Erdogan’s boisterous efforts to revivify Islamist Turkey, viewed in conjunction with his equally headstrong approach to foreign policy has been dubbed ‘neo-Ottomanism’ due to its resemblance to the conduct of the former empire that reigned in Turkey for over five centuries.

A month after he converted the fabled Hagia Sophia, a cathedral-turned-mosque-turned-museum, into a mosque again, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has opened the Chora Church in Istanbul for Muslim worship. This is the latest in a series of moves by Erdogan to remake his country’s image from a staunchly secular, pro-western nation-state into a devout Islamic state.

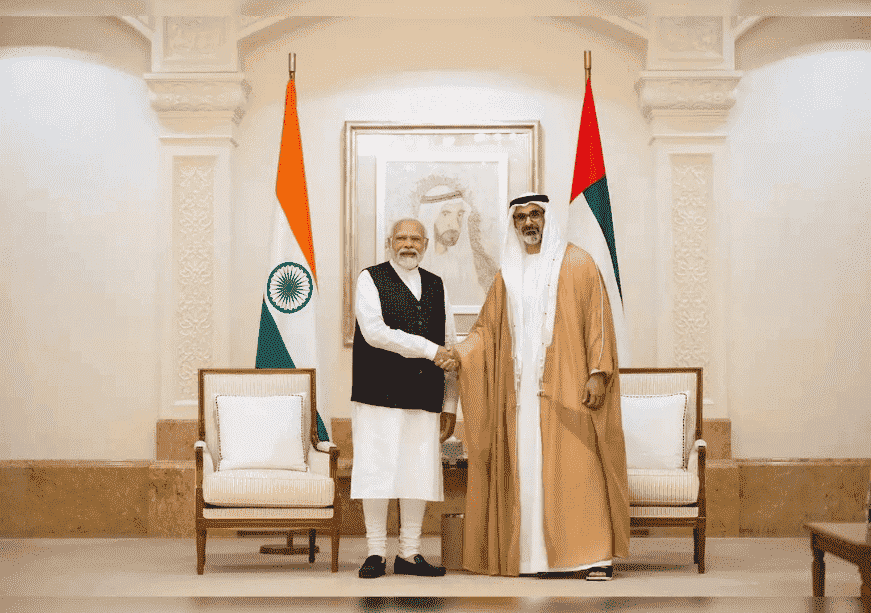

Such an attitude is evident in his hostility toward Israel for its occupation of the West Bank and in other occasions when he came out in solid support of pan-Islamic causes. As he delivered his speech on Hagia Sophia’s conversion, he said that next in line was the ‘liberation’ of Al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem, the third holiest site in Islam. Erdogan’s angry reaction to the ‘peace deal’ between Israel and the UAE was striking especially when compared to the loud silence of the Arab countries on the issue. Erdogan’s boisterous efforts to revivify Islamist Turkey, viewed in conjunction with his equally headstrong approach to foreign policy has been dubbed ‘neo-Ottomanism’ due to its resemblance to the conduct of the former empire that reigned in Turkey for over five centuries.

Domestic political imperatives

Presiding over the right-wing Justice and Development Party (AKP), Erdogan has been in power now for over 16 years. Being well-ensconced in his position, however, has not made him immune to political threats from the opposition. He suppressed an attempted coup d’etat by his own military in 2016 that sought to overthrow him. In 2018, he introduced the executive presidential system, considerably reducing the authority of the judiciary and the parliament. Fatigue of the Turkish masses with Erdogan’s rule was manifest in the Istanbul mayoral elections in 2019 in which Ekrem İmamoğlu of the Republican People’s Party (CHP) trounced AKP’s candidate not once but twice, after Erdogan called a rerun. That AKP took a drubbing in Istanbul, the cradle of Erdogan’s political rise, points to the precariousness of his current position.

“Erdogan’s recourse to historic symbols such as Hagia Sophia and the Chora Church are attempts to salvage himself from the political morass he finds himself in.”

For good measure, local governments have received plaudits for their adept handling of the Covid-19 pandemic which has led to comparisons with Erdogan’s own approach towards the pathogen. Erdogan’s recourse to historic symbols such as Hagia Sophia and the Chora Church are attempts to salvage himself from the political morass he finds himself in. Pandering to the population’s predilection for glorifying totems of the Ottoman empire might protect him in the short-term. But as vox populi steadily tilts against his favour, Erdogan has to find different ways to retain his position in the presidential elections scheduled to take place in 2023.

Regional supremacy

‘Neo-Ottomanism’ abroad roughly refers to a reinvigoration of Turkish influence in the Middle Eastern region and making Ankara the pre-eminent power in the neighbourhood. The driving force behind Erdogan’s assertive foreign policy is his ambition to achieve regional supremacy in the Middle East. Erdogan sent his troops to North Western Syria last year in order to expel the People’s Protection Units (YPG), a Kurdish militia that helped the US in its fight against eliminating ISIS. Turkey now enjoys de facto control over substantial swathes of territory in northern Syria where the Turkish lira is the recognised currency.

“The bad blood between Turkey and the Gulf states harks back to the Arab Spring of 2011. Ankara was actively supporting the protests, detesting the long-reigning Arab monarchies in favour of the blossoming of moderate Islamist groups and their entry into politics.”

