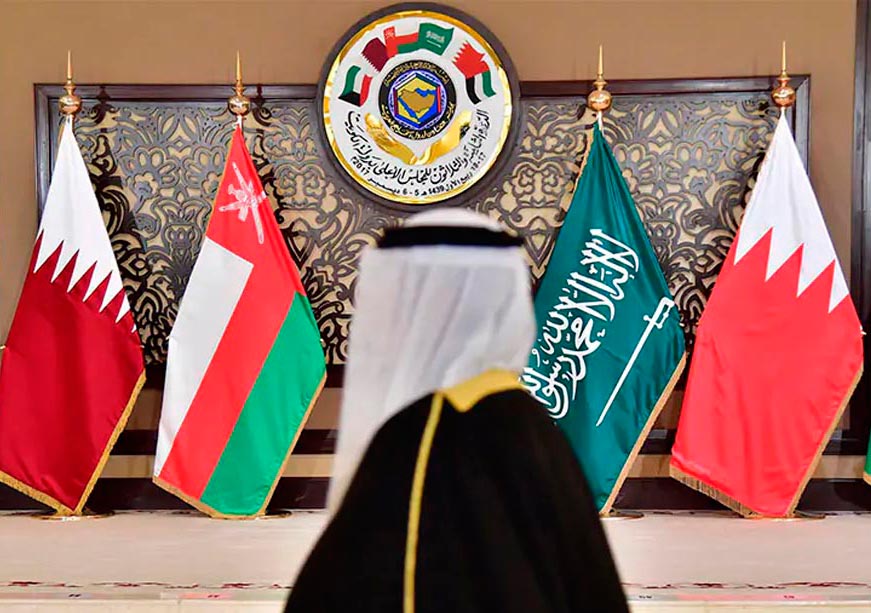

In recent years, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have emerged as active and ambitious players in the global soft power arena. Faced with the twin pressures of economic diversification and geopolitical repositioning, these states are utilising an array of tools to reshape how they are perceived internationally. This brief examines how GCC countries are cultivating soft power across multiple domains and evaluates the effectiveness of these strategies in enhancing their international influence. It analyses both state-driven initiatives and their supporting ecosystems, such as sovereign wealth funds, media platforms, cultural institutions, and development aid frameworks. Through comparative analysis, the brief explores the divergence in soft power trajectories among the Gulf states and identifies which approaches are yielding the most credible global influence. It also offers certain strategic insights for trailing countries within the GCC to enhance their international soft power.

Attribution: Samriddhi Vij, “The Rise of Soft Power in the Gulf: A Comparative Analysis of GCC Strategies,” ORF Issue Brief No. 830, Observer Research Foundation, September 2025.

Introduction

Soft power, a concept introduced by political scientist Joseph Nye in the late 1990s,[1] is often referred to as a country’s ability to influence others through attraction and persuasion rather than coercion or payment. Nye articulated that while hard power relies on military and economic means to compel behaviour, soft power operates through cultural appeal, political values, and foreign policies that are seen as legitimate or morally authoritative.

The foundational elements of soft power are often categorised into three primary resources: culture, political views, and foreign policy.[2] The global appeal of a nation’s culture, encompassing arts, traditions, and popular media, can enhance its attractiveness. For instance, the widespread popularity of Korean music and films has significantly contributed to the country’s soft power.[3] Further, when a nation upholds values such as human rights and the rule of law by aligning its actions with these principles, it bolsters its credibility and influence internationally. Lastly, policies perceived as legitimate and morally upright, particularly those that consider the interests of other nations, can enhance a country’s soft power.[4]

In more recent years, emerging literature also suggests that economic investments can qualify as soft power when they are designed or perceived to enhance a country’s attractiveness, build long-term influence, or foster goodwill, rather than to extract immediate strategic concessions.[5] For countries of the Gulf region, for example—the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Oman, Kuwait, and Qatar—this includes investments by sovereign wealth funds in prestigious international assets (such as sports clubs, universities, or cultural institutions), development financing in the Global South, and infrastructure investments that visibly improve public welfare in recipient countries. These differ from hard power tools like sanctions, military aid, or coercive conditionalities, which aim to compel behaviour.

