With the proven effectiveness of CERN as a valuable tool for scientific diplomacy, the ensuing turbulent geopolitical climate presents an opportune moment for Asia to deploy its own iteration of the organisation

In the post-World War II era, Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire (CERN) emerged as a leader in scientific innovation and research. In the subsequent years, it consolidated its position driven by scientific and technological breakthroughs such as the development of the World Wide Web (WWW) and the discovery of the elusive Higgs boson. Asia, on the other hand, was steadily bolstering its manufacturing capabilities, thereby firmly cementing its place within global technology supply chains in the post-Cold War era.

With Asia’s growing prowess in critical technologies such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence (AI), quantum technology, and nuclear and clean energy, as well as its dominance over critical mineral supply chains that underpin these sectors, it is natural to ask whether the continent is ready for its own iteration of CERN. The answer appears to be yes, though this will require a certain level of cohesion and interoperability among major Asian economies, which is currently lacking.

The Foundational Vision Behind CERN

The idea for the Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire (CERN), also known as the European Council for Nuclear Research, was conceived in the 1940s with the intent of utilising scientific cooperation to help usher in an era of peace, act as a force for unity in a post-war Europe, and simultaneously attempt to inhibit the brain drain of European scientists to the United States (US). In 1953, the CERN convention was signed by twelve member states, which explicitly states its intent: “The Organization shall have no concern with work for military requirements and the results of its experimental and theoretical work shall be published or otherwise made generally available.”

Scientific innovation needs a breeding ground, free from politics and bureaucratic constraints, an idea that informed the creation of CERN and remains central to its success.

Over the next 70 years, CERN has emerged as one of the world’s leading research institutions, particularly in the domain of nuclear and particle physics. CERN began operating the world’s largest and most sophisticated particle accelerator, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), in 2008. The LHC has played a major role in advancing discoveries in particle physics and the Standard Model. The discovery of the Higgs boson, the particle responsible for giving mass to elementary particles, in 2012, remains one of its most significant breakthroughs.

CERN has also driven innovation across fields such as computing, networking, medicine, and data processing, including the invention of the World Wide Web (WWW) by Tim Berners-Lee in 1989, serving as a notable example. Moreover, the organisation has remained aligned with the original intent of the CERN convention. It has established itself as a global hub for scientific innovation while promoting peace and cooperation among its members and partners. It currently hosts 25 member states, alongside associate member states, including Brazil, India, and Pakistan. The organisation maintains international cooperation agreements with non-member states from virtually every continent. CERN’s facilities are utilised by over 600 institutes and universities from around the globe.

Asia’s Emergence as a Global Manufacturing Hub

Being largely driven by the rise of the East Asian Tiger economies in the 1960s, Asian manufacturing took centre stage with the onset of the Third Industrial Revolution. This was further reinforced by the proliferation of digital technologies such as the internet, which led to an industry model pioneered by Silicon Valley, in which manufacturing was offshored to Asian economies, reducing labour and manufacturing costs, thereby achieving economies of scale and maximising profits.

Fuelled by the ideology of globalisation purported in the 1980s, this economic interdependence model played a major role in establishing Asia as a hub for manufacturing. China emerged as a global leader in multiple established and emerging technologies, including semiconductors, AI, quantum technology, and green energy, enabled by strategic planning and government-backed initiatives such as the Made in China 2025 policy. Beijing also dominates the majority of critical mineral supply chains that support these technologies, including rare-earth elements. Moreover, China has been in the process of developing the world’s largest particle collider, the Circular Electron Positron Collider (CEPC).

Taiwan has established itself as the undisputed leader in semiconductor manufacturing, with the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (TSMC) becoming the world’s largest contract chip manufacturer. Japan ranks as the third-largest contributor to global manufacturing output and is a leader in robotics, engineering, and semiconductors on the international stage. South Korea, supported by major chaebols such as Samsung, is similarly a world-leading manufacturing giant in areas such as memory chips and digital electronics.

With the creation of CERN, Europe strategically utilised scientific diplomacy to mend the wounds of the Second World War while promoting regional peace and stability, thereby demonstrating the effectiveness of scientific cooperation as an invaluable diplomatic tool.

Singapore has prospered as a global trade hub, reflecting its ease of doing business and foreign direct investment (FDI) policies. Thailand and Vietnam are emerging as regional logistical hubs, excelling in electronics and semiconductor assembly, testing, marking, and packaging (ATMP). As of 2025, nearly 84 percent of the Philippines’ population is online, indicating a high level of digital connectivity. Indonesia is one of the pivotal nations within the critical mineral supply chains, particularly for nickel and copper mining.

India, while not yet a major manufacturing hub, has exemplified its importance through a service-led approach. India’s approach towards Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI), alongside its indigenisation of space and nuclear technologies, serves as a model for other Global South nations. India also benefits from a massive demographic dividend, which is yet to reach its full potential.

The Strategic Case for an Asian CERN

Scientific innovation needs a breeding ground, free from politics and bureaucratic constraints, an idea that informed the creation of CERN and remains central to its success. However, one of the major drawbacks of CERN has been its focus on pure scientific innovation while being disengaged from technology translation, a cornerstone of the modern world. On the other hand, while Asia’s manufacturing capabilities have certainly been economically beneficial, several prominent Asian nations continue to face a general lack of technological and scientific innovation. Despite its ambition, China’s Circular Electron Positron Collider (CEPC) is facing cost overruns and may not see the light of day without regional cooperation.