The engagement in Syria has brought Turkey in the crosshairs of the oil-rich Gulf monarchies. Saudi Arabia and UAE have placed their bets on Syrian President Basher-al Assad who seemed to be on the brink of an overthrow until when in 2015 Russia and Iran decisively intervened to prop him up. The bad blood between Turkey and the Gulf states harks back to the Arab Spring of 2011. Ankara was actively supporting the protests, detesting the long-reigning Arab monarchies in favour of the blossoming of moderate Islamist groups and their entry into politics. Erdogan portrayed Turkey as a model of political Islam which was compatible with democracy. When the despot Hosni Mubarak was overthrown in Egypt and Mohammed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood won power in a democratic election, Turkey was overjoyed. However, the rulers in Saudi Arabia and UAE, in deep dread of a spill over effect that might also eventually have them overthrown, led concerted efforts to depose Morsi and aided the rise of Abdel Fatteh al-Sisi, the current president of Egypt.

As Arab Spring failed to deliver what Turkey expected it would, its hostility toward the Gulf States deepened. Saudi Arabia harbours a unique malice against Ankara due to Erdogan’s endeavour to pose as the rightful representative of Sunni Muslims around the world. Simultaneously, Turkey’s solidarity with Qatar, the only Gulf state actively supporting political Islam, also expanded. Now, Doha remains Ankara’s only ally in the region.

“As refugees fleeing the civil war in Syria arrived on Turkey’s shores, Erdogan threatened to open the door for them into Europe. With that move, Ankara lost its standing as a reliable gatekeeper and also began to lose its moral case for entry into the EU.”

Another dimension of Erdogan’s quest for supremacy is his disdain for the West, not least towards America. Erdogan’s approach towards the West belie Turkey’s previous image of a pro-Western NATO ally seeking admission into the European Union (EU). This change was exemplified by Erdogan’s willingness to use the refugee crisis in 2015 as a political bargaining tool with Brussels. As refugees fleeing the civil war in Syria arrived on Turkey’s shores, Erdogan threatened to open the door for them into Europe. With that move, Ankara lost its standing as a reliable gatekeeper and also began to lose its moral case for entry into the EU. Just last year, he did the unthinkable by procuring the S-400 missile system from Moscow, plunging the Western security alliance into consternation. Imposing sanctions would definitely be a strong possibility if Erdogan makes another move that dismays Washington.

Disputes with Mediterranean neighbours

The eastern Mediterranean region has been a strategically significant area for Turkey. Erdogan’s military intervention in Libya is a case in point. He has deployed the Turkish army and mercenaries from Syria to prop up the UN-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA) in Tripoli. On the other hand, UAE, Saudi Arabia and Egypt provide arms and ammunition to the rival Libyan National Army (LNA) led by the renegade military chief Khalifa Haftar, flouting a UN-arms embargo. Turkey’s success in warding off the threat from the LNA prodded al-Sisi of Egypt to consider directly intervening in the conflict.

“Erdogan has also antagonised the EU by refusing to recognise the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of neighbouring Cyprus and Greece in their eastern Mediterranean shores.”

Erdogan’s engagement in Libya can be explained by his deeper economic aspirations in the country’s coast. Erdogan signed a deal with Fayez al-Serraj, the Prime Minister under the GNA, that granted Turkey rights to drill for oil and natural gas in Libyan shores. This agreement was denounced by the EU as infringing ‘upon the sovereign rights of third states does not comply with the law of the sea.’

Erdogan has also antagonised the EU by refusing to recognise the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of neighbouring Cyprus and Greece in their eastern Mediterranean shores. Erdogan unilaterally sent drilling equipment into Cyprus’ marine territory in 2018 and conducted operations which led to Turkey being denounced as a ‘pirate state’ by Cyprus. His reluctance to find a diplomatic solution to the dispute was evinced in his speech on August 26 in which he said ‘Turkey will make no concessions in the eastern Mediterranean.’

Realignment

Erdogan has indirectly contributed to closer relations between its hostile neighbours. An axis of anti-Turkish states determined to secure their right to the minerals in their nautical territory has crystallised lately. The EastMed Gas Forum was formed last year by Cyprus, Greece, Israel, Jordan, Italy and the Palestinian Authority to pose a united front towards a belligerent Turkey. France, a country vocally critical of Erdogan’s exploits in Libya and elsewhere, applied for membership in the organisation early this year. Faced with such redoubtable opposition, it remains to be seen how Erdogan would handle the pressure while also securing Turkey’s interests in the region.

“Tehran has borne the brunt of President Trump’s maximum pressure campaign and shares an animosity toward Saudi Arabia and UAE with Ankara.”

At the same time, there has been a detente between Iran and Turkey, despite their differences in Syria. Tehran has borne the brunt of President Trump’s maximum pressure campaign and shares an animosity toward Saudi Arabia and UAE with Ankara. Foreign Minister Javed Zarif of Iran said in a statement that his country supports the Turkey-backed GNA in the Libyan conflict. The two countries view the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Force in Syria as an enemy. Iran also maintains ties with Qatar, a close ally of Ankara’s.

Circumstances have engendered a sort of ‘alliance of pariahs’ between Turkey, Qatar and Iran in the Middle East. However, the strategic convergence between Iran and Turkey is not likely to last long. If America decides to ease economic pressure on Tehran and take a non-confrontational approach (which will be likely in a Biden presidency) or relations warm between Iran and the Gulf monarchies, the Islamic Republic’s new-found affinity with Ankara will cease to be of much significance.

Conclusion

Forceful imposition of Islam at home and bellicosity abroad have animated Erdogan’s presidency. Presiding over unwieldy military engagements has taken its toll on the treasury. The military is over-stretched and the economy is taking a slump. This combination has spawned conditions at home that contribute to Erdogan’s sagging popularity. His recourse to displaying Turkey’s Islamic heritage through symbols like Hagia Sophia is a desperate attempt to boost his popularity and might not guarantee his political survival in the long-term. Soon, he might realise he has bitten off more than he could chew.

The author is a research intern at ORF.