The spies watched as the Gulfstream jet belonging to the Aviation Research Centre, the aviation wing of India’s foreign intelligence service, the Research and Analysis Wing (R&AW), touched down at New Delhi’s Indira Gandhi International Airport on 30 January 2019. As the “the two ready parcels” on board, Rajiv Saxena and Deepak Talwar, close aides of British arms dealer Christian Miche, stepped off the flight from Dubai to be taken into custody, it marked the culmination of yet another product of Indian intelligence agencies’ burgeoning intelligence cooperation with their Gulf partners.

As India’s strategic interests often increasingly coincide with those of these states in a multipolar age, intelligence cooperation has remained an understudied yet crucial aspect of their partnership.

In recent decades, India has sought closer ties with regional powers in the Gulf, particularly with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia (KSA). As India’s strategic interests often increasingly coincide with those of these states in a multipolar age, intelligence cooperation has remained an understudied yet crucial aspect of their partnership. What, then, are the opportunities and risks associated with India-Gulf intelligence relations? And what might the future hold?

The backdrop

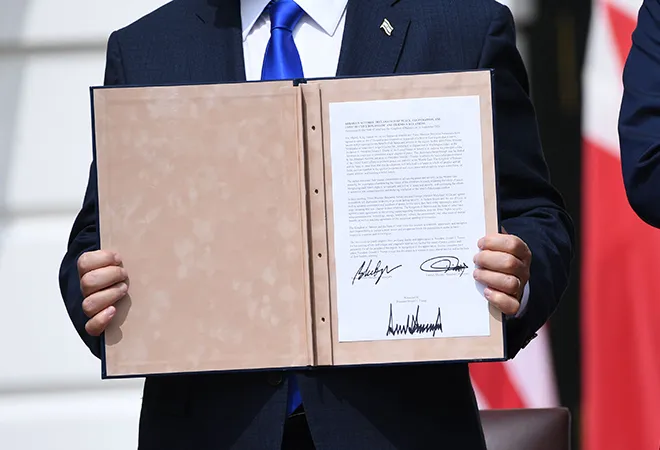

Rajiv Saxena’s case was only one among several others exemplifying the scale of intelligence cooperation between Indian and Gulf intelligence agencies, particularly those of the KSA and UAE. Of the 24 fugitives extradited to from 2010-2018, 18 came from Saudi Arabia and the UAE alone, which is illustrative of the trust apparently defining the partnership between the two sides. This includes names such as Sayyed Zabihuddin Ansari (involved in the planning of the 26/11 attacks in Mumbai and extradited to India from KSA in 2012) and Sabeel Ahmed (extradited from KSA in 2020). Indeed, this cooperation has also extended beyond the Middle East. The arrests of Abdul Karim ‘Tunda’, an LeT recruiter with close links to Dawood Ibrahim, and Yasin Bhatkal the co-founder of the Indian Mujahideen, along India’s porous border with Nepal in the mid-2010s was aided by Emirati intelligence on both counts. Such cooperation is only expected to continue growing with the current upward trajectory of India-Gulf relations, and the signing of agreements such as the one ratified in April 2023 between the R&AW and Saudi Arabia’s Presidency of State Security (PSS) on matters relating to “terrorist crimes and financing”.

As India’s strategic interests become increasingly global in character and ambition, Gulf states help to provide a neutral third-party location for quite clandestine and backchannel diplomacy, even as a need emerges for India to develop backchannels to these states themselves.

Yet the global threat landscape is changing, and with it, so must the strategic foci of India-Gulf intelligence relations. Once a centrepiece of the partnership and the global security agenda, counterterrorism—although still an area of concern—increasingly takes second-place to matters relating to interstate competition, particularly its consequences for supply chain and critical infrastructure defence, and the contest over emerging technologies. India’s strategic investments within the Middle East have also become more entrenched via regional derivatives of its minilateral diplomacy such as the I2U2, emerging in the early 2020s against the backdrop of the Abraham Accords. Moreover, as India’s strategic interests become increasingly global in character and ambition, Gulf states help to provide a neutral third-party location for quite clandestine and backchannel diplomacy, even as a need emerges for India to develop backchannels to these states themselves. Such considerations are increasingly pivotal to India-Gulf intelligence relations, with a discrete appraisal of the opportunities, challenges and solutions emergent from them becoming necessary.

Changing circumstances

The thematic shifts in the contemporary global threat landscape, and their consequences for intelligence activity, have been recognised in both India and in the Gulf- particularly in the UAE and the KSA. Both monarchies have recalibrated their strategic priorities in recent years towards shoring up their ability to serve as individual powers in a multipolar world, creating new ground for convergence with Indian interests, as seen by the latter’s admission into BRICS in late 2023, and Riyadh’s explicit interest in membership.

