands marginal. The importance of such collaborations was also echoed by Dr Ismahane Elouafi of the International Center for Biosaline Agriculture (ICBA), “[r]esources are the most vulnerable to climate change, so we have to protect them, address the challenges facing people in marginal environments, and diversify crops. But we can only do that through partnership. We need to plan and act together.”

Support for similar South-South collaborations has been increasing with the United Nations Capital Development Fund working to extend India’s agricultural technologies to Asia and Africa. However, these partnerships are limited and centred on India-Africa. Expansion of these partnerships could help other South Asian countries, particularly stronger agricultural economies like Pakistan and Bangladesh, access new markets.

Triangulation of these regions holds important benefits for all. For South Asia, this partnership opens new markets for scaling agricultural innovations and boosting export-driven growth, expanding the existing collaborations. For example, 100,000 Indian Kirloskar pump sets are working along the Nile River to green the desert lands in Egypt. Despite the desirability of these partnerships, challenges remain as highlighted by Felix Matati, Minister for Commerce, Trade and Industry, Zambia, “[A]frican countries would prefer Indian investment as we understand each other. You have cost-effective technology, which we want. We can understand each other better as we are both from the south. India-Africa trade has been lacking clear visibility. We want to change that”. A lack of structural trade engagements between the two regions and Africa’s infrastructure deficits hinder trade efficiency. These are the exact gaps that the GCC countries are equipped to address and promote tripartite partnerships, given their heavy investments in African infrastructure and farmland.

The Gulf can both facilitate these partnerships and benefit from them. This boosts GCC food security by enhancing land productivity and securing a stake in emerging agri-tech. Fostering economic stability in Africa and South Asia also helps the GCC gain stable trading partners and geopolitical relevance. Beyond food security, these partnerships build on GCC’s existing ambitions, especially of UAE and Saudi Arabia, to become a global logistics hub.

Africa also gains from the resultant accelerated agricultural development without the hefty R&D investments typically required for such advancements. The infusion of proven practices from South Asia, supported by GCC capital, can help Africa overcome longstanding productivity challenges and improve growth. While these technologies might be first adopted on GCC-supported farmlands, they will have important spillover benefits through knowledge transfer among the local populations.

Four pillars enabling triangulation of agricultural trade

While the benefits of this triangulation are evident, it is important to define the pillars that can enable such a tripartite partnership. There are four essential pillars: GCC-led negotiations, structured trade partnerships, integration with existing trade frameworks and private sector involvement in food trade. These pillars will not work in isolation but collaborate to strengthen the triangulation approach.

Building on the first pillar, GCC leadership will be pivotal in facilitating negotiations between South Asia and Africa to establish comprehensive FTAs that create a seamless food security corridor across the three regions. To strengthen the second pillar of structured partnerships, these FTAs should go beyond tariff reductions to include technology transfer, infrastructure development, and sustainability goals. Further, a successful model of triangulation will utilise the third pillar of existing trade agreements, such as the India-UAE CEPA and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). The CEPA’s success in reducing tariffs and streamlining food supply chains can be expanded to include African nations, leveraging Gulf investments in agriculture. Similarly, the AfCFTA, which harmonises trade policies across 54 African nations, provides a framework for eliminating barriers and fostering intra-African trade. By aligning Gulf-backed infrastructure investments with AfCFTA goals, agricultural goods and expertise can move seamlessly across borders. Integrating these agreements under a unified strategy will allow South Asia’s agri-tech innovations to enhance productivity on African farms supported by GCC investments.

For the success of any such trade policy, the final pillar of private sector adoption is crucial. These agreements must be developed in consultation with leading private sector players, particularly Food Tech companies in South Asia, such as Ninjacart and DeHaat, which are revolutionising agri-supply chains. GCC-based firms like Agthia and Al Dahra, which focus on food production and distribution can provide insights on the current trade gaps and solutions. African players like The African Plantation Company can help understand and bridge on-ground implementation needs. Such collaborations will align trade agreements with market needs and encourage private sector presence in the emerging food security corridor.

In conclusion, each region can contribute to and gain from this tripartite partnership. South Asia offers agricultural technologies, Africa provides arable land, and the GCC supplies financial investments. Further, South Asia can access new markets, Africa can achieve economic growth through improved agricultural productivity and the GCC can enhance food security. Thus, triangulation through structured trade agreements can enable these regions to address their unique gaps by building on their respective strengths.

Samriddhi Vij is a Research Assistant at ORF Middle East.