Stretching over 6,400 km, from the Indo-Pacific to the Mediterranean, the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) is an ambitious intercontinental connectivity project. Its eight signatories include the European Union (EU), Germany, France, Italy, India, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and the United States (US)—from three continents. In addition, without being an official signatory, Jordan, Israel, Greece, and Oman[1] are also affiliated with the project due to their geographic location along the route. Other countries are equally interested in getting involved, like Egypt and Cyprus.

While IMEC’s geographic footprint provides an overview of the Corridor’s spatial layout, it does not capture its full scope and impact potential. IMEC is not merely an infrastructure project but a geostrategic concept[2]. This unique strategic character stems from the global geopolitical and economic context of the project’s inception in September 2023, announced on the sidelines of the G20 Summit in New Delhi, India. This era is marked by inter-state tensions and subsequent geoeconomic competition, leading to the increased instrumentalisation of trade schemes and supply chain dependencies. Recognising this challenge as well as the project’s growth prospects, IMEC has become both a geostrategic concept and tool. As such, it materialises through the establishment of structural interconnections between trusted economic partners in order to secure and diversify global value chains and remain competitive. Its competitiveness also lies in the development of infrastructures that can facilitate the energy and digital transitions of the parties involved, as the green transition and the emergence of cutting-edge technologies restructure production schemes.

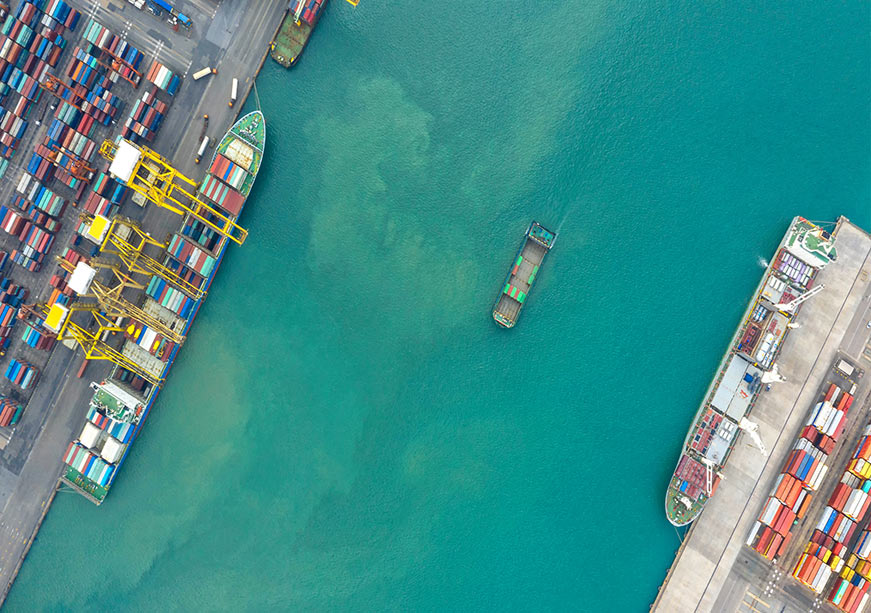

As a consequence of these geostrategic and geoeconomic objectives, IMEC has been conceived as a multi-modal project with several complementary dimensions aimed at enhancing and facilitating both physical and digital connectivity. Therefore, the project’s implementation encompasses the construction and integration of maritime and land-based infrastructure, green hydrogen pipelines, electricity grids and data cables. Building on this rationale, IMEC is not merely a single linear commercial pathway between continents, but a network of strategic corridors[3] designed to create a web of resilient and diversified supply chains across different geographies.

Beyond Maritime and Land-Based Entry Points: Strategic Routes to the Hinterland

IMEC’s network character and its potential to serve as a structure for strategic interconnections are underpinned by its predicted integration into existing or under-deployment transport corridors. The latter would entail that the connectivity project’s scope and outreach are more extensive than the strictly delimited geographic area of its trajectory. As such, the maritime entry points could serve as strategic gateways to connectivity networks towards the hinterlands of different regions. One notable example might be the connection of multiple economic hubs within the EU’s territory, located at a considerable distance from the original pathway, to the Corridor’s ecosystem[4]. This would also allow landlocked countries without direct maritime access to the Mediterranean to benefit from the corridor’s economic dynamics and commercial flows.