Soft power investments rely on voluntary attraction; they work best when they are non-threatening, benefit both parties, and are aligned with a country’s broader image as a constructive global player. In contrast, an economic tool becomes hard power when it is used transactionally, such as when aid is tied to diplomatic recognition or investment is leveraged for exclusive access to strategic assets. Ultimately, the distinction lies not just in the nature of the investment, but in the intent behind it and the perceptions it generates.

However, the measurement of soft power presents challenges due to its intangible nature. Traditional metrics have included indicators such as the number of cultural institutions abroad, international students hosted, and global public opinion surveys. Recent advancements have introduced more comprehensive indices. For instance, the Global Soft Power Index (GSPI),[6] which has been released by Brand Finance every year since 2020, ranks 193 nations on 55 metrics of soft power. The index aims to provide a systematic approach to measuring soft power by capturing its multifaceted characteristics across culture, business, and diplomacy, including “strong and stable economy”, “influential in arts and entertainment”, “food the world loves”, and “helpful to countries in need”.

The performance of GCC countries in the GSPI has exhibited notable shifts since its inception, reflecting their evolving international influence and strategic initiatives. The Global Soft Power Index rankings from 2020 to 2025 (see Table 1) reveal distinct trajectories for GCC countries, reflecting their evolving diplomatic, cultural, and economic engagement strategies on the world stage. Most prominently, the UAE rose steadily from 18th in 2020 to a top-10 global soft power rank by 2023, maintaining it through 2025. Saudi Arabia climbed from 26th in 2020 to 18th in 2024, before dipping slightly to 20th in 2025. Qatar improved its soft power ranking from 31st in 2020 to 21st in 2024, before slipping to 22nd in 2025.

| Table 1. Global Soft Power Ranking (2020-25) | ||||||

| Country | 2020[7] | 2021[8] | 2022[9] | 2023[10] | 2024[11] | 2025[12] |

| United Arab Emirates | 18 | 17 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Kingdom of Saudi Arabia | 26 | 24 | 24 | 19 | 18 | 20 |

| Bahrain | Data not available | 65 | 68 | 50 | 51 | 51 |

| Kuwait | Data not available | 42 | 36 | 35 | 37 | 40 |

| Oman | Data not available | 51 | 49 | 46 | 49 | 49 |

| Qatar | 31 | 26 | 26 | 24 | 21 | 22 |

Source: Brand Finance, “Global Soft Power Index”, https://brandirectory.com/softpower

In sum, understanding and quantifying soft power requires a nuanced lens that goes beyond traditional cultural and diplomatic tools to include economic investments that enhance a country’s global appeal and influence. As the Gulf countries increasingly leverage sovereign wealth funds and strategic global assets to shape perceptions and foster goodwill, their trajectories in the Global Soft Power Index reveal how these tools are being deployed, with varying degrees of success. The divergence in rankings among GCC states reflects the effectiveness of their soft power strategies, rooted in foreign policy, political values, cultural outreach, and economic engagement.

Soft Power Pathways for Gulf Countries

The Gulf countries are engaging across all four categories of soft power: cultural appeal, political values, foreign policies, and economic investments. However, each of them has specific strengths. Starting with the UAE, which is the top-ranked Gulf soft power. According to the country’s government data sources,[13] the UAE’s outward foreign investment stock exceeded US$262 billion in 2023, averaging an annual growth rate of 13.4 percent since 2016. It is also the Gulf country with the highest level of outward investment flows since 2022. The conversation around such investments has been amplified through world-class convenings such as the Expo, COP28, and the World Governments Summit hosted by the UAE. While it is likely to maintain this position, Saudi Arabia is another Gulf nation that has seen a steady rise of soft power in the past few years.

Saudi Arabia has been utilising its economic toolkit for soft power, though its approach is complex and multifaceted. The Kingdom’s soft power push is, in part, a strategic necessity to mend an international image damaged by the military intervention in Yemen (2015)[14] and the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018.[15] The Kingdom has been the leading provider of bailout assistance in the Middle East and beyond since 1963, representing[16] around 60 percent of the Gulf States’ foreign assistance in that period, estimated at US$206 billion. Iraq, Egypt, Pakistan, and Syria have been the top recipients of such Saudi assistance. According[17] to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), Saudi Arabia is one of the top five global humanitarian donors in 2025 and has maintained a leading position as a donor from the region for several years. As its sovereign wealth fund,[18] the PIF, is reportedly pivoting to focus more on domestic mega-projects to achieve the ambitious goals of Vision 2030, this internal realignment could have contributed to the decline in ranking from 2024 to 2025.

