Since 2024, Bahrain has started revealing the skeleton of what will emerge as a national Vision 2050. While the launch and the details of the Vision remain largely unknown, it has largely intrigued citizens, especially as the Vision 2030 remains under implementation due to several challenges over the years. The strength of this Vision is that it encompasses various topics of interest aside from economic goals, such as societal development aims. A vision of this calibre can set the tone of how national identity in the Kingdom evolves by the middle of the century.

In October 2024, during the third Royal Address of the Sixth Legislative Term, the King of Bahrain, Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa, underscored “the importance of completing the plans derived from the Bahrain Economic Vision 2030,” while mentioning that “work is accelerated on its next version for the year 2050”. Months earlier, the Crown Prince and Prime Minister Salman bin Hamad al-Khalifa directed the cabinet to commence consultations on Vision 2050, “with the legislative authority, the private sector, professional institutions, and civil society organisations”.

The Quiet Formation of Vision 2050

More than a year later, it remains unclear what consultations have been held. In a recent July 2025 interview with some politicians, a local newspaper, Akhbar al-Khaleej reported statements attributed to two MPs, Maryam Saleh al-Dhain, and Abdullah Hasan al-Dhaen, that hinted such consultations may be taking place. It appears that these consultations are happening behind closed doors with select representatives. However, this has not prevented any leaks to the press. In July 2025, BFT Media, an active social media account focused on Bahrain’s economy, revealed key principles of the Vision. It claimed that Vision 2050 will focus on 1) investing in human capital; 2) improving infrastructure; and 3) supporting the legislative environment. The new vision, it is claimed, is driven by these three key words: human, infrastructure, and legislation.

Sheikh Nasser bin Hamad al-Khalifa, the King’s Representative for Humanitarian Work and Youth Affairs, recently delivered a keynote address at the 28th Saint Petersburg International Economic Forum 2025 (SPIEF). He noted that Vision 2050 will focus on “innovation, digital transformation, sustainability, and income diversification”. He also highlighted human capital and “investment in people as the foundation for national progress”.

Vision 2030: Achievements to Date

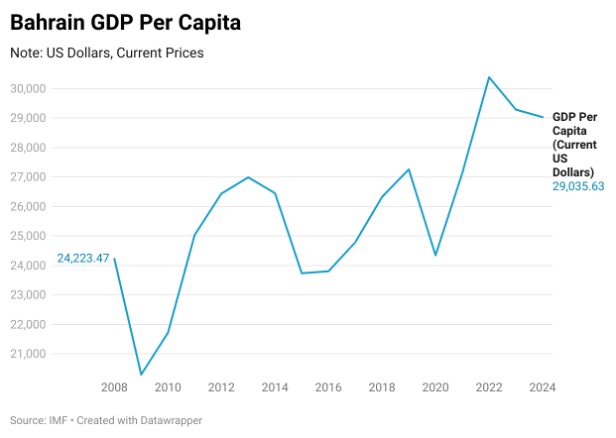

Looking ahead, such a vision must be measurable. The Vision 2030, launched in 2008, had several KPIs included in it. Below is a summary of the achievements in Bahrain since its launch. Firstly, Bahrain set out to enhance productivity and skills, said to be tracked through metrics such as real GDP per capita growth, amongst others. While GDP per capita is typically reported by credible sources in current prices (which may not reflect real GDP per capita), it indicates the magnitude and the trend of growth. It is also worth noting that while per capita measures are useful, it is still susceptible in the case of Bahrain to the ‘Will Rogers Phenomenon’ due to the large amounts of migration the country experiences—the Kingdom’s Human Development Report from 2018 has a box which explains the potential shortcomings of such a measure. Nonetheless, between 2008 and 2024, the change in GDP per capita was US$ 4,812.16, a change of 19.9 percent according to the International Monetary Fund.

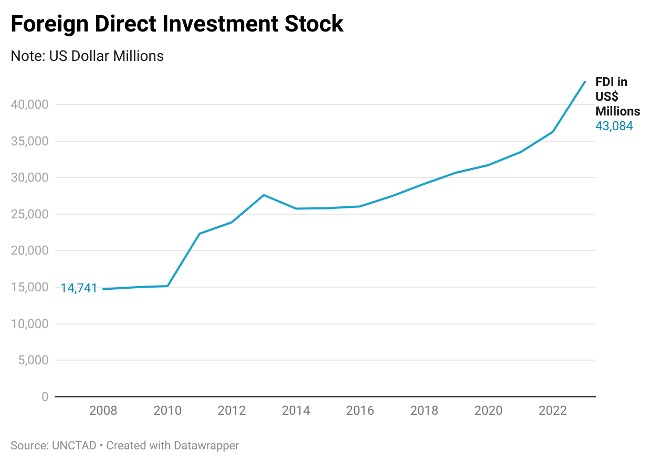

The second measure under this pillar was Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). On this measure, the change between 2008 and 2023 in terms of FDI stock was US$ 28,343 million, a change of 192 percent, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Notably, the Vision 2030 does not specify whether this should be measured in flows or stock.

