Iran’s recent decision to drop India from the Chabahar-Zahidan railway line project has been the subject of some consternation in Indian strategic circles. The development has generated disquiet in New Delhi, where some have questioned the timing of the move by Iran. As Indian observers see it, the railway line was part of a strategic endeavour: the development of Chabahar port and an associated rail-links to circumvent Pakistan and its traditional obstruction of India’s overland routes into Central Asia and Afghanistan. Amidst US sanctions, as Delhi searched for suppliers and funding, Tehran suddenly (and unilaterally) decided to go it alone. Oddly, this comes at a time when China has made itself available to assist in the project.

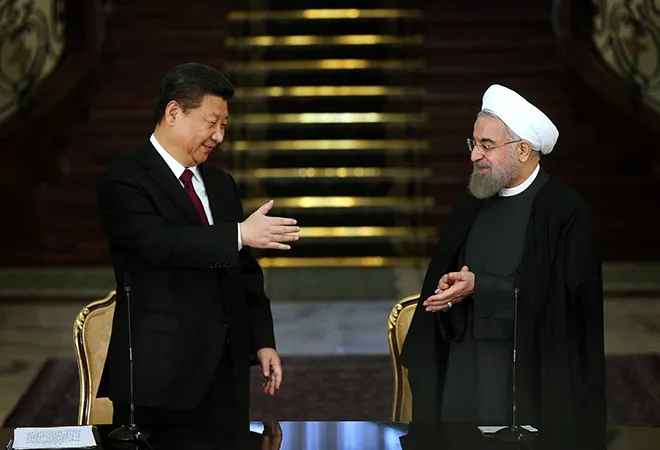

More worrying for Indian watchers is the prospect of a comprehensive military and trade partnership between Iran and China. Beijing, ostensibly, has undertaken to invest $400 billion in key sectors of Iran’s economy, in return for an assured supply of Iranian fuel for the next 25 years. The proposed investment is the biggest China has ever pledged to any country as a part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and envisages huge expenditure in building Iran’s oil and gas and infrastructure sector ($280 billion and $120 billion respectively). Beijing also plans to station over 5,000 Chinese security personnel to protect the investments in Iran.

The implications of a China-Iran strategic partnership are particularly stark in the maritime arena. According to a leaked 18 page draft agreement, parts of which were published by the New York Times last week, Chinese construction companies are set to initiate multiple infrastructure projects along Iran’s Gulf coastline, including free-trade zones in Abadan, a city on the eastern bank of the Shaṭṭ Al-ʿArab River, and on the island of Qeshm, where Tehran is planning a major hub for oil production and storage. China will also build infrastructure at Jask, a port city just outside of the Strait of Hormuz, only 250 miles away from Gwadar, where a Chinese company has already developed and operating a port. Observers say a rudimentary Chinese naval presence at Jask could lead to greater joint military training and exercises between Iran, China and Pakistan, enhancing China’s regional security profile.

China will also build infrastructure at Jask, a port city just outside of the Strait of Hormuz, only 250 miles away from Gwadar, where a Chinese company has already developed and operating a port. Observers say a rudimentary Chinese naval presence at Jask could lead to greater joint military training and exercises between Iran, China and Pakistan, enhancing China’s regional security profile.

To be sure, there is no cause for alarm yet. It is worth noting that the Iranian Revolutionary Guards navy (IRGCN), that is responsible for the waters of the Gulf, is opposed to any foreign naval presence at Iranian ports. The IRGCN controls the Imam Ali naval base in Chabahar, and also has a presence in Bandar-e-Jask and the island of Qeshm. An armed force of radicalized cadres loyal to Iranian Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, the Revolutionary Guards’ Corps has a two point agenda: to protect the revolution and counter the United States. The IRGCN, that uses asymmetric tactics to harass the USN in the Straits of Hormuz, has been instrumental in keeping foreign military activity in Iranian ports to a minimum, and there have been no foreign bases on Iranian soil since 1979. As much as the Iran-China pact creates possibilities for greater Chinese influence in Gulf region, analysts say the IRGC leadership is unlikely to allow a substantial PLA presence in Iranian ports.

In the wider context of Western Indian Ocean region, however, the China-Iran agreement has greater significance. The PLA, which already possesses base in Djibouti, has been gradually expanding its military footprint on Africa’s Eastern seaboard, and in the Northern Indian Ocean. A comprehensive strategic pact with Iran, analysts posit, could allow China to establish military presence along the Iran-Pakistan coastline; the PLA could even assist in the creation of a surveillance network to monitor US and Indian naval activity in the region. With the benefit of Chinese support, and an oil terminal outside the Hormuz, Iran could also be emboldened into adopting a more aggressive stance inside the Persian Gulf.

A comprehensive strategic pact with Iran, analysts posit, could allow China to establish military presence along the Iran-Pakistan coastline; the PLA could even assist in the creation of a surveillance network to monitor US and Indian naval activity in the region.

Notwithstanding the abundant caution the PLAN has displayed in the Gulf region so far, there has been an uptick in Chinese naval engagements with Iran and other regional states. Last year, the PLAN held a trilateral exercise with Iran and Russia, signalling a desire for greater presence in the Northern Indian Ocean. If Iran builds a permanent base in the Indian Ocean, as announced by the head of the IRGCN last year, analysts say Chinese warships could well be frequent visitors at the facility. A proposed a tie-up between Gwadar and Chabahar, could exacerbate India’s predicament. For the Indian navy, already troubled by the China – Pakistan maritime nexus, the development of China-Iran naval ties isn’t good news

Expectedly, many in New Delhi are blaming the United States for the dip in Indian fortunes in Chabahar. The crisis of faith in India-Iran relations, they aver, could well have been avoided had Washington not systematically alienated Tehran. As US sanctions have forced India to reduce its oil imports from Iran, Tehran has lost faith in New Delhi as a reliable partner. What is more, pressure from the Trump Administration has forced the Iranian government’s hand in ways that have hurt Indian interests.

As US sanctions have forced India to reduce its oil imports from Iran, Tehran has lost faith in New Delhi as a reliable partner. What is more, pressure from the Trump Administration has forced the Iranian government’s hand in ways that have hurt Indian interests.

This also highlights a contradiction in India’s maritime relationship with the US: it’s a relationship that works well in the Eastern Indian Ocean, where Indian and American interests neatly align, but is somewhat constrained in the Western Indian Ocean, where there is a divergence of perspectives. Importantly though, New Delhi’s strategic interests are “weighted west”: the oil flows are from west, the bulk of trade is west, as is the diaspora, and India major investments. Not only are India and the US badly coordinated in the Western Indian Ocean, observers say Washington’s Iran policy actively impinges on Indian interests.

Policymakers in Washington and New Delhi must, then, recognize the need for better coordination on Iran. Greater Chinese naval presence in the Northern Indian Ocean in coming years raises the prospects of greater instability and elevated tensions in the Gulf region. The USN and IN have every reason to work together in the Western Indian Ocean, synergizing operations to preserve peace, even as they strive to exert strategic influence in the littorals.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________