Qatar is the third-ranked country in the Gulf for soft power, and is particularly known for utilising its foreign policy for such purposes. An important tool for Qatar’s foreign policy is the Al-Jazeera media network, which scholars have identified[19] as a proponent of the state’s political positions. This means that the network has been observed[20] to promote a new brand of pan-Arabism as a mix between political Islam and pan-Arabism. The network was launched in 1996, and a decade later, in 2006, an English-language segment was launched, effectively promoting Qatar’s foreign policy and securing its soft power across global and Arab households.

Qatar has also been engaging in mediation as part of its foreign policy, particularly since the 2007-08 mediation between the Yemeni government and Houthi rebels.[21] Qatar has hosted negotiations for some of the more critical conflicts in the world, including the talks between Hamas and Israel since 7 October, as well as in Afghanistan and Sudan. These are generally complemented by efforts such as the Doha Forum. However, the most high-profile Gulf country that utilises mediation in foreign policy for soft power is Oman. The sultanate is credited with the success of the 2015 Iran nuclear deal and was dubbed[22] the ‘Switzerland of Arabia’ for such efforts. A decade later, in 2025, the Americans and Iranians are in Oman for talks again on securing a deal to calm[23] tensions between them.

In terms of political values, it is the Kingdom of Bahrain that appears to have invested heavily in promoting tolerant and pluralistic values both locally and on the global stage. In 2025, the Kingdom credited[24] itself with the United Nations General Assembly’s adoption of 28 January as the International Day of Peaceful Coexistence. This development was shortly after the Kingdom established[25] the King Hamad Global Center for Coexistence and Tolerance in 2018. This strategy is important as it seeks to mend an international image that was severely affected by the government’s crackdown on the Pearl Square protest movement[26] and its aftermath. Bahrain is also particularly known for commemorating[27] the Shiite Ashura season annually for its local community, and it has made meaningful outreach to the Christian and Jewish communities. Ashura, which marks the martyrdom of Imam Hussein, is a deeply significant event in Shia Islam, symbolising resistance against injustice. By facilitating these commemorations, Bahrain affirms its commitment to religious tolerance and inclusion.[28] According to Rabbi Marc Schneier, Bahrain is the country with the only[29] indigenous Jewish community still in existence on the Arabian Peninsula, which is active in public life. Moreover, as a testament[30] to Bahrain’s positioning on tolerant values, the Roman Catholic pontiff, Pope Francis, now deceased, visited the Kingdom in November 2022, participating in a conference titled ‘East and West for Human Coexistence’.

Lastly, Kuwait is a Gulf country that has invested in its cultural appeal throughout the Arab world. Before its independence, the Al-Arabi monthly magazine was a household name across the Arab world, sharing knowledge and spotlighting[31] Arab culture even before the advent of television. When theatre and television became popular, it was Kuwait that stood out in the Gulf, with its plays and soap operas dominating the cultural scene at large. As a result, Kuwait was named[32] the Arab Capital of Culture and Media for 2025 by the Arab League Educational, Cultural and Scientific Organization (ALECSO), a designation[33] it earned back in 2001. Moreover, Kuwait’s cultural offices abroad host exhibitions showcasing such leadership in the arts and media, with one held[34] as recently as February 2025.

Policy Recommendations for Enhancing Gulf Soft Power

Studying the evolution of soft power across GCC states reveals not only divergent trajectories but also lessons about cost-efficiency, strategic focus, and reputational returns. While strict causation between specific initiatives and Global Soft Power Index rankings cannot be established, the correlation between such investments and shifts in ranking provides a useful lens for analysis.

Value-based diplomacy has proved to be the most cost-efficient tool in comparative terms. Bahrain has made notable gains using relatively low-cost strategies centred on cultural heritage and pluralism. Bahrain registered a 14-place leap from rank 65 in 2021 to 51 in 2024 after its sustained efforts in interfaith diplomacy, including the high-profile papal visit and UN-recognised ‘Day of Peaceful Coexistence’. These results show that targeted, value-driven outreach can yield high visibility without massive capital expenditure.

