Against the backdrop of adversity and tensions which redefine trade cooperations and economic exchanges, the European Union (EU) has recognised its vulnerabilities and dependencies and has adopted an increasingly assertive approach to commercial policies, in line with its ‘Open Strategic Autonomy’ concept. Consequently, the Union seeks to elevate its economic cooperation to a higher level with countries in its wider neighbourhood, strategic partners with whom it has shared interests and overlapping priorities on open trade. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) meets all these criteria.

For the UAE, the EU is its “second-largest global trade partner”, with increasing shares of non-oil trade, whereas for the EU, the UAE is a main market for its goods and services in the Gulf and its “biggest foreign direct investment partner in the region”. Based on their mutually beneficial commercial cooperation, and considering that “in this fragmented world strategic partnerships are the most important currency”, the parties announced in April 2025 the launch of a Free Trade Agreement negotiation (FTA)[1].

Impact on the GCC-EU FTA Talks

A bilateral FTA with an individual Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) country, and not with the GCC itself as a regional block, “is a departure from the EU’s historical position”. Region-to-region negotiations were launched almost two decades ago but got suspended in 2008 due to a lack of a mutually acceptable deal. However, this does not indicate a loss of interest on either side. The first-ever EU-GCC Summit was held in October 2024, to be repeated in 2026 in Saudi Arabia. Moreover, during the summit, both parties committed to restarting FTA talks.

However, the EU has openly stated that the bilateral agreement with the UAE “can serve as a catalyst for stronger ties between the EU and the Gulf Cooperation Council”. Luigi Di Maio, EU Special Representative for the Gulf, has equally pointed out that the EU-UAE FTA represents “a building block toward a regional Free Trade Agreement”. As such, the Union does not see the EU-UAE and EU-GCC FTAs as exclusive. The successful conclusion of an agreement with the UAE, if it delivers, could provide a new impetus for region-to-region negotiations. The same perspective has been shared by The UAE’s Minister of Foreign Trade, Thani al-Zeyoudi, who has publicly stated that the bilateral talks between the EU and the UAE are not a hurdle to a region-to-region FTA, but rather “a flow which is going to be starting from here and moving to the GCC”.

Precedents exist. New Zealand concluded a bilateral trade deal with the UAE just months before finalising a GCC-wide agreement. Similarly, Pakistan entered bilateral talks with the UAE after signing a preliminary FTA with the GCC. South Korea signed an FTA with the GCC shortly before reaching a bilateral deal with the UAE. Türkiye took the reverse path, launching GCC negotiations nearly a year after its bilateral agreement with the UAE. Other countries, such as Australia, Malaysia, and Chile, have signed bilateral deals with the UAE while still in earlier stages of pursuing GCC-wide agreements.

An alternative scenario一a transition path一which could potentially set the stage for a region-to-region FTA, might materialise in multiple bilateral Free Trade Agreements concluded between the EU and individual GCC countries, alongside the UAE. The logic of such an approach seems to gain traction within the EU, as the Council recently adopted the mandate to “enter into negotiations with each of the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries” to conclude bilateral Strategic Partnership Agreements (SPAs) with all of them. Trade and investment would be one of the main components of these partnerships. However, complementary to the SPAs, the potential of bilateral FTAs with all GCC countries is highly dependent on their projected economic benefits and viability for the parties involved.

Remaining Obstacles

While the UAE has stated it expects the negotiations to take a few months, and the EU has shown a gesture of goodwill by removing the UAE from its money laundering watchlist, obstacles remain between the two parties. The first round of negotiations between the EU and the UAE was held between 24 June and 9 July this year. The EU had tabled proposals for the FTA chapters ahead of the round, with the second round of negotiations scheduled to take place in Brussels in September 2025.

Capitalising on its market power, the EU has been using trade negotiations to “externalise its social” and development agendas, thereby shaping third parties’ policies in these fields. The EU’s stance on human and labour rights, in addition to the oil industry, has been a key obstacle behind the stalling of the GCC-EU FTA negotiations, for example. It remains a key issue with a new impact assessment focused on such topics being tendered by the EU about the GCC-EU FTA negotiations. The same obstacle appears to reappear in the tabled text proposal by the EU to the UAE, continuing to focus on human rights, labour, and sustainability commitments.

Potential Benefits: the ASEAN-EU analogy

The most apparent risk from an exclusive EU-UAE FTA is that it could trigger significant trade and investment diversion away from other GCC members. Saudi Arabia is historically the GCC’s dominant exporter to the EU. It consistently accounted for over 60 percent of the bloc’s total exports., These exports are heavily concentrated in the same sectors as the UAE’s. According to 2024 data, for Saudi Arabia, HS Code 27 (Mineral Fuels, etc.) accounts for 85 percent of its exports to the EU. Similarly, while the UAE has made strides in diversification, HS Code 27 still represents a substantial 49 percent of its exports to the EU.

This homogeneity in their primary export good – mineral fuels – means that any preferential access granted to the UAE for these products would directly impact Saudi Arabia’s competitive position in the EU market. If the FTA significantly reduces tariffs and non-tariff barriers for UAE oil and gas products, the EU is likely to increase its sourcing from the UAE. This would divert trade from Saudi Arabia, which lacks such preferential access.

