Since November 2023, Houthi militants have conducted a sustained campaign against international shipping in the Red Sea, resulting in attacks on over 100 merchant vessels. This includes the sinking of four ships, the seizure of another, and the deaths of at least eight seafarers. The persistent attacks on commercial shipping in the Red Sea by Houthi militants have unleashed a cascade of complex and interconnected costs on the global economy. While the conflict is regional, its financial repercussions are global, extending far beyond the immediate operations. Nearly, 15 percent of global seaborne trade passes through the Red Sea, including 8 percent of global grain trade, 12 percent of seaborne-traded oil, and 8 percent of the world’s liquefied natural gas trade. As this trade is disrupted, there are multi-layered costs incurred because of this disruption including the direct expenses of military action and rerouting and the indirect costs to global supply chains. It is important to evaluate how these pressures are creating a new, more expensive paradigm for international trade.

Cost and Operational Implications

The most immediate economic damage stems from the attacks themselves, which weaponise not just munitions but risk perception. The sinking of vessels like the Rubymar represent a multi-layered financial shock: the loss of the carrier itself, the total loss of its cargo, and the subsequent cost of environmental cleanup from its hazardous fertiliser payload, creating a new category of liability for shipowners. The Sounion ship that was attacked in 2024 was carrying 922,000 barrels of Iraqi crude oil. Further, through these attacks the Houthis are reportedly blocking an estimated US$10 billion in cargo each day. When the UN launched a global appeal to remove a similar amount from a decaying floating oil storage and offloading vessel off Yemen, the clean-up costs of US$20 billion was estimated. More fundamentally, these events have impacted the psychological threshold of risk for insurers and shipowners, moving the threat from a manageable disruption to a potentially catastrophic destruction. Following the attack on commercial containers in early July 2025, risk premiums have risen to around 1 percent of the value of a ship, from around 0.3 percent the week before these attacks took place.

This is compounded by the immense cost of international naval patrols. Operations like Prosperity Guardian and the EU’s Aspides are not just defensive missions, but expensive ones. Each munition used to shoot down the Houthi missiles and drones costs between US$1 million and US$4.3 million. However, this socialises the cost of protecting global commerce, transferring the financial burden from corporations to the public treasuries of a few nations.

