As India looks past its 76 glorious years, it is prudent to chart the country’s next major developmental milestone: mapping the 5 trillion-dollar economy. At the current GDP, it would take five years to achieve the goal pegging the nominal growth rate at 10 percent. Islamic Finance (IF) could play a potential harbinger in fast-tracking the developmental agenda by contributing 700 billion (14 percent) over the next five years. Taken together, IF commanded assets under management (AUM) currently at US$ 3.95 trillion projected to touch 5.9 trillion by 2026. Opening India’s banking and financial sector to IF presents an opportunity to capture at least 14 percent of the market share, providing opportunities for India’s Muslim population (representing 14 percent) to fully integrate into the formal financial system. Considered as an alternative finance vehicle, IF currently constitutes US$ 3.5 trillion making up less than 5 percent of the world economy with emerging markets serving as the primary recipients. Among them, the Middle East and South-East Asian (part of ASEAN) nations command the bulk of the share with most of them being one of India’s major trading partners. Interestingly, all the member nations of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (excluding India) have embraced IF at varying degrees. Russian Federation is actively mulling IF to meet its financing goals, particularly in the regions dominated by the Muslim population.

Islamic Finance (IF) could play a potential harbinger in fast-tracking the developmental agenda by contributing 700 billion (14 percent) over the next five years. Taken together, IF commanded assets under management (AUM) currently at US$ 3.95 trillion projected to touch 5.9 trillion by 2026.