The situation creates scope to establish an Asian equivalent of CERN, potentially an ‘Asian Organisation for Scientific Research and Innovation’, which would combine fundamental scientific research with Asia’s strength in technology translation and manufacturing. A focus on semiconductors, AI, quantum technology, and nuclear and clean energy could enable Asian economies to leverage expertise across multiple domains, deepen cooperation, and reduce dependence on Western technology. Asian nations, such as China, Indonesia, Singapore, Vietnam, the Philippines, Thailand, and India—alongside western-backed allies like Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan—could potentially fund this initiative. Given its historical discontent with Western dominance, Russia could also play a role in this endeavour.

Scientific Cooperation as a Mediator for Regional Stability

The gradual shift in the global order has coincided with an increase in conflicts and geopolitical tensions. In the West, this is exemplified by the Russia-Ukraine conflict and the emerging strains in US-NATO relations, as well as the recent American military action in Venezuela. On the other hand, Asia has witnessed escalating tensions in the South China Sea driven by China’s increasing territorial ambitions, whether in relation to Taiwan, the Philippines or more recently, Japan. Moreover, the continent has simultaneously witnessed armed conflicts, including the India-Pakistan and Thailand-Cambodia confrontations. All of this has unfolded amid growing strategic competition between the US and China, which has further escalated regional tensions.

An Asian equivalent of CERN could serve as the nucleus of innovation in the region, promoting ideological diversity and cooperation.

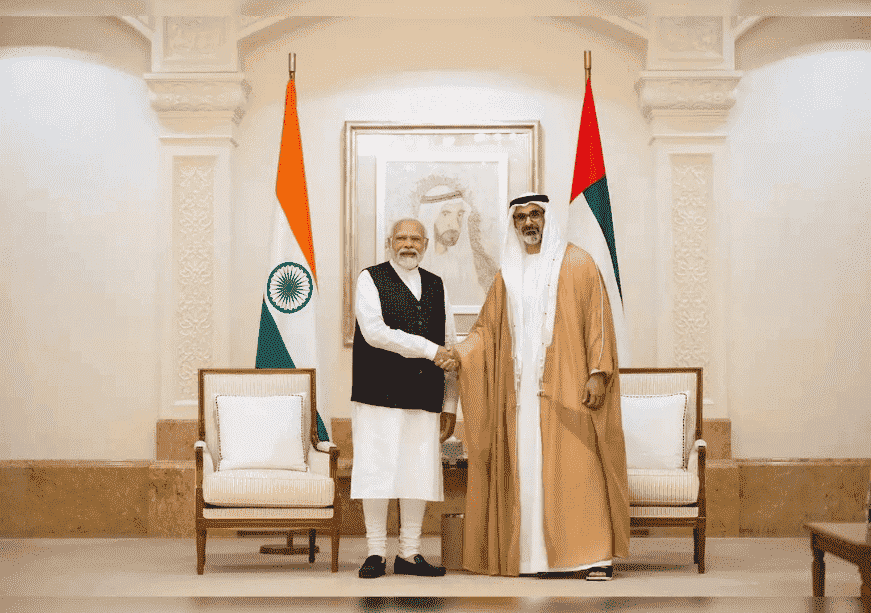

With the creation of CERN, Europe strategically utilised scientific diplomacy to mend the wounds of the Second World War while promoting regional peace and stability, thereby demonstrating the effectiveness of scientific cooperation as an invaluable diplomatic tool. As fissures gradually emerge in the prevailing geopolitical order, an Asian equivalent of CERN could play a similar role by fostering scientific cooperation as a foundation for regional harmony and building a unified Asian front. Scientific diplomacy could also serve as a critical tool for easing China–Taiwan tensions, one of the primary sources of instability in Asian geopolitics. India’s emphasis on strategic autonomy positions it well to lead such an initiative, especially amid its dissatisfaction with Washington’s repeated use of tariffs as a negotiating tool and its relative easing of tensions with China.

Conclusion: Establishing a Culture for Innovation

Human progress has long relied on technological innovation. Rather than remaining hostage to Western policy shifts—including the United States’ turn towards tariffs—Asia has an opportunity to develop its own hub for technological innovation. The continent needs to recognise its immense scientific potential while gradually reducing its over-reliance on Western technological innovation, focusing its efforts on addressing inadequacies while making a committed effort to refine them. An Asian equivalent of CERN could serve as the nucleus of innovation in the region, promoting ideological diversity and cooperation.

Furthermore, an Asian equivalent of CERN can serve as a global message, portraying a unified Asia prepared to overcome its internal disputes and emerge as a leading hub for scientific and technological innovation, surpassing the West in influence. The endeavour could play a significant role in alleviating intra-regional conflict within the continent while also addressing the brain drain dilemma affecting multiple Asian economies, including India, in recent decades. It could ensure that technology fosters human progress and addresses developmental and societal needs rather than being directed merely towards territorial objectives or garnering geopolitical clout.

This commentary originally appeared in Observer Research Foundation.