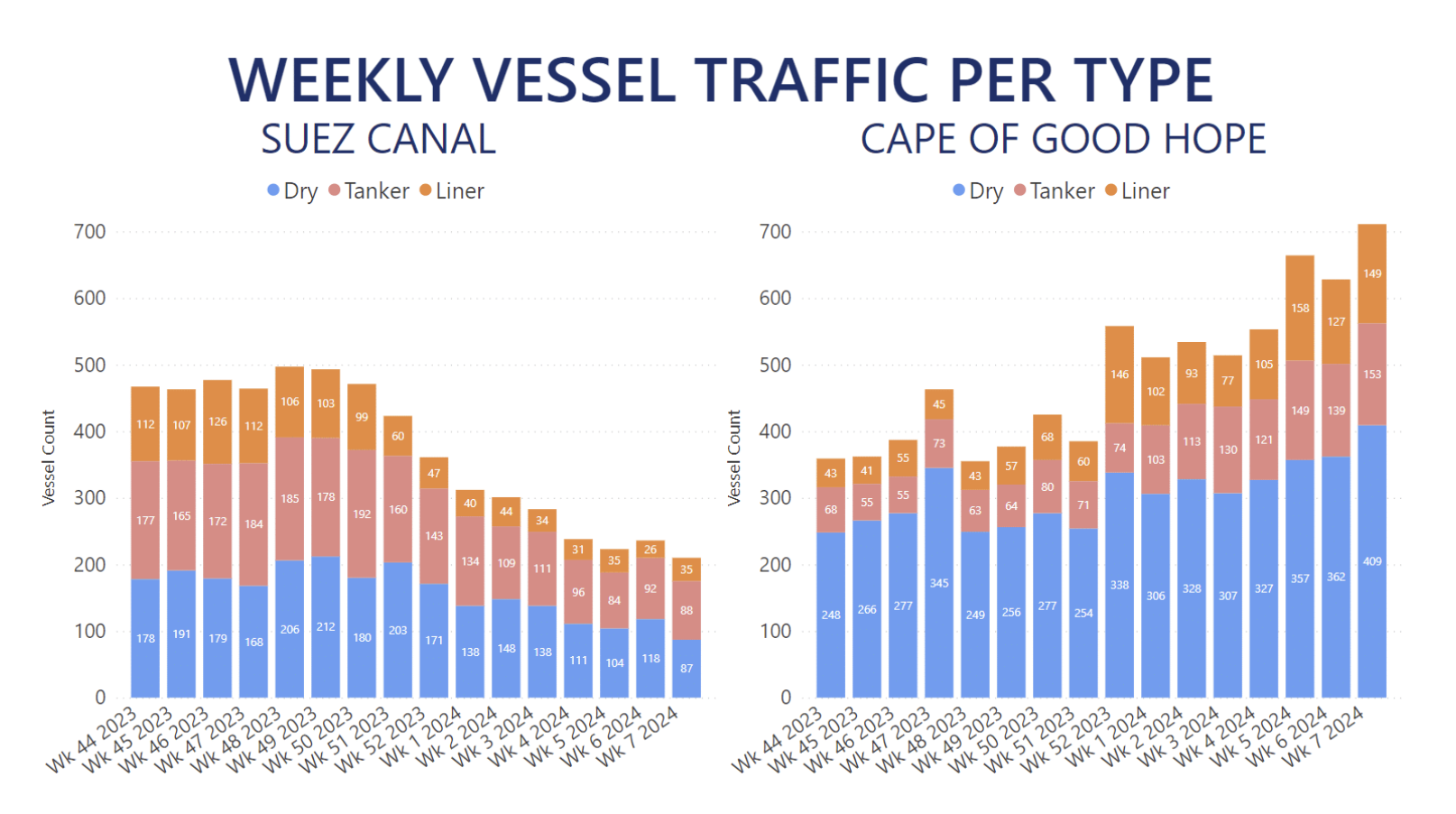

Shipping lines have rerouted around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope to avoid the Suez Canal as evidenced by Figure 1. This has triggered a cascade of compounding costs that extend far beyond fuel. In fact, the volume of trade passing through the Suez Canal dropped by about 50 percent in the first two months of 2024 compared with a year earlier. While the additional US$1 million in fuel per round trip between Asia and Northern Europe is significant in itself, the operational costs are much deeper. The longer 10-12 day journey increases wear and tear on engines, raises crew overtime costs and significantly boosts carbon emissions. This extended journey time has created a capacity crunch. With ships tied up for longer, the effective capacity of the global container fleet has shrunk by an estimated 9 percent, according to UNCTAD. This artificial scarcity allows shipping lines to impose dramatic rate hikes. For instance, Drewry’s World Container Index showed how the pricing for a 40ft container almost tripled in the initial months of the crisis.

Along with the direct shipping costs, the crisis has also impacted the “just-in-time” (JIT) manufacturing model, imposing significant indirect costs on businesses and consumers. The JIT model, which relies on predictable, low-cost shipping to deliver components exactly when needed, is unworkable in the current environment. Companies are now aggressively shifting to a ”just-in-case” (JIC) strategy, holding a significant amount of extra inventory as a buffer against delays. This creates massive hidden costs, tying up corporate capital in warehouses rather than in innovation or growth.

FIGURE 1

Source: AXSData

The Red Sea delays have also led to the “bullwhip effect”, where a small disruption at the source amplifies volatility and cost down the supply chain. This was seen when companies like Tesla and Volvo temporarily halted production at their European plants due to a shortage of components, incurring significant costs from lost production. This impact is also pronounced for the retail and apparel industry; the crisis has wrecked seasonal inventory planning, with shipments of time-sensitive fashion arriving too late, as the British retail chain Marks & Spencer warned that the turmoil would delay new spring clothing.

