Tehran’s bid to redenominate its tumbling rial aims to restore confidence, but without fiscal and structural reform, it risks becoming a cosmetic fix.

When the Iranian rial tumbled to a historic low against the United States (US) dollar in September 2025, it was followed by renewed efforts of currency redenomination in Iran. It was an initiative first floated in 2008, but got approved as a bill by the parliament only in October 2025. The implementation timeline for the Majles-approved plan to slash four zeroes from the rial will now move through subsequent legal and administrative steps before rollout.

The success or failure of a currency redenomination is not determined solely by the act of slashing zeros, but by accompanying structural reforms.

Nonetheless, the success or failure of a currency redenomination is not determined solely by the act of slashing zeros, but by accompanying structural reforms. It is crucial to analyse historical precedents, establish the necessary structural requirements for a successful redenomination, and apply this approach to Iran. This nuanced analysis will enable a comprehensive diagnosis of whether the upcoming redenomination will be a foundational step towards economic recovery or simply another chapter in the nation’s long struggle with inflation.

Requirements for a Successful Currency Redenomination

Currency redenomination has been attempted multiple times as a means of controlling inflation. However, historical precedents suggest that redenomination alone is often ineffective. An extensive study by Karnadi and Adijaya (2017) using a World Bank data set concluded that while redenomination can significantly decrease inflation and increase real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, its effectiveness is not guaranteed. The positive outcomes are statistically significant only when certain underlying conditions are met, primarily high government efficiency and political stability. These two meta-conditions can be broken down into five specific, observable pillars that separate successful reforms from cosmetic failures.

The first pillar is fiscal prudence. This is a non-negotiable prerequisite as the state must credibly manage its revenues and expenditure. Hyperinflation is primarily a fiscal phenomenon caused by the government’s excessive spending and the subsequent printing of money to finance that spending. Before dropping six zeros from the lira on 1 January 2005, Türkiye had already driven inflation to single digits under an International Monetary Fund (IMF)-supported stabilisation and fiscal consolidation programme on which the redenomination plan was built.. In contrast, Zimbabwe removed zeros multiple times, but fiscal dominance persisted and hyperinflation returned until the local currency was abandoned. Research indicates that countries that implement redenomination within a credible macroeconomic framework experience significant declines in estimated inflation and increases in estimated real GDP per capita.

Before dropping six zeros from the lira on 1 January 2005, Türkiye had already driven inflation to single digits under an International Monetary Fund (IMF)-supported stabilisation and fiscal consolidation programme on which the redenomination plan was built.

The second important and closely linked precondition is the central bank’s independence. The monetary authority must be autonomous and free from political interference. Argentina’s multiple currency redenominations repeatedly collided with fiscal pressures and political cycles, undercutting its credibility. A notable example of this issue was in 2001, when the central bank governor was replaced for political reasons, undermining the central bank’s independence.

As a third prerequisite, a successful reform must break the public’s expectation of future inflation. Currency redenomination has an important psychological component. Dzokoto et. al. in their research in Ghana found that a change in currency from ‘New Cedi’ to ‘Ghana Cedi’ impacted the public’s perception, with residents reporting that the new currency felt safer and easier to use. This psychological impact of currency usage must be taken into consideration while designing redenomination plans. Brazil launched “The Real Plan” in 1994—a two-stage procedure of substituting the old currency. First, it created a ‘virtual’ unit (Unit of Real Value or URV) to re-quote prices and contracts, breaking backwards-looking indexation. Later, as behaviours shifted, it introduced a new currency in the form of ‘real’. The monthly inflation fell from over 40 percent to roughly 1–3 percent by year-end. Most failed redenominations neglect this psychological component.

Furthermore, the government must be stable enough to sustain painful but necessary reforms over the long term. Policy reversals and political infighting can instantly destroy credibility. Any sign that the government’s commitment to fiscal restraint is wavering will cause the public to lose faith in the new currency, risking relapse. In 2005, Turkey’s reform was backed by a stable policy mix that persisted through several years, reinforcing public and investors’ confidence in the new currency. In Argentina, currency redenomination was unsuccessful in controlling inflation against a backdrop of political instability. With resignations from two Ministers of Economy in 2001 and the governing coalition visibly weakening, stabilisation efforts were impacted. These findings were also replicated in other studies, which revealed that the positive effects of redenomination on inflation and real GDP per capita were statistically significant in countries with higher political stability and government effectiveness.

In 2005, Turkey’s reform was backed by a stable policy mix that persisted through several years, reinforcing public and investors’ confidence in the new currency.

As the final pillar, a country needs a strong external position, steady foreign exchange inflows, and manageable external debt since redenominations are particularly fragile during balance-of-payments stress. Venezuela reconverted the bolívar multiple times in 2008, 2018, and 2021, yet inflation stayed as reserves eroded and dollarisation rose. Successful episodes often pair redenomination with external anchors, such as IMF programmes and market access, to bolster reserves and credibility. Where reserves are thin and foreign exchange hedging capacity is limited, new currencies are more vulnerable to speculative pressure.