Further, investments in hosting and mediating are the fastest catalysts for visibility. The UAE’s jump from rank 18 in 2020 to a top-10 global position by 2023, and its sustained ranking at the 10th position in 2024 and 2025, coincides with a string of globally visible efforts like Expo 2020, the Abraham Accords, COP28, and the World Governments Summit. Similarly, Qatar’s soft power rise, from the 31st position in 2020 to the 21st in 2024, has been powered by high-stakes mediation roles (notably in Afghanistan and Israel-Gaza conflicts). Oman, while consistent, remained stuck in the high 40s despite its diplomatic credibility, suggesting that quiet diplomacy without parallel global amplification limits momentum.

As a result, trailing countries need sharper branding and institutionalisation. Kuwait’s soft power score dipped from 35 in 2023 to 40 in 2025, and Oman showed minor regression after some progress, moving from 46 in 2023 to 49 in 2024 and 2025. These fluctuations suggest a lack of strategic follow-through. Unlike the UAE or Qatar, these states have not institutionalised their soft power agendas through global media networks, world-class convenings, or strategic communications. For such countries, a focused strategy that consolidates soft power identity and invests in supporting infrastructure (like think tanks or cultural centres abroad) is essential to ensure durability.

Saudi Arabia’s soft power journey illustrates the importance of sustained international engagement. The Kingdom achieved a steady ascent from the 26th position in 2020 to the 18th in 2024 by aligning its sovereign wealth investments and humanitarian leadership with Vision 2030. Its subsequent dip to the 20th position in 2025 offers a crucial insight. This slight decline likely reflects the strategic pivot to prioritise domestic mega-projects, suggesting that even a powerful national narrative requires consistent international reinforcement through overseas investments to maintain momentum in the global rankings. This indicates that while scale and structural leverage are key, maintaining high visibility is equally critical.

Therefore, it is key to institutionalise soft power efforts that integrate foreign policy, cultural affairs, political values, and sovereign investment promotion under one narrative strategy through global convenings and outreach.

Conclusion

As the Gulf countries transition from regional to global players, soft power has emerged as a critical lever for shaping international perception and advancing national interests. The UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar have gained ground through strategic investments, event diplomacy, and media influence. However, countries like Bahrain, Oman, and Kuwait are still refining their pathways. It is important to not only understand these divergences but also consider why they emerge.

Going forward, the most sustainable soft power strategies will be those that are consistent and visible, rooted in authenticity, reinforced through institutional coherence, and amplified on the global stage. As the global order becomes increasingly multipolar, the Gulf’s ability to shape perceptions and cultivate trust may prove to be as consequential as its economic heft.

Endnotes

[1] Joseph Nye, “Soft Power: The Origins and Political Progress of a Concept,” Palgrave Communications 3 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2017.8.

[2] Jonathan McClory, The New Persuaders: An International Ranking of Soft Power, Institute for Government, https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/The%20new%20persuaders_0.pdf

[3] Minsung Kim, “The Growth of South Korean Soft Power and Its Geopolitical Implications,” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs (2022), https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/Display/Article/3212634/the-growth-of-south-korean-soft-power-and-its-geopolitical-implications/

[4] “The New Persuaders: An International Ranking of Soft Power.”

[5] Daniele Carminati, “The Economics of Soft Power: Reliance on Economic Resources and Instrumentality in Economic Gains,” Economic and Political Studies (2021), https://doi.org/10.1080/20954816.2020.1865620.

[6] Brand Finance, “Global Soft Power Index,” Brand Finance, https://brandirectory.com/softpower

7 Brand Finance, “Global Soft Power Index.”

[7] Brand Finance, “Global Soft Power Index 2020,” Brand Finance, https://static.brandirectory.com/reports/brand-finance-nation-brands-2020-preview.pdf

[8] Brand Finance, “Global Soft Power Index 2021,” Brand Finance, https://mcy.gov.ae/ar/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2024/08/Global-Soft-Power-Index-2021.pdf.

[9] Brand Finance, “Global Soft Power Index 2022,” Brand Finance,https://mcy.gov.ae/ar/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2024/08/Global-Soft-Power-Index-2022.pdf.

[10] Brand Finance, “Global Soft Power Index 2023,” Brand Finance, https://mcy.gov.ae/ar/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2024/08/Global-Soft-Power-Index-2023.pdf.

[11] Brand Finance, “Global Soft Power Index 2024,” Brand Finance, https://static.brandirectory.com/reports/brand-finance-soft-power-index-2024-digital.pdf

[12] Brand Finance, “Global Soft Power Index 2025,” Brand Finance, https://brandfinance.com/insights/global-soft-power-index-2025-the-shifting-balance-of-global-soft-power

[13] Ministry of Economy UAE, “Open Data,” https://www.moec.gov.ae/en/moec-opendata.