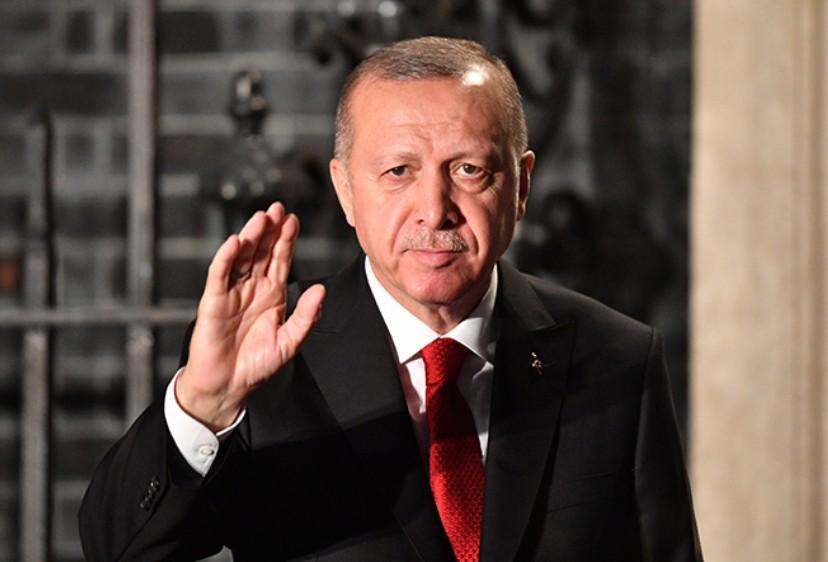

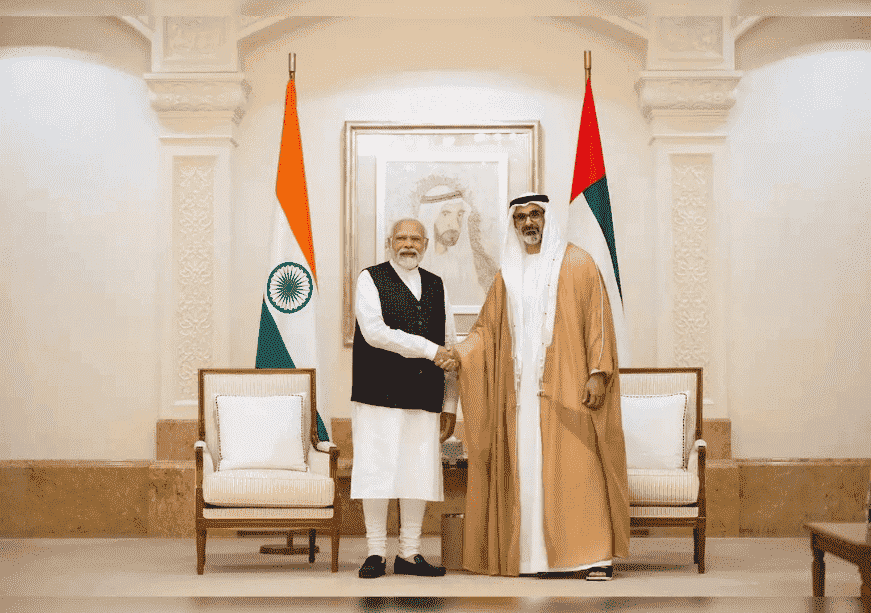

In light of the strategic relationship between India and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) culminating in the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) deal with bilateral trade already surpassing the US$50.5 billion mark in June 2023, IF offers an alternative finance vehicle providing impetus in the trade finance arena. With IF hinging on the Sharia covenants with total assets accounting for 30 percent of the financial system in the UAE, India, as one of the largest unpenetrated markets, could potentially leverage these learnings with scalable benefits in boosting trade opportunities.

From an asset-finance perspective, Murabaha or cost-plus-profit contract stands out as the preeminent contract generating 80 percent of the revenues in Islamic Banking. The bank essentially acts as an intermediary between the vendor and buyer by leasing the asset to the lessee for a series of payments covering both cost and profit. The bank as a lessor transfers the legal ownership to the lessee (buyer) upon receiving all the payments. In principle, as legal custodian of the asset until completion of payments, as an asset owner, the bank is relatively well-insulated from potential delinquencies in contrast to conventional banks with recourse to collateral asset exercised only as a last option after incurring material administrative and legal costs. Seen from a risk-amelioration perspective, IF based on the cost-plus-profit model holds a promising future in the Indian financial sector as conventional banks become even more wary in expanding their balance sheet lest recognising higher provisions dent the profitability.

Contrary to the widely held perception, IF does not have to command an exclusive religious connotation. Ethical finance and sustainable finance are common acronyms for IF as the foundational bases remain similar. As the world is hosting COP28 in the UAE, even Climate Finance holds semblance with IF. The ongoing deliberations at the historic COP28 in Dubai, UAE is witnessing some of the biggest names in IF including the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB), based in Saudi Arabia, pledging financial support towards climate risk mitigation. By designing contracts in alignment with the socioeconomic status of debtors, IF is ideally well-placed to bridge the financing gap. The concept of generating income through responsible investment rather than outright lending (as in conventional banks) remains the core edifice common to the trio of Islamic-Sustainable-Climate finance (ISC). Interest-free and prohibition of excessive risk remain chieftain features of IF with the former resembling an equity-finance and the latter abhorring refuge in derivate-like instruments deemed too risky to add value to an economy. Research in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 suggests banks and financial institutions embracing IF were relatively well-insulated from contagion partly owing to the fact most of these institutions did not hold mortgage-backed securities acting as a major drag on the balance sheets of conventional (interest-bearing) and investment banks.

Contrary to the widely held perception, IF does not have to command an exclusive religious connotation. Ethical finance and sustainable finance are common acronyms for IF as the foundational bases remain similar.

To understand IF better, it is useful to look at its structure from a balance sheet. In principle, IF institutions typically hold assets as opposed to advances ideally resembling a lease-like structure with the lessor (IF banks) leasing out assets in return for a series of lease payments with an option for the lessee to buy back at the end of the tenure. The bulk of the liabilities comprises equity-like instruments, deposits (with unique characteristics), and convertibles popularly known as ‘sukuk’ or Islamic bonds. A major edifice of IF rests on tracing every commercial transaction to an asset capable of generating income obviating the need to engage in speculative trades. Embedded in the structure is spreading the risk between the institution and consumer as risks in a traditional debt tilt heavily towards borrowers. With efficient and effective recourse to assets, it is conceivable to observe lower levels of NPA and higher profitability attributed to IF institutions.