For instance, connecting the Corridor’s Mediterranean segment with the planned Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T)[5]—expected to be deployed in three phases with a core (by 2030), an extended (by 2040) and a comprehensive (by 2050) network component—can scale up the project’s connectivity potential. TEN-T’s logic strongly correlates with IMEC’s as it is also conceived as a “multimodal, and high-quality transport infrastructure”, but with a merely European scope. TEN-T “comprises railways, inland waterways, short sea shipping routes and roads linking urban nodes, maritime and inland ports, airports and terminals”. The integration of these two cross-border connectivity ecosystems—subject to infrastructural adequacy and regulatory— facilitates and accelerates commercial exchanges from the Indo-Pacific to the Euro-Atlantic economic zones, throughout the EU’s hinterland.

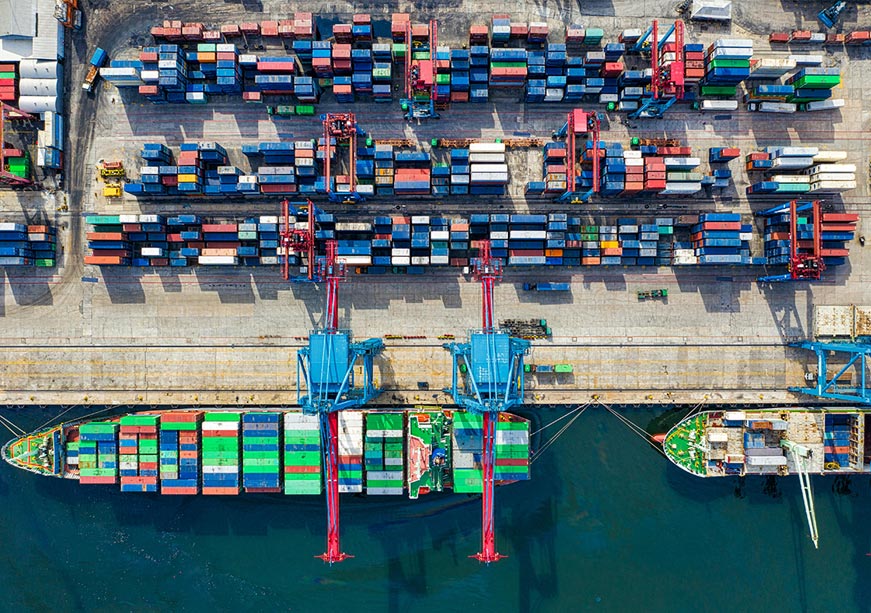

Multiple ports have the potential to link IMEC’s Mediterranean segment to the EU’s inner regions and become the Union’s southern gateways, such as Marseille (France), Piraeus (Greece) and Trieste (Italy). Each port offers strategic advantages considering its specific geographic location and proximity to different EU regions and maritime areas. Considering its substantial weight within the European industrial and manufacturing sectors, a region that’s integration into the corridor’s ecosystem might be of particular importance is Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). With the integration of the majority of the CEE countries into the European Union in the early 2000s and 2010s, this region has become an essential economic centre and “the industrial heartland of Europe[6]”. From this perspective, Trieste, the “northernmost harbour of the Mediterranean Sea”, could become a strategic IMEC gateway for the CEE region. As Italy’s IMEC Special Envoy, Ambassador Francesco Talò highlighted, this port has traditionally been “the harbour of Central and Eastern European countries”, as the closest Mediterranean access to their production centres.