[14] Thomas Juneau, “Saudi Arabia’s Costly War in Yemen: A Neoclassical Realist Theory of Overbalancing,” International Relations (2024), https://doi.org/10.1177/00471178241231728

[15] “Jamal Khashoggi: All You Need to Know About Saudi Journalist’s Death,” BBC News, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-45812399

[16] “Gulf Bailout Diplomacy,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2023, https://www.iiss.org/research-paper/2023/11/Gulf-Bailout-Diplomacy/.

[17] Financial Tracking Service, Total Reported Funding 2025, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2025, https://fts.unocha.org/global-funding/overview/2025.

[18] Hadeel Al Sayegh, Iain Withers, and Anousha Sakoui, “Saudi Wealth Fund to Cut Overseas Investments,” Reuters, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/financial-technology-leaders-attend-saudi-investment-conference-2024-10-29/.

[19] Philip Pherguson and Karim Pourhamzavi, “Al Jazeera and Qatari Foreign Policy: A Critical Approach,” Journal of Media Critiques (2015), https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=496211.

[20] Sam Cherribi, The Symbolic World of al Jazeera (Oxford University Press EBooks, 2017), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199337385.003.0002.

[21] Sultan Barakat, “Qatari Mediation: Between Ambition and Achievement,” Brookings Doha Center, 2014, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/final-pdf-english.pdf

[22] James Worrall, “‘Switzerland of Arabia’: Omani Foreign Policy and Mediation Efforts in the Middle East,” The International Spectator, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2021.1996004.

[23] Jon Gambrell, “Oman to Host Key Iran-US First Meeting,” AP News, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/iran-us-talks-oman-nuclear-program-5813e0814efcd99616428086de6ba0be.

[24] “UN Recognition of International Day of Peaceful Coexistence a Historic Achievement for Bahrain: Journalists,” Bahrain News Agency, 2025, https://www.bna.bh/en/news?cms=q8FmFJgiscL2fwIzON1%2BDknLYSBJpcwSG3CsSOCVDWs%3D.

[25] “King Hamad Global Center for Peaceful Coexistence,” King Hamad Global Centre for Peaceful Coexistence, https://khgc.org.bh/about-us.

[26] “Bahrain crackdown on protests in Manama’s Pearl Square,” BBC News, 2011, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-12755852

[27] “Bahrain Model in Tolerance, Pluralism,” Bahrain News Agency, 2025, https://www.bna.bh/en/ConstitutionalCourttoconsiderConstitutionalCase1/Bahrainmodelintolerancepluralism.aspx?cms=q8FmFJgiscL2fwIzON1%2BDtGb16aspIu5cn6Bh0Q6rcU%3D.

[28] “Bahrain’s Ashura Season: A Testament to Religious Freedom,” Citizens for Bahrain,

[29] Rabbi Marc Schneier, “Bahrain Is a Beacon of Religious Tolerance and Coexistence,” Arab News, 2022, https://www.arabnews.com/node/2188981.

[30] Elizabeth Monier, “Religious Tolerance in the Arab Gulf States: Christian Organizations, Soft Power, and the Politics of Sustaining the ‘Family–State’ beyond the Rentier Model’,” Politics and Religion (2023), https://doi.org/10.1017/s175504832300007x.

[31] Abdullah Al Shayji, “Kuwait’s Soft Power Is Its Biggest Asset,” Gulf News, 2018, https://gulfnews.com/opinion/op-eds/kuwaits-soft-power-is-its-biggest-asset-1.2180201.

[32] “Kuwait Named Arab Culture, Media Capital for 2025 Achievement,” Kuwait News Agency, 2025, https://www.kuna.net.kw/ArticleDetails.aspx?id=3215278&language=en.’

[33] “Kuwait Celebrates as ‘Capital of Culture and Arab Media 2025’ with Panel Discussion,” Times Kuwait, 2024, https://timeskuwait.com/kuwait-celebrates-as-capital-of-culture-and-arab-media-2025-with-panel-discussion/.

[34] “Kuwait Cultural Office in London Unveils ‘Huna AlKuwait’ Exhibition’,” Kuwait News Agency, 2016, https://www.kuna.net.kw/ArticleDetails.aspx?id=3220773&language=en.