These costs are often passed on to consumers and can contribute to increased global inflation. As a result, a rethinking of the strategic implications of the Houthi attacks on the global economy and pathways for navigating its economic effects is important.

Navigation Strategic Implications on the Global Economy

The Red Sea crisis is not just a momentary disruption, it signals the structural reconfiguration of global trade under the shadow of persistent geopolitical risk. There has been an emergence of a new trade regime, where threat perception, not distance, cost or speed, becomes the primary variable shaping commercial decisions. For policymakers, this necessitates a fundamental rethink of how global trade routes are secured, financed and structured.

The immediate naval response, through operations like Prosperity Guardian and the EU’s Aspides mission, has been critical in restoring a degree of order. Yet, these military deployments come at an unsustainable fiscal and political cost. They externalise risk mitigation onto a handful of nations, while the benefits of stable maritime flows are distributed globally. This asymmetry calls for a multilateral burden-sharing mechanism, not just in military terms, but in the financial architecture. A pooled maritime risk fund under international frameworks like the International Maritime Organization, in which major trading economies contribute based on their dependence on global seaborne trade, could support both enhanced security deployments and subsidized insurance guarantees for high-risk corridors like the Red Sea.

Insurance reform is a parallel imperative. War-risk premiums skyrocketed in mere days, not because of actual losses but because of rapidly shifting risk psychology. This volatility trickles down into freight rates, inflation and consumer prices across continents. Governments and multilateral development banks should consider offering reinsurance backstops for critical corridors, much like terrorism reinsurance pools established after 9/11. These interventions would not distort markets, but rather smoothen extreme spikes, preventing short-term risk from becoming long-term inflation.

Beyond risk financing, the crisis has exposed deep vulnerabilities in global supply chain design. The just-in-time model, long hailed for its lean efficiency, has now become a liability in volatile shipping environments. National governments should incentivise resilience investments, such as nearshoring, dual sourcing or inventory buffers, through targeted tax relief and grants. In a world of cascading shocks, resilience is a strategic asset.

However, resilience must go beyond inventory; it must be spatially reimagined. With the Cape of Good Hope now a reluctant substitute for the Suez Canal, trade flows are longer, costlier and carbon-intensive. There is an urgent need to operationalise alternative corridors, both maritime and land-based. Investments in the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor, as well as enhanced logistics hubs in the eastern Mediterranean, must be fast-tracked and embedded with fast-lane customs protocols. Egypt has a strategic opportunity to reposition itself not only as a Suez Canal gatekeeper but as a regional transhipment node that can flexibly absorb shock-diverted cargo.

In tandem, trade architecture must become digital and predictive. The erosion of supply chain predictability, where retailers no longer know when their goods will arrive, is as damaging as physical losses. A coordinated platform for maritime risk tracking, cargo rerouting and digital documentation (leveraging satellite data and AI routing models) could bring real-time verifiability into trade flows.

All of this demands not just policy agility, but a new institutional mindset. The Red Sea crisis has exposed the absence of strategic foresight in trade governance. The threats to commerce are no longer just macroeconomic, they are asymmetric, decentralized and politically fragmented. Governments must establish foresight units that bring together defense, commerce and logistics to prevent the economic costs of chokepoint disruptions before they occur and design cross-sectoral responses.

Ultimately, the Houthis have not just disrupted cargo, they have exposed the fragility of global trade. The path forward lies not in restoring a previous equilibrium, but in building a risk-smart trade system. One that blends security with economics and geopolitics with supply chain design. Only then can global commerce thrive on foundations stronger than hope.

Samriddhi Vij is an Associate Fellow, Geopolitics at the Observer Research Foundation–Middle East.