Joint commitment towards securing supply chains and encouraging regional connectivity in such a strategic environment has also facilitated the planning of economic corridors such as the India-Middle East Economic Corridor (IMEC). A focus on projecting power globally through economic diversification with an emphasis on critical and emerging technologies—Saudi Arabia through investment in smart cities such as NEOM and in the critical minerals sector, and the UAE in the energy sector with an emphasis on new technologies such as green hydrogen—equally remains part of both Gulf monarchies’ arsenal of national security and foreign policy tools to strengthen their ability to act with greater boldness as individual poles of influence in a multipolar world. Multipolarity has also brought with it greater willingness in both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi to normalise relations with Israel in pursuit of grand strategic objectives such as IMEC, with both countries maintaining the likelihood of a resumption of normalisation with Israel upon the termination of its ongoing war in Gaza. In each of these respects, Saudi and Emirati strategic interests coincide with India’s; a consensus that may be realised via a reorientation of existing intelligence cooperation priorities.

Multipolarity has also brought with it greater willingness in both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi to normalise relations with Israel in pursuit of grand strategic objectives such as IMEC, with both countries maintaining the likelihood of a resumption of normalisation with Israel upon the termination of its ongoing war in Gaza.

These emergent areas of national security importance must therefore compel a diversification of intelligence priorities both ways across the Arabian Sea. The sharing of maritime intelligence to secure merchant traffic and supply chains against attacks by actors such as Yemen’s Houthis may be one area of convergence. Existing mechanisms for intelligence sharing, both multilateral such as BRICS, I2U2 or even the SCO, but also bilaterally, may be widened with a focus on financial intelligence (FININT) sharing in view of Riyadh and Dubai’s continuing growth as hubs for international finance. The focus on the private sector in this respect as a zone of intelligence activity may also be expanded, given its position as the primary domain within which threat actors weaponise money flows and launder illicit funds, and whose transparency may lend it to greater compromise by adversary actors.

Counterintelligence challenges posed by this inherent transparency equally relate to the R&D sphere, necessitating greater tripartite cooperation between India, Saudi Arabia and the UAE on issues such as intellectual property (IP) theft. That technologies developed within this space ultimately pervade critical infrastructure and regional connectivity projects, and may be weaponised by hostile strategic actors in the event of compromise, only makes counteracting efforts more crucial. It is therefore recommended that counterintelligence cooperation between the three countries prioritise insulating areas of national security importance from compromise by hostile actors, using a range of human and cyber capabilities and via both offensive and defensive means.

Off-road diplomacy: The Gulf and Intelligence backchannels

With Gulf states diversifying their relations among other regional and extraregional powers, the historic role played by Gulf states as vehicles for clandestine and backchannel diplomacy comes into focus for Indian intelligence agencies. The KSA and the UAE have increasingly grown engagement with Russia, China and even Iran, a longstanding adversary for whom the former has been relaying messages from Washington in view of Israel’s ongoing war against Hamas. Backchannel diplomacy affords both Gulf monarchies the opportunity to play an outsized role in a multipolar world by serving as intermediaries in a range of global conflicts.

The KSA and the UAE have increasingly grown engagement with Russia, China and even Iran, a longstanding adversary for whom the former has been relaying messages from Washington in view of Israel’s ongoing war against Hamas.

New Delhi’s cooperation with KSA and UAE security agencies may therefore come with the expectation and hope that they may help to bolster the continued willingness of these states to facilitate India’s establishment of backchannels with a variety of states, both hostile and friendly. India’s close ties with the Gulf have long enabled New Delhi to conduct quiet, clandestine diplomacy with its adversaries—most notably in January 2021, when it was revealed that the UAE had facilitated talks between Indian and Pakistani security officials in Dubai, despite Islamabad’s subsequent vehement denials.

Yet risks remain. The arrests and sentencing of eight Indian nationals in Qatar for alleged espionage in 2023 illustrates not just the extant challenges in this sphere that the Indian government must account for, but also the need for effective intelligence backchannels to key Gulf powers themselves. Indian intelligence agencies may therefore need to widen their horizons across the breadth of the Middle East and beyond, establishing closer relations with regional intelligence agencies based on their history of either cordiality or neutrality vis-à-vis both India and Qatar. Key contenders may include the intelligence and diplomatic services of Morocco, Oman or Bahrain, among others. Although small, the regional expertise and cordial ties between these agencies and their Gulf counterparts would hold crucial importance were adverse circumstances to arise again in the India-Gulf security dynamic.

Conclusion

India-Gulf relations, although long based upon a shared conviviality, have only taken upon a more visibly ‘strategic’ complexion in recent years, despite the glue binding their security and intelligence partnership—counterterrorism—having waned in the global security imagination lately. Yet the widening of horizons presents new opportunities and challenges for intelligence cooperation in a multipolar age. Greater emphasis on emerging technologies, global financial challenges, and the private sector must come to increasingly define the discourse of the partnership. Likewise, intelligence cooperation may help establish solid foundations for backchannels and clandestine diplomacy, both via and to Gulf powers. Ultimately, a fluid global security landscape does not alter the fundamentals of intelligence cooperation between India and its Gulf partners, but widens the range of opportunities available. It is crucial that we take advantage of them.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Archishman Goswami is a postgraduate student studying the MPhil International Relations programme at the University of Oxford.