However, a more optimistic scenario exists if the agreement is structured with regional integration in mind. On this, an analogy might be observed and analysed about one region that has faced a similar path as the GCC with respect to trade with the EU: the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Bi-regional trade negotiations were launched in 2007 and paused by mutual agreement in 2009 to give way to a bilateral format of negotiations, which were signed between the EU and Singapore (2014) and Vietnam (2015).

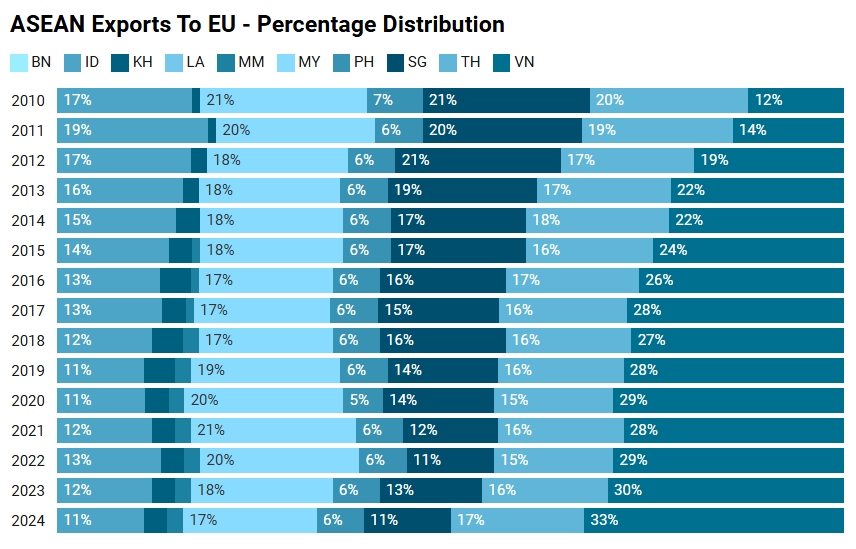

Assessing the trade post-FTA with the EU presents an interesting story for Singapore, with the figure below showing that after its FTA was implemented in 2019, Singapore’s share of the total ASEAN export pie declined, falling from 14% to 11% by 2024. A surface-level reading would suggest Singapore simply failed to benefit from its agreement.

However, a deeper insight helps solve the puzzle: the “ASEAN Cumulation” clause presents a compelling potential explanation. This clause is a specific provision within the EU-Singapore FTA that allows Singaporean companies to count materials and components sourced from other ASEAN nations as if they were their own. The “ASEAN Cumulation” clause has two primary mechanisms that allow for regional inputs. Some products can be included if they originate from an ASEAN country that has a separate Preferential Agreement with the EU. For other specified products, materials can be sourced from any ASEAN nation, even those without a direct FTA with the European Union. This provision has the potential to redefine what it means to be “Made in Singapore” for trade with the EU. This could explain a fascinating pattern in the data: the sustained and even accelerated growth in exports from Malaysia (MY), Indonesia (ID), and Thailand (TH) directly after the 2019 implementation of the Singapore FTA. It is possible that the cumulation clause created incentives for Singaporean firms to shift final assembly to these neighbouring countries to lower costs, while retaining control over the most profitable parts of the value chain. In this scenario, the export statistic is recorded in Malaysia or Indonesia, but the economic profit flows back to Singapore. The decline in Singapore’s goods export share might not be a sign of failure but rather could be a sign of a sophisticated strategy: it is benefiting not by shipping more boxes, but by acting as the indispensable economic brain for a thriving regional supply chain.

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the EuroStat Database

A “GCC Cumulation” clause, similar to the ASEAN model, could be similarly powerful in this regard. It would allow materials from neighbouring Gulf countries to be processed in the UAE and exported to the EU under the FTA’s preferential terms. This would create a powerful incentive for deeper intra-GCC supply chains. For example, Saudi Arabian raw petrochemicals could be processed into specialised plastics in the UAE’s advanced industrial zones, with both countries sharing the economic benefits of tariff-free export to the EU.

Notably, such a clause is missing in the EU’s tabled Rules of Origin proposal to the UAE. The only cumulation clause appears in Article X.3 (Cumulation of origin), which only allows bilateral cumulation between the EU and UAE, yet not regional cumulation with third countries. Both parties may seek to consider adding this clause to ensure the GCC-wide benefits are reaped.

Conclusion

The failure of the EU-GCC FTA talks and current political differences underscore the challenges of a region-to-region approach. While such talks continue, the EU appears open to exploring bilateral agreements with individual Gulf countries. However, as shown by ASEAN’s and Singapore’s trajectory, bilateral agreements, such as the one being negotiated between the EU and the UAE, if designed strategically, can evolve into broader regional gains.

Eszter Karacsony is an Associate Fellow and Program Lead in Geopolitics at Observer Research Foundation (ORF) Middle East.

Ahmed Dawoud is an Economist and the Head of the Data Analytics Unit at the Egyptian Center for Economic Studies (ECES).

Ahmed Wael Ahmed Habashy is an AI Engineer at the Egyptian Center for Economic Studies (ECES), specialising in the development of intelligent systems for labour market and economic analysis.

Mahdi Ghuloom is a Junior Fellow, Geopolitics at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) – Middle East.

[1] The European Union uses the terminology “Free Trade Agreement” whereas the United Arab Emirates refers to the same as “Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements” – diplomatic source.