Iran’s Preparedness for Effective Currency Redenomination

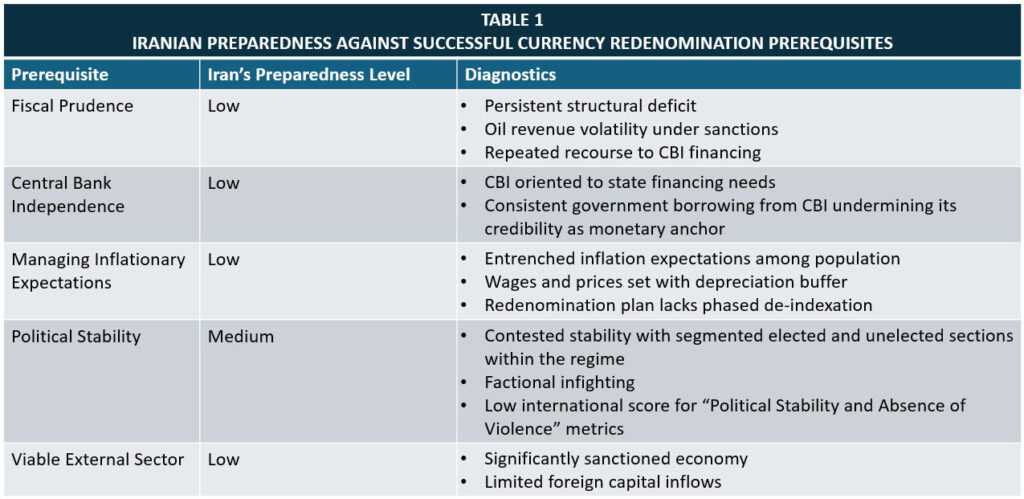

With the five pillars of a successful redenomination established, it is important to analyse Iran’s proposed reform against these conditions. The results of this diagnostic are summarised in Table 1.

First, the Iranian state’s fiscal architecture is the primary driver of its chronic inflation. The budget is characterised by a deep structural deficit and over-reliance on volatile hydrocarbon revenues constrained by a stringent international sanctions regime. Historically, the government has consistently bridged this fiscal gap not through structural reform but through borrowing from the Central Bank of Iran (CBI), a direct monetisation of the national debt. Scarce funds are often channelled into politically favoured projects that distort price signals and crowd out productive private investment. While the Majles has now approved the redenomination bill, there has been no accompanying announcement of a credible fiscal consolidation programme. Without this, the government is merely preparing to remove old zeros while simultaneously creating the conditions for new ones to emerge.

Iran also fares poorly on the Central Bank of Iran’s (CBI) autonomy. It is institutionally subservient to the fiscal demands of the government, with its primary function often being the management of state finances rather than the single-minded pursuit of price stability. Government debt to the Central Bank reportedly increased by 72 percent year-on-year as of June 2024. Without a fundamental and legally ironclad reform of the CBI’s mandate and governance structure, the redenomination will lack a credible monetary anchor.

Formal and informal wages are bargained with an inflation buffer in mind, a pattern visible in recurrent minimum-wage hikes that trail high inflation.

In terms of the third prerequisite of managing public expectations of future inflation, Iran’s unanchored inflationary expectations are a deeply embedded psychological phenomenon. Decades of price instability have created a powerful inflationary inertia that conditions the behaviour of every economic actor. Formal and informal wages are bargained with an inflation buffer in mind, a pattern visible in recurrent minimum-wage hikes that trail high inflation. According to this paper, expected inflation in Iran consistently exhibits a strong positive correlation with the frequency of price changes. Household savings are rapidly shifted into non-real assets such as gold, real estate, and foreign currency. Against this background, the government’s purely numerical redenomination plan can be insufficient. It lacks a sophisticated, phased approach to de-index the economy and break the public’s inflationary expectations before the new currency is introduced. By ignoring this psychological dimension, the reform can fail to address a key driver of persistent inflation.

In Iran, political stability is contested rather than consolidated. The Iranian system integrates an elected presidency with unelected veto centres, such as the Supreme Leader and Guardian Council, which can override policy interests. While the 2024 snap election brought Masoud Pezeshkian to the presidency, Iran has maintained a constant political fabric with Ayatollah Ali Khamenei at its helm. However, even President Pezeshkian has warned that internal infighting poses a greater threat than external enemies, an admission that the political framework remains fragile. Iran’s low international score for the World Bank’s “Political Stability and Absence of Violence” underscores persistent volatility risks. This is compounded by the role of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as a power centre in its own right, delivering a policymaking arena where intra-system rivalries can stall or even reverse the commitments needed for a redenomination to anchor expectations effectively.

The economy is largely isolated from the global financial system due to comprehensive sanctions, which have been exacerbated by the recent snapback of United Nations (UN) sanctions and the US maximum pressure policy.

Viable External Sector is perhaps the most acute vulnerability. The economy is largely isolated from the global financial system due to comprehensive sanctions, which have been exacerbated by the recent snapback of United Nations (UN) sanctions and the US maximum pressure policy. It has severely restricted Iran’s ability to earn hard currency and attract foreign investment. This chronic foreign exchange scarcity means the CBI lacks the firepower to defend the new currency in the open market, leaving it highly vulnerable to the same pressures that have continually eroded the value of the rial.

Ultimately, Iran is preparing to repaint the façade of a building with deep structural cracks. While the new currency may offer a temporary illusion of stability, history shows that such cosmetic fixes are no match for the persistent tremors of fiscal indiscipline, which could leave the nation’s economic future as precarious as it was before.

Samriddhi Vij is an Associate Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation – Middle East.