Well-preserved forest ecosystems are not just home to a thriving flora and fauna; they naturally protect against climate hazards and sequester carbon, making them strategic tools for climate adaptation and mitigation. However, rising temperatures, forest fires, and commodity-driven deforestation have erased 517 million hectares of tree cover since the 2000s, roughly 37 percent of which is permanent. Despite the renewed focus at COP28 to “halt and reverse deforestation and forest degradation by 2030,” current grants and concessional finance waivers amount to only US$2-3 billion per year, significantly lower than US$130 billion needed annually to protect high-risk forests and meet 2030 Paris Climate and zero deforestation goals.

At COP28 in Dubai, the Government of Brazil proposed the idea of the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF), a multilateral investment mechanism designed to incentivise forest conservation. Ahead of its official launch this November 2025, tropical forest countries (Brazil, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Indonesia, and Malaysia) and their potential sponsors (France, Germany, Norway, the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom) convened through an Interim Steering Committee to shape the TFFF framework.

As developed countries retreat from multilateral commitments and revoke billions in climate finance, an innovative model of sovereign wealth fund for forest restoration spearheaded by tropical forest countries (TFCs) presents a compelling solution. Unlike traditional public grant financing, this scheme offers potentially attractive returns on investment, minimises red tapism and enhances resilience to political turnover. TFFF also aims to provide consistent long-term payments and grants indigenous people and local communities (IPLCs) more autonomy over resource allocation. This could potentially fill the shortcomings of the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility, which struggled due to its lack of predictable, continuous payments and absence of IPLC safeguards.

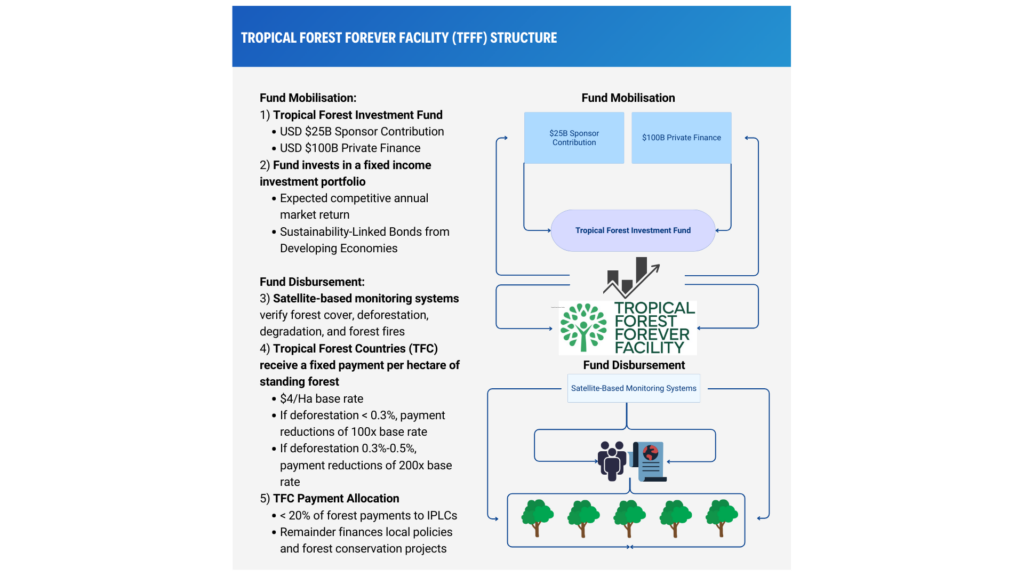

Structure of Tropical Forest Forever Facility

TFFF will likely be supervised by the World Bank with a two-fold structure(—) a Tropical Forest Investment Fund (TFIF) that will mobilise and manage financial resources, and a Tropical Forest Forever Facility that will measure forest cover and determine disbursement criteria.

Under TFIF, sovereign countries and philanthropic investors will make one-time sponsor capital contributions of US$25 billion for the mobilisation of funds. This capital will enable the TFIF to raise an additional USD $100 billion in senior debt from institutional investors. The combined US$125 billion capital base will then be invested in a diversified bond portfolio issued by emerging and developing economies with a focus on sustainability-linked bonds, hoping to generate a competitive annual return.

A portion of the investment returns will be channelled into the TFIF to service the senior debt and sponsor interest, while the remaining amount will go towards TFFF to fund conservation in tropical forest countries. Investors are projected to receive 5.3 percent through the bonds issued by the TFIF. The US$3.4 billion surplus will be distributed to qualifying TFCs that maintain deforestation rates at or below the global average of 0.5 percent. Recipient governments are required to distribute at least 20 percent of the payments to IPLCs who own local forest restoration wisdom and leverage the remainder to support conservation policies and programmes.

TFFF incentivises developing countries to pursue policies that protect standing tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests (TSMBF). Through a clear-cut satellite-based monitoring, verification, and reporting (MVR) system, TFFF will measure changes in forest cover, offering a base rate of US$4 for every hectare of standing forest annually. To discourage deforestation, a tiered discount system was proposed. If a country’s deforestation rate is 0.3 percent or lower, for every hectare of forest lost, the payment is reduced 100 times the base rate. For countries with deforestation rates in between 0.3 and 0.5 percent, it is 200 times the base rate. Overall, TFFF payments are expected to triple the current international non-reimbursable forest finance levels.