Trieste is a connectivity hub; it is located “at the intersection between shipping routes and the Baltic-Adriatic and Mediterranean TEN-T core network corridors”. It has railway connections to the manufacturing and industrial areas of North-East Italy and Central Europe”. Thus, recognising Triest’s geostrategic and geoeconomic assets and leveraging the port as IMEC’s sub-regional gateway to Central and Eastern Europe can contribute to the development of a more extensive web of multi-regional supply chains and commercial pathways. The latter could extend from the Baltic-Black-Adriatic seas triangle to the Indo-Pacific. Yet, following the logic of access complementarity and diversification, it is worth noting that an IMEC “label” to Triest does not exclude other European harbours from playing the role of sub-regional gateways to other parts of the EU. The effective integration of these ports into the IMEC network will be subject to the economic and financial opportunities the business community sees in these maritime connectivity hubs.

“Team Europe” approach: Leveraging the EU’s potential

Engagement with the private sector to attract and mobilise capital for the development and operationalisation of IMEC’s infrastructure can be facilitated through the Team Europe approach. As defined by the European Commission, the EU and its member states are “joining forces so that our joint external action becomes more than the sum of its parts. By working together and pooling our resources and expertise, we deliver more effectiveness and greater impact”. Considering that the EU itself is a party to IMEC, it can legitimately engage in the project’s implementation with its Member States through a coordinated, joined-up approach. This would allow the European Union as a whole, with its countries, to leverage its economic power of being a single market of over 450 million consumers to attract investments at scale. Accordingly, a first coordination meeting was organised in July 2025 between the EU Directorate-Generals (DGs) overseeing IMEC’s implementation (the DG for the Middle East, North Africa and the Gulf as well as the DG for International Partnerships) and the representatives of the three signatory Member States (Germany, France and Italy). Based on this initial discussion, the engagement with the private sector and the undertaking of feasibility studies have been identified by the parties as shared priorities.

Stemming from this coordinated approach to advance IMEC’s development, the Team Europe setup carries both practical and symbolic importance. It demonstrates to the public and private sector, both within and outside of the Union, that the implementation of IMEC’s European leg is being managed within the EU in a structured and harmonised way. This approach bears the promise of making IMEC the external component and up-scaled extension of the EU’s internal connectivity ecosystem.

Conclusion

The IMEC holds the potential to have an impact extending beyond the scope of its designated geographic trajectory. As the project is multi-dimensional in nature and favours a network structure, even countries that are not part of the core signatories could, in some way, be connected to its ecosystem. For instance, connections between IMEC’s regional entry points and these regions’ hinterlands can be established through dedicated infrastructure hubs, serving as strategic gateways.

Within the EU’s territory, multiple ports are well-positioned to serve this purpose by linking sub-regions to the Corridor. Among them, Trieste is the closest to the majority of the EU’s main industrial and manufacturing centres located in Central and Eastern Europe. Capitalising on Trieste’s strategic location as a hub for external maritime trade and intra-European transport networks, the EU has high potential to integrate significant parts of its production capacity into a multi-regional commercial network. Other European Maritime access points, like Marseille or Piraeus, could unlock additional connectivity opportunities towards different parts of the EU’s hinterland and distant maritime areas. Such a multi-access structure, based on complementarity, could contribute to IMEC’s underlying objective to diversify and secure supply chains and commercial pathways.

To effectively integrate the relevant ports into the Corridor’s ecosystem, the project needs to benefit both from the parties’ political engagement and the business community’s investments. Consequently, private sector engagement has been identified as a priority for the Team Europe structure, bringing together—at this stage—the European Commission and the representatives of the IMEC signatory EU member states. This setup, which promotes a coordinated approach among the European counterparts to the Corridor’s implementation, creates renewed impetus for IMEC’s European leg. The latter is a connectivity segment that could link the Indo-Pacific to the Euro-Atlantic economic zones, throughout the EU’s hinterland. However, this project can only materialise if engagement is sustained and withstands geopolitical hurdles.

Eszter Karacsony is an Associate Fellow and Program Lead in Geopolitics at Observer Research Foundation (ORF) Middle East.

[1] Translated from French to English by the author.

[2] Diplomatic source.

[3] Diplomatic source.

[4] Diplomatic source.

[5] Diplomatic source.

[6] Translated from French to English by the author.