The fragile ceasefire announced in late June 2025 has paused the missile exchanges over the Middle East, but it has not silenced the alarms ringing through Iran’s economy. The direct military conflict with Israel and the United States (US) has tipped a nation already under immense strain into a state of acute economic crisis. The Iranian rial fell to a historic low, trading at 1 million Iranian rials to a US dollar. This collapse is not the result of a single factor, but the culmination of a vicious cycle rooted in structural dependency on oil, crippling international sanctions, and the unyielding financial demands of strategic programmes, which have adversely impacted national currency along with the lives of ordinary Iranians.

At its core, the Iranian economy suffers from a profound, decades-old dependence on oil. The energy sector, accounting for about 70 percent of total exports, has been the engine of the state, forms the bedrock of the government’s budget. This over-reliance has created a critical vulnerability, a single point of failure that international sanctions have expertly targeted for years. Decades of restrictions, massively intensified by the “maximum pressure” campaign, have systematically severed Iran’s access to the global economy. Sanctions have not only drastically slashed Iran’s official oil exports, from a peak of over 2.5 million barrels per day to 20 percent of that in 2024, but have also excommunicated its financial sector from global networks like SWIFT. This has made legitimate trade nearly impossible, starving the country of the foreign currency needed to import everything from industrial machinery to essential medicines.

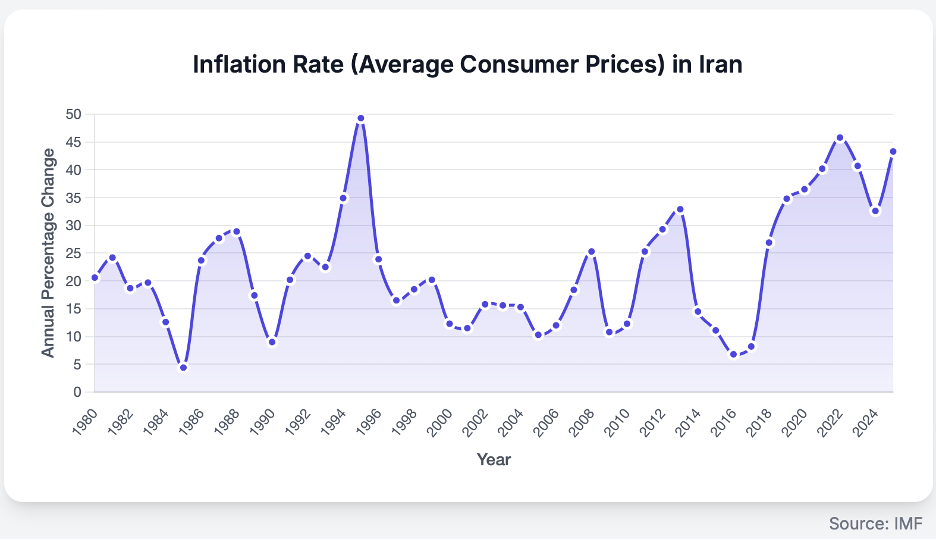

This chronic shortage of foreign currency reserves is a significant driver behind the catastrophic collapse of the Iranian rial. The government, deprived of its primary source of revenue and unable to borrow internationally, has been forced to cover its massive deficits by printing money. This has increased the inflation rate, which the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has estimated at over 43 percent, one of the highest in the world. The inflation rate is on an upward trajectory once again, after a brief reduction in 2024 (Graph 1). This has effectively wiped out the purchasing power and life savings of the Iranian population. The freefall of the rial is the most visible symptom of this deep-seated economic disease, where the cost of basic food items can surge frequently, making survival a daily struggle for millions.

This dire economic situation is compounded by the regime’s strategic priorities. Despite the economic sanctions, Tehran still manages to export oil to countries like China through elaborate mechanisms and networks like alternative currency payments and front companies. This also forms the bedrock for a state-sanctioned ‘resistance economy’, which operates in the shadows and fuels a vast black market for currency and goods. These resources are used to fund Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile programmes, creating an impossible trade-off. Revenues earned from oil sales cannot be used to defend the rial’s value or subsidise essential imports. This creates a feedback loop: as external pressure mounts, the regime perceives its strategic programmes as more essential for survival, thereby diverting even more scarce resources away from the collapsing economy, which in turn fuels further social and economic instability. The result is an economy trapped between harsh international sanctions and its own aggressive goals.

The Path to Economic Recovery

Iran’s economic crisis is not just a macroeconomic dilemma; it is a daily hardship for millions. From the collapse of the rial to sharp inflation, the geopolitical costs are being paid by ordinary Iranians. As a result, economic recovery is increasingly becoming a national imperative. Tehran can begin charting a course out of economic freefall by recalibrating its international and national economic strategies. Internationally, revival of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and Financial Action Task Force (FATF) compliance could unlock vast reserves of capital and credibility. On the domestic path, currency reform and smart de-escalation could stabilise the economy and rebuild public confidence. Together, these strategies can provide the much-needed stimulus to the Iranian economy.