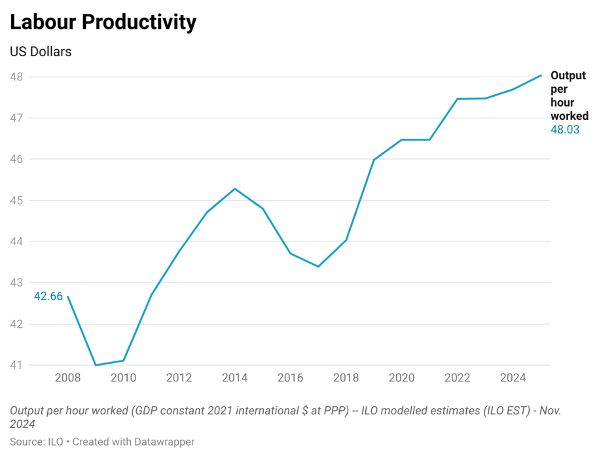

The third measure under this pillar is productivity. According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), Output per hour worked (GDP constant 2021 international $ at PPP) rose from 42.66 to 48.03 between 2008 and 2025.

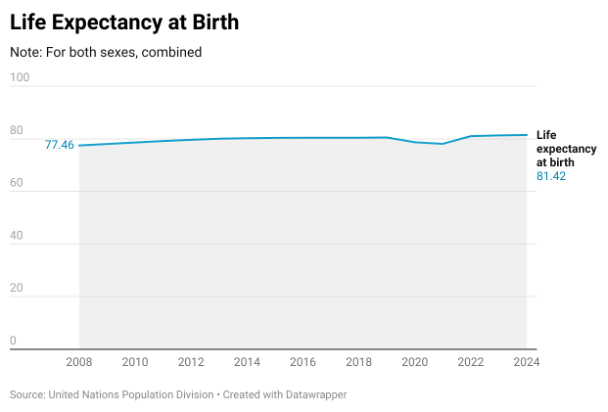

Other successes exist too in other pillars. Under the quality healthcare pillar, Bahrain aimed to raise life expectancy. According to the UN Population Division, this has improved by almost four years since 2008, reaching 81.42 years for both sexes in 2024.

Measurements in Flux

However, some metrics are hard to track. One such measure is the number of new medium-to-high wage jobs held by Bahrainis, and the government’s open data portal lacks such data reporting. The case is similar to the public sector wage bill as a share of GDP, or the share of households earning above the national minimum income, and even the share of recurrent expenditure financed by recurrent revenues. Some raw data can be calculated, but it remains unclear why the government has not provided those calculations. For example, data on the goal of improving educational institutions in independent quality reviews and examinations, or data on improvements in provider performance according to healthcare regulatory standards, can be researched, but given that they are mentioned in the Vision, perhaps they ought to be collated and summarised by the government. Where the government does collate it, such as the case with Bahraini labour participation, it is sporadic. The case is similar to the concentration of air and water pollutants, which is not fully captured by the Supreme Council for Environment’s open data.

In another example, Bahrain’s Vision 2030 sought to “transform the economy in the longer-term by capturing emerging opportunities”. This would focus on knowledge-based sectors and increasing the output of high-value-added goods and services. The parameter set out was quite vague, and the future vision could benefit from a detailed identification of such emerging sectors, as it did with “high-potential” sectors such as tourism, business services, manufacturing, and logistics.

Additionally, as part of an objective of focusing on “developing high quality policies”, creating “predictable, transparent and fairly enforced regulatory system”, and the public sector becoming “more productive” and “accountable for delivering better quality services via leaner organisations and operations”, Vision 2030 relied on World Bank data for these measurements. This included the ‘quality of administration index’, the ‘public-sector accountability index’, the ‘regulatory quality ranking’, and the ‘ranking for government effectiveness and accountability’.

The changing nature of how the World Bank captures these measures to date means it’s slightly unclear whether the latest world governance indicators by the World Bank are wholly useful to evaluate the vision. It appears some of the above indicators were discontinued. Nonetheless, the following are some of the available indicators. Bahrain’s percentile rank went down from 23.08 in 2008 to 11.27 in 2023 on the voice and accountability indicator. In the government effectiveness indicator, it went up from 66.5 in 2008 to 74.53 in 2023. Lastly, in the regulatory quality indicator, it went up from 72.33 in 2008 to 83.96 in 2023.

This may indicate that using international calculations as part of the KPIs is a mistake and that it requires backup measures. The World Economic Forum’s infrastructure ranking has not been updated for several years, and the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Livability Index is hard to access in full time series, harming the transparent tracing of the Vision’s achievements.

Conclusion

As Bahrain drafts its new vision, and likely inspires neighbours to do the same, an evaluation of 2030 was necessary. Moving forward, more transparency is needed on the process in place to draft the vision. Snippet details being revealed here and there about this vision may distract people from its ultimate goal: unity around national prosperity. It also takes away from the royal directives to make this drafting process a truly participatory one. Moreover, if the evaluation of the Vision 2030 reveals one thing, it’s that the KPIs of Vision 2050 ought to be clear, consistently measured, and shared.

Mahdi Ghuloom is a Junior Fellow, Geopolitics at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) – Middle East.