While AI promises transformative potential, its escalating water footprint demands urgent attention. Integrating circular water practices into data centre design is essential for balancing innovation with ecological responsibility.

While Artificial Intelligence (AI) holds a world of possibilities in its application, its impact on the environment demands a closer scrutiny to ensure its sustainable use and deployment. Studies have shown that AI data centres produce electronic waste, consume large amounts of water, rely on critical minerals and rare elements, and use massive amounts of electricity. This presents a paradox: as AI’s computing capabilities increase productivity and conserve resources, they simultaneously drive an exponential rise in energy and water consumption. Training ChatGPT, for example, consumes 1.287 gigawatt-hours of electricity, which is almost equal to the annual electricity consumption of 120 American households. Large-scale data centres, on the other hand, are water guzzlers as they require enormous amounts of water during construction and, once operational, to cool electrical components.

These resource-development-community-city tensions are not incidental but inherent to the socio-technical assemblage that sustains AI systems.

In an already water-stressed world, these trade-offs must be carefully examined as data centres have created tension between technological progress and ecological sustainability in many places. For instance, Chile instituted its first National Artificial Intelligence Policy in 2021, updated in 2024, to transform the country into a ‘global hub’ in the Southern Hemisphere by attracting technology investments to overcome digitalisation and sustainability challenges. In 2019, Google proposed constructing a second data centre in the Cerrillos municipality of Santiago, Chile, with an investment of US$200 million, designed to extract 169 litres of water per second to cool its servers. The project faced resistance from the local community, demonstrating how AI-led infrastructure expansion can intersect with everyday lived experiences and climate extremities, including drought, groundwater depletion, and chronic water inequality.

These resource-development-community-city tensions are not incidental but inherent to the socio-technical assemblage that sustains AI systems. As Bruno Latour argues, the AI ecosystem is a hybrid assemblage of servers, algorithms, minerals, water, workers, energy grids, and ecosystems functioning together as co-constituting agents. The ecological footprint of AI, therefore, is a direct expression of the heterogeneous network it mobilises and not a side effect. The important question is how to align the growth of AI and its resource demands with planetary boundaries and current ecological contexts.

AI and Water Consumption

The water footprint of AI extends to three areas: i) on-site data centre cooling, ii) electricity generation, and iii) semiconductor manufacturing. Typically, electricity generation followed by cooling accounts for the largest share of water use by AI. A comparative evaluation of the water consumption of Llama-3-70B and GPT-4 in 11 African countries found that generating a 10-page report with Llama-3-70B consumed about 0.6 litres of water, while generating the same report with GPT-4 consumed about 53 litres. With 33 percent of the global population still offline, this demand is expected to increase in the future.

It is also important to consider how such water demand and consumption affect region-specific water geographies, as the value of one litre of water varies by location depending on prevailing levels of water stress.

AI-related water consumption also varies with season and the time of day. Research shows that water consumption is 23 percent higher in the summer than in the winter due to increased cooling demands. Overall, this water demand is on an upward trajectory. For example, Google’s data centres consumed 5.6 billion gallons of water in 2023, a 24 percent increase from 2022. These data centres house thousands of servers that run 24/7, generating immense heat and risking failure from overheating if not adequately cooled. In 2022, cooling issues during a heatwave in the United Kingdom forced a shutdown of Google and Oracle data centres in London. Amazon, meanwhile, has more than 100 data centres worldwide, each with 50,000 servers to provide cloud computing services.