Author’s graphic based on information in TFFF Concept Note Version 3

How TFFF Fits in the Forest Financing Landscape

TFFF complements existing programmes such as the Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+). While REDD+ rewards reduced carbon emissions from averted deforestation through carbon credits, TFFF compensates for maintaining and restoring standing forests, thus allocating value to a broader range of ecosystem services. TFFF funding is not tied to individual projects with specific completion timelines. Rather, it fosters a long-term and holistic approach with straightforward monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV), helping overcome factors that hindered the effectiveness of carbon market mechanisms. For instance, emissions leakage where reforestation in one area shifts deforestation to another; the challenge of additionality, which requires justifying that forest protection would not have occurred without financial incentives; or permanence that involves the risk of emissions reversals due to future forest degradation.

Other forest finance mechanisms, such as green and resilience bonds, debt-for-nature swaps, and IPLC-led instruments, come with their own caveats. Green bonds tend to be incorporated in larger blended finance instruments that prefer lower-risk renewable projects. While debt-for-nature swaps for reforestation are often too small relative to the debt size, IPLC instruments funded by NGOs are burdened by excess administrative requirements. TFFF addresses many of these concerns by prioritising IPLC involvement and limiting extensive MRV guidelines.

Challenges and Considerations

Although still a novel mechanism, TFFF will have to overcome a series of financial and social inclusion hurdles to unlock success. Below is an evaluation of the potential challenges and considerations associated with the launch of TFFF.

- Mobilising the First Tranche of Funding: TFFF’s initial takeoff hinges entirely on its ability to successfully mobilise the US$125 billion in capital and generate consistent returns. Although TFFF has gained support from TFCs, investors, and civil society organisations, the risk of not securing the first tranche is high, especially after climate finance shortfalls from last year’s COP. This could delay implementation and undermine confidence in TFFF’s long-term viability. To mitigate this risk, the Government of Brazil has developed a capitalisation strategy with other stakeholders. If TFFF fails to secure sufficient capital, it can still proceed with lower payments. Further, the overall structure of TFFF requires revision and streamlining from a commercial standpoint. Otherwise, funding will likely be entangled in the early mobilisation stages, risking a failure to reach TFCs and IPLCs.

- Market Volatility and Payment Inconsistency: Although projected annual returns are feasible, potential market fluctuations may threaten payment consistency, leading to unreliable donor funding that TFFF was designed to avoid. Investors are expected to absorb early losses, but TFCs may subsequently experience payment reductions. Since forest hectares are already valued quite low at US$4/ha, additional steep penalties would render a net-negative return for TFCs, disincentivising their participation. Compounded with the newest eligibility criteria requiring a minimum canopy threshold, TFFF risks reinforcing uneven climate finance flows.

- Redirecting Capital Away from Deforestation-Linked Sectors: An overarching challenge lies in redirecting private finance away from deforestation-linked sectors. In 2024, 150 financial institutions contributed nearly US$9 trillion to the deforestation economy. To attract investors, TFFF will have to demonstrate equally lucrative returns. Without stronger safeguards, financial commitments, policies or consumer advocacy to shift economic incentives, capital market mobilisation for tropical forests will continue to lag.

- Ensuring Equitable Participation, Funding, and Rights Recognition for IPLCs: Currently, IPLCs struggle with limited visibility in governance and face competition with extractive industries. Although they hold and manage nearly half of the world’s land, they legally own over 11 percent. This disparity is significant because a quarter of global tropical forest carbon is stored on IPLC-inhabited land, and tenure security is strongly linked to better environmental outcomes. TFFF has distinguished itself as a mechanism seeking to establish equitable partnerships with IPLCs. The latest concept note introduced a dedicated financial allocation, rendering countries that fail to transfer at least 20 percent of funds to IPLCs after one year ineligible for payments. Despite progress, this allocation remains unbalanced, with national governments retaining the funding majority. TFFF has an incentive to further strengthen IPLC engagement since COP30 hopes to spotlight their roles and should consider increasing the funding share for IPLCs. The fund should also institute safeguards to prevent investments from unintentionally undermining IPLC land claims and include transparent financial disclosures.

Opportunities for Success

For TFFF to “build a forest-positive economy”, it must reorient the global economic system to value the triple bottomline of prioritising social equity, environmental sustainability, and financial viability, while preventing overexploitation of natural resources by incentivising policy shifts. TFCs can leverage the 80 percent share of flexible government funding to capitalise on the policy momentum from REDD+ and support economic diversification away from forest-depleting industries. This includes investing in alternative livelihoods that are conservation compatible or piloting a conservation basic income scheme that parallels poverty-alleviation cash-transfer programmes by providing consistent and unconditional cash payments to those in forested areas, ultimately reducing dependence on resource extraction.

If TFFF can iron out the aforementioned concerns, successfully mobilise and deploy the capital, it has the potential to reshape global forest finance. Nevertheless, TFFF is not a silver bullet. Its success will require balancing national sovereignty and flexible decisions with strong accountability to protect IPLC rights and tackle the economic drivers of tropical deforestation. With COP30 quickly approaching, TFFF can seize this opportunity to prove that achieving a forest-positive economy while empowering IPLCs is possible.

Leigh Mante is a Junior Fellow, Climate and Energy at ORF Middle East.