Energy, technology and policy drive New Delhi-Tokyo collaboration

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s embrace of Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin in the northern Chinese port city of Tianjin on Monday — his first visit to China in seven years — is getting a lot of attention, and rightly so.

The cordial atmosphere and optics sent a clear message to Washington: India won’t be bullied by the Trump administration or given an ultimatum on trade or security.

But Modi’s visit to Tokyo the week before was, arguably, more productive when it came to high-level cooperation. It was reported that the two countries “agreed to significantly ramp up cooperation in a number of areas, including trade, security and people exchanges.”

As geopolitics in the Indo-Pacific shifts, energy has become central to how India and Japan define their partnership. Rising demand in South Asia, Japan’s search for secure alternatives and the shared urgency of decarbonization have made energy cooperation a test case for whether the two democracies can align climate goals with economic security in an uncertain global order.

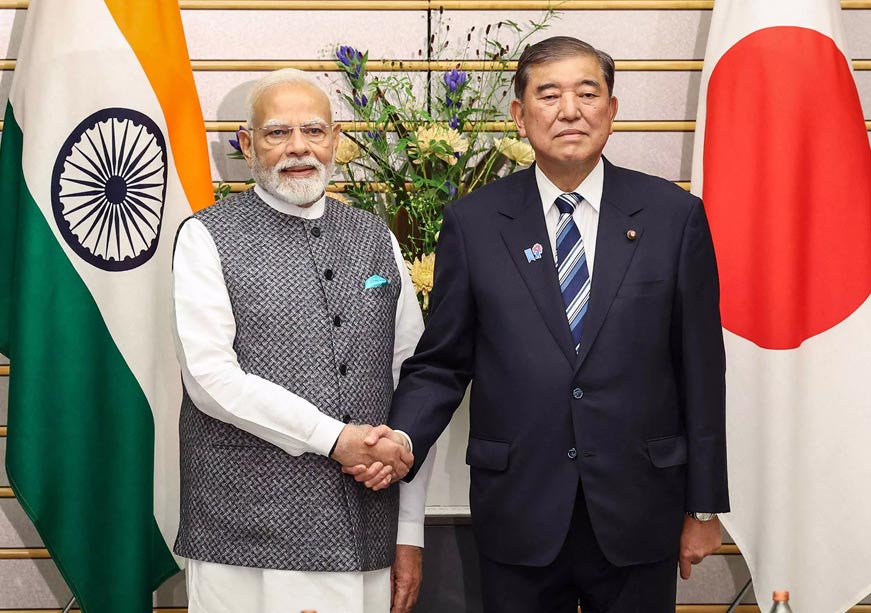

Modi’s Aug. 29-30 visit to Tokyo, where he met with Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, came on the heels of the 11th India-Japan Energy Dialogue, held on Aug. 25. Co-chaired by Manohar Lal, India’s minister of power, and Yoji Muto, Japan’s minister of economy, trade and industry, the meeting reaffirmed a longstanding framework that dates back to 2006.

This institutional base was expanded in 2022 with the India-Japan Clean Energy Partnership, which created sectoral working groups on clean fuels, efficiency and resilient supply chains.

As two of Asia’s largest carbon emitters after China, both governments know that energy cooperation cannot remain rhetorical. Progress so far has been modest but not negligible. The challenge is to build on these frameworks, scale them up dramatically and align projects with the urgency of climate commitments and the realities of energy security.

Within the energy sector, delivery has been visible, though limited in scale. Since 1958, through Official Development Assistance, Japan has extended loans worth more than ¥1.5 billion to safeguard India’s energy availability.

Its financing has supported 14.1 gigawatts of projects by fiscal year 2024-2025 across wind, solar, hydro, cogeneration, storage and thermal capacity, only a modest rise from around 9.3 GW a decade earlier. This underlines how longstanding engagement has produced steady but gradual results, not yet transformative in scale.

Meanwhile, the Japan Bank for International Cooperation’s 2024 survey reaffirmed India as the most promising long-term destination for Japanese firms, yet also pointed to falling business planning ratios. While some companies see opportunity, others remain cautious, citing policy uncertainty, legal complexity, underdeveloped infrastructure and execution risks.

Addressing these bottlenecks will require deeper institutional reforms, smoother regulatory pathways and more transparent risk-sharing mechanisms if Japanese capital is to flow at the scale India needs.

Modi’s visit sought to inject renewed political momentum. Japan pledged to invest up to ¥10 trillion in India over the next decade, doubling its earlier 2022 commitment.

Japanese companies already average around ¥1 trillion annually in foreign direct investment and cumulative inflows since 2000 now exceed ¥6.3 trillion ($43 billion), making Japan India’s fifth-largest investor.

Alongside this, project pipelines are beginning to take shape. ACME Group’s partnership with Japan’s MOL will build a green ammonia facility in Odisha, India, capable of producing 400,000 tons annually by 2030, with exports directed to Japanese power and chemical sectors. Hitachi Energy has been selected to deliver a 950-km HVDC transmission system that will transmit 6 GW of renewable energy in India.

Sojitz and Suzuki, working with Indian Oil and local cooperatives, are investing nearly ¥59.4 billion ($400 million) to scale biogas, embedding Japanese technology in rural India while boosting farmer incomes. Entrepreneurs are setting up a green hydrogen Centre of Excellence in Uttar Pradesh, while Toyota and Suzuki are expected to use India as a base to manufacture hybrid and electric vehicles for export to Africa and Southeast Asia.

These initiatives show that Japanese technology, capital and risk instruments are embedding steadily into India’s clean energy landscape. The question is whether this pipeline can expand quickly enough to meet the urgency of the climate and energy transition challenge.

Meanwhile, external pressures are sharpening. The Trump administration’s renewed tariff measures are reshaping global trade flows while China’s dominance over clean-energy supply chains remains a strategic concern. For both India and Japan, this makes resilient, diversified cooperation not just desirable, but essential.

The Modi-Ishiba Joint Vision 2035, unveiled in Tokyo, reflects this reality. Framed around broader economic and security ties, it places energy at the core, from hydrogen and ammonia to next-generation mobility, emissions monitoring and semiconductor resilience. Japan also promoted the Joint Crediting Mechanism, enabling emission-reduction projects in India to generate credits for both countries.

Japan’s financing institutions and technology partnerships could also help integrate gender-responsive planning into just climate and energy transition projects, aligning bilateral cooperation with global equity debates and enhancing both nations’ credibility ahead of COP30, the 30th United Nations Climate Change Conference scheduled for later this year in Brazil.

Energy security in the Indo-Pacific can no longer be separated from energy transition, and India-Japan cooperation is central to both. As Modi’s Tokyo visit shows, the two countries are not starting from scratch. The challenge is to transform steady, incremental progress into scaled, system-wide change.

That change includes expanding renewable and grid infrastructure beyond pilot projects and balancing investments in evolving technologies such as hydrogen, perovskite cells and carbon capture with a sustained push on proven renewables like solar, wind and energy efficiency. The task also means ensuring finance flows faster and with fewer hurdles, while embedding clean-energy transition and gender equity into project design.

If New Delhi and Tokyo can align ambition with delivery, they will not only advance their own climate pledges but also set a standard for resilient, inclusive energy cooperation in the Indo-Pacific.

This article originally appeared in The Japan Times.