On the international front, the JCPOA is not merely a diplomatic agreement; it represents the most viable path to economic recovery. Its potential revival offers a powerful “dual dividend”: the immediate relief from crippling economic sanctions and the strategic opportunity to redirect billions from a costly nuclear program toward national recovery. Comprehensive sanctions relief goes far beyond simply being able to sell oil legally. A revived deal would reconnect Iran to the global financial system, drastically lower transaction costs for trade, unlock over US$100 billion in frozen assets abroad and signal to the world that Iran is open for the foreign investment needed to modernise its economy. The second, often overlooked, benefit is the “peace dividend.” The immense national resources, financial, technical, and human, currently dedicated to maintaining and advancing a high-level nuclear programme, could be strategically reallocated. The capital spent on advanced centrifuges and fortified underground facilities could instead fund social safety nets and rebuild infrastructure, thereby alleviating the economic hardships of Iranians. This dual effect is why the JCPOA remains the most potent solution to Iran’s economic crisis.

Despite the compelling economic logic, the deal is paralysed. The reasons are rooted in a profound lack of trust and deadlocked domestic politics. In Washington, there are persistent demands to expand the deal to cover Iran’s ballistic missile program and its regional activities, though the “Axis of Resistance”, issues Tehran considers non-negotiable pillars of its national security. From Tehran’s perspective, the US unilateral withdrawal in 2018 is the foundational breach of trust. Hardline factions argue that the US cannot be trusted and demand guarantees against a future withdrawal, a guarantee that would be constitutionally and politically hard for the US President to provide. Furthermore, powerful entities like the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) have established the sanctions-busting ‘resistance economy’. For some within this faction, a full economic opening to the West is not an opportunity but a threat to their current political and economic dominance over the black-market economy. Tehran should aim at circumventing these issues by calculated political shifts, specifically by co-opting the IRGC. A sustainable recovery is impossible if the state’s most powerful institution remains invested in a parallel economy.

Another complementary priority must be to tackle a significant obstacle to Iran’s economic reintegration: its blacklisting by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). Compliance with FATF standards on anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism is the essential key to unlocking the global banking system. Without it, sanctions relief remains a hollow victory. Recent progress highlights the deep divisions on this issue within the Iranian establishment. In a significant development, Iran’s Expediency Council approved the Palermo Convention against transnational organised crime, a key FATF requirement. This move, championed by President Masoud Pezeshkian’s government, signals a clear push toward international compliance to attract investment and ease trade. However, the final, most contentious hurdle, the Combating the Financing of Terrorism (CFT) bill, remains. Hardline factions, particularly those aligned with the IRGC, argue that full compliance could hamper their support for regional allies like Hezbollah, viewing it as a threat to a core pillar of their ideology and power. This sets the stage for the ultimate political gambit for Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: shepherding the IRGC’s transition from a spoiler to a stakeholder, positioning its vast engineering and logistical arms as primary partners for foreign investment. Only by resolving this internal conflict and achieving FATF compliance can Iran ensure that the path to economic recovery is politically feasible.

While the diplomatic and political stalemate is resolved, Iran should try to provide the much-needed economic stability to its population through domestic reforms. An effort in this direction, that should be approached with caution, is the redenomination of its national currency. Central Bank Governor Mohammad Reza Farzin announced earlier in 2025 that the plan to strike four zeros from the rial and formally replace it with the “toman” would be implemented this year. The new system would peg one toman to 10,000 rials. While this would not end the economic hardship, it could be a psychological move that provides an immediate break from the optics of inflation. A study by Karnadi and Adijaya concluded that redenomination can decrease the inflation rate and increase the level and growth of real GDP per capita. However, this study also suggests that redenomination policy will not be effective if a country is politically unstable. Therefore, political stability must be achieved in Iran for redenomination to have the desired impact. Concurrently, Iran can work to create a more favourable environment for eventual negotiations through quiet de-escalation. By taking modest, reversible nuclear steps, such as halting enrichment at higher purities, it can build goodwill and reduce international pressure. This could encourage a tacit relaxation of sanctions enforcement on oil sales, providing a vital economic lifeline without the political cost of a rapid escalation.

In conclusion, Iran’s recovery will not come from grand bargains alone. It will hinge on quiet recalibrations. The real test is not just what Tehran concedes abroad, but also what it reclaims at home. To escape economic freefall, the regime must refocus from resistance to recovery.

Samriddhi Vij is an Associate Fellow, Geopolitics at the Observer Research Foundation–Middle East.