India holds tremendous potential to embrace IF to meet its developmental finance needs. IF envisages objectives synchronous with inclusive finance. With microfinance dominating the landscape in urban areas, IF holds significant potential to serve the country’s economically weaker section ideally well dispensed to benefit from the expansion of the formal financial system. India remains one of the most active start-up hubs of the world with an equally burgeoning need for efficient capital ideally dispensed to tackle emerging risks peculiar to the start-up business. With equity participation as the ‘force majeure’, the thriving entrepreneurial ecosystem can significantly benefit from IF without imposing draconian return mandates typical to venture capital imposing potential constraints. Following the successful presidency of G20, India can learn greatly from its predecessor—Indonesia—which is also on track to grow its economy exponentially on the back of a growing financial landscape with a strategic role accorded by IF in fuelling capital and consumption needs. Indonesia’s embrace of IF through micro-finance—built on an equity model—provides a sound example of empowering its economically vulnerable population by providing access to finance and generating sustainable income through voluntary training by developing employability skills. India’s microfinance sectors have traditionally focused on ‘urban poor’ and concentrated in relatively prosperous West and Southern India opening opportunities for IF-based MFIs to explore untapped potential, particularly in the Eastern belt. As India seeks to achieve financial inclusion, it is inevitable to reach a larger chunk of the population by developing robust self-sufficient social enterprises with capital coming through IF-MFIs. Malaysia too has successfully employed IF to achieve its economic goals counted among the most important destinations within its financial ecosystem. Home to the Islamic Capital Markets (ICM), the country boasts of an exclusive central bank structure to monitor, supervise, and spearhead the development of IF institutions to serve the financing needs of different sectors of the economy.

India holds tremendous potential to embrace IF to meet its developmental finance needs. IF envisages objectives synchronous with inclusive finance.

India, too, has an opportunity to facilitate FDI by enlarging the scope of foreign banks by allowing specialist IF institutions to set up branches under the direct remit of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). In its existing framework, RBI would have to expand its framework to permit the functioning of IF-Banks, which will initially mimic the structure of SFBs even as the underlying remit of the financial contract (viz. interest-free) remains unchanged. SEBI as a capital market regulator too could expand the framework to allow FIIs from IFIs to invest in India by ideally domiciling operations locally to support long-term investment and growth. The scope of IF in this space remains enormous including private equity, mutual funds and financial services. The scope of joint ventures with leading public and private sector banks could also open vistas of opportunities to serve the financial needs of different sectors of the economy. Consumer lending, commercial finance and infrastructure are some of the pivotal areas that could benefit from such partnerships as each of these sectors directly contributes to the GDP. Moreover, given the excessive risk-aversion on the back of NPA, for India to realize its potential the size and scale cannot warrant scarcity of capital to rule the roost. With its emphasis on interest-free lending, surely, India’s corporate sector would more than welcome an entirely new avenue of capital founded on the basis of risk amelioration. A regulatory sandbox could provide an incentive to evaluate the robustness of the system as well as to adapt IF to meet the specific needs of the Indian financial sector.

India’s deep-rooted historical, cultural, and business ties with the Middle East and GCC nations, in particular, hold enormous potential to attract foreign investment through specialist IF institutions operating in these countries who already have the experience of serving India’s rich diaspora prominently dispersed across the region. It would also pave as an alternative channel to attract NRI investments from the strategically significant geoeconomic region. At a time when India is looking ahead with optimism to break into the top three economies in the world soon, IF could serve as a strategic stimulus to meet the burgeoning needs of the economy.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Ullas Rao is a leading academic and financial economist based in Dubai, UAE with stints in prestigious institutions in India and UAE.