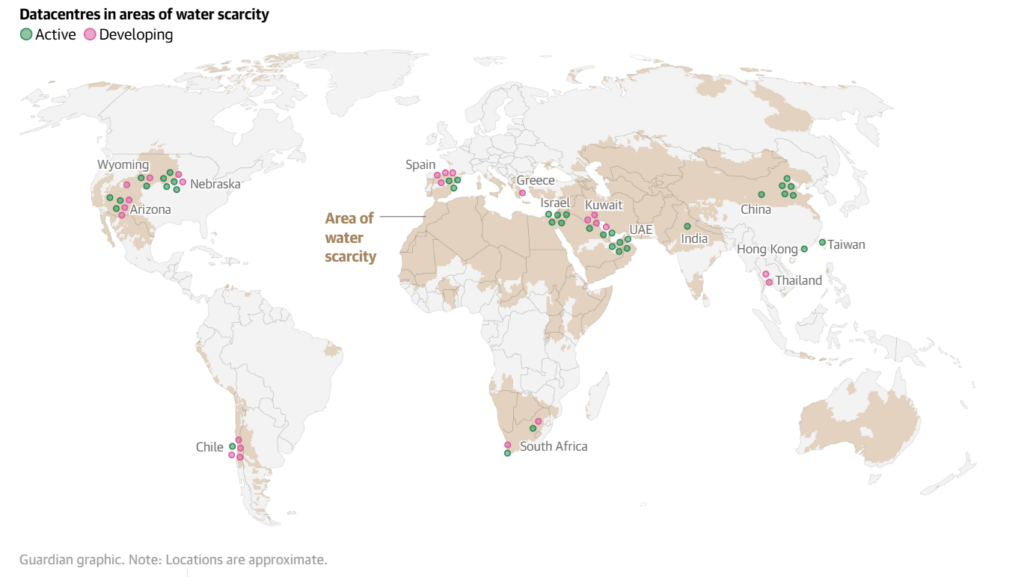

It is also important to consider how such water demand and consumption affect region-specific water geographies, as the value of one litre of water varies by location depending on prevailing levels of water stress. Figure 1 below shows that most data centre hubs are being built in regions already facing water scarcity, drought, flooding, and declining water quality. For example, although Caucaia, a city in northeast Brazil, is water-stressed, tech companies have set up data centres there due to its strategic location near international undersea data cables.

Figure 1: Data Centres in Water-Stressed Regions

Source: The Guardian

India’s projected data centre construction boom, driven by digitalisation, cloud adoption, and initiatives such as the Data Centre Policy, is expected to put further pressure on basic infrastructure in an already water-stressed country. Megacities, including Mumbai, Chennai, and Hyderabad, are already grappling with climate vulnerability, water shortages, and competing domestic and industrial water demands. The expansion of water-intensive digital infrastructure in such sensitive hydro-ecological contexts reflects a structural imbalance and raises concerns about the ecological externalities of digital transformation.

Pathways Towards Circularity

Recognising the ecological footprint of AI, the European Union and the United States (US) have begun introducing legislation to address these challenges, although such policies remain exceptions rather than the norm. Approximately 80 percent of the water used in data centres evaporates, while the remainder is discharged into municipal wastewater systems. This presents significant scope for water reuse and for embedding circularity within the AI water ecosystem to minimise its overall water footprint.

In Washington state, US, Microsoft and the City of Quincy have collaborated to construct the Quincy Water Reuse Utility to treat discarded cooling water from data centres for reuse, thereby reducing the pressure on potable water sources. A similar approach is deployed in Douglas County, Georgia, where Google uses municipal wastewater to cool its data centre. Similarly, 20 Amazon Web Services (AWS) data centres use treated wastewater for their cooling, with plans to expand this practice in more than 120 locations across the US by 2030.

Approximately 80 percent of the water used in data centres evaporates, while the remainder is discharged into municipal wastewater systems. This presents significant scope for water reuse and for embedding circularity within the AI water ecosystem to minimise its overall water footprint.

In some places, on-site rainwater harvesting can supplement cooling needs while reducing stormwater runoff. Discarded cooling water from data centres can also be used for irrigation. Meta, for example, has invested in water infrastructure that allows spent cooling water to be used to irrigate non-edible crops in Idaho, US. Similarly, Denmark’s Odense Data Center uses outdoor air for cooling through indirect evaporative cooling technology. It uses the residual heat to warm local settlements. After cooling the servers, the heated air is used to heat water via water coils, connected with the district’s heating network, reaching the local community. This heat recovery infrastructure has the capacity to recover 100,000 MWh of energy per year, enough to warm 6,900 homes.

These examples demonstrate that embedding circularity into the AI ecosystem is feasible and necessary. Studies have found that in areas where practices such as closed-loop cooling systems, wastewater reuse, and rainwater harvesting are implemented, potential freshwater savings of 50-70 percent are feasible. While such initiatives are largely concentrated in high-income geographies, they illustrate the possibilities for global scale-up.

Conclusion

Water, energy, and computing, today, are interlinked systems — interdependent, dynamic, and vulnerable. A systems-thinking approach is needed to govern this complex reality. To ensure sustainability, the relationship between water and AI must be envisioned as inherently reciprocal. On the one hand, minimising the water footprint of AI infrastructure through smarter, circular, and efficient use of resources is a non-negotiable imperative. On the other hand, AI’s analytical and predictive capabilities must be leveraged for data-driven decision-making to address water crises and governance challenges. Balancing technological progress with environmental stewardship and water conservation is an imperative, as it intertwines with our digital futures.

This commentary originally appeared in Observer Research Foundation.