This year’s COP saw a landmark agreement on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, ending over a decade of negotiations and validating the persistence of carbon trading advocates.

The COP29 unfolded a saga of dramatic events. The Argentinian government withdrew its delegation, while two major developing country groupings—the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS)—staged a temporary walkout, citing exclusion from the negotiation process. India and Nigeria publicly denounced the proposed climate finance deal of US$300 billion a year for developing countries by 2035, falling far short of the US$1.3 trillion a year that was deemed necessary. Adding to the controversy, no consensus emerged over phasing out of fossil fuels neither at the COP nor the G20. All of this played out against the backdrop of another Trump presidency and its concerning implications on global climate action.

Yet, if there is one significant takeaway from this year’s COP29—akin to the landmark agreement on the Loss and Damage Fund at COP 28—it is the groundbreaking new deal on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which governs international carbon trading. The agreement is historic for bringing to close over a decade-long series of negotiations and vindicating the perseverance of carbon trading advocates.

Unpacking carbon trading

The operationalisation of Article 6 is touted to be a significant source of international climate finance and transfer of emerging technologies, crucial for developing countries that often struggle with domestic resource mobilisation to invest in climate mitigation and adaptation projects.

The nitty-gritty of the text is yet to be completed, and the UNFCCC Secretariat needs to iron out pending issues and finalise the details in the upcoming months.

Article 6.2 (Cooperative Approaches)

Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement allows voluntary bilateral or multilateral cooperation among countries or other entities, including companies, for implementing Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) by trading Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs). ITMOs refer to the transferrable units of emission reductions or removals that one country can sell to another to meet its NDC requirements, and the former must make corresponding adjustments in their national emission inventories to avoid double counting of the same emission reduction.

The Secretariat has committed to developing voluntary frameworks and templates for participating countries for authorisation and reporting. The COP29 final text also ignites the debate on the functionality and interoperability of the ITMOs with the Article 6.4 mechanism on an international registry.

Article 6.4 (Centralised Mechanism)

Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement, also known as the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism (PACM), is a successor to the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). It provides a standardised mechanism and a centralised platform to generate and trade emission reduction credits among countries and companies, fostering international cooperation at a global scale to meet climate targets.

Unlike the decentralised governance under Article 6.2, where countries negotiate directly with each other, Article 6.4 has a centralised governance mechanism under a supervisory body which oversees the entire process from project registration to issuance of emission reductions and compliance of reporting guidelines, etc.

The Supervisory Board will be responsible for laying out the rules to ensure regulatory stability and standards on baselines, additionality, suppressed demand, leakage, reversal risk measures and post-crediting monitoring, among others. The text acknowledged issues around the timelines for both—authorisation before issuance and ending CDM operations—while at the same time transitioning CDM projects into the 6.4 framework.

Article 6.8 (Non-Market Approaches)

Article 6.8 of the Paris Agreement defines a framework for non-market approaches (NMAs) through capacity building or concessional/grant funding to promote mitigation and adaptation efforts while at the same time advancing sustainable development goals.

The COP29 text encourages participating parties to utilise and engage with the NMA Platform to support the implementation of NDCs.

Persisting challenges: Transparency, accountability, and additionality

As the standards and methodologies dictating Article 6 are due to be completed by next year to facilitate operationalisation by 2025, the COP29 left several questions unanswered. Primary among them are concerns pertaining to transparency and accountability, which have plagued the carbon trading ecosystem for a long time now, rendering serious reputational and economic challenges. According to a nature study, covering almost one-fifth of the credit volume issued to date and accounting for 1 billion tons of CO2e, less than 16 percent of the carbon credit issued constituted real emission reductions.

Firstly, disclosures are not always mandatory. For instance, countries participating in Article 6.2 do not have to necessarily disclose how they avoid double counting of credits. While the countries are expected to submit an annual report with pertinent details to the UNFCCC, no deadlines or penalties have been specified.

Secondly, the process, timing, and format of authorisation are also unclear. For context, authorisation refers to countries authorising or approving in advance certain mitigation outcomes for international use, whether in bilateral agreements, compliance mechanisms or voluntary carbon markets.

Thirdly, the concern of revoking authorisation after issuance remains. While the text states that any changes to authorisation after the first transfer (mitigation outcome is transferred internationally for the first time to another country or company) will be limited to exceptional circumstances to avoid double counting, it still leaves room for manoeuvring and ambiguity.

Fourthly, tracking across jurisdictions and mechanisms will be a challenge with multiple parallel registries under operation, such as a national registry, an international registry, and a mechanism registry.

Fifthly, there is still an open debate on transitioning CDM projects to the Article 6.4 mechanism and whether the Supervisory Board should review the CDM projects for additional considerations.

Strengthening developing country participation

For countries to truly reap the fruits of the financial innovation offered by international carbon markets, there has to be a strong emphasis on ensuring transparency and accountability in the entire value chain. One of the means to achieve this will be if we can gradually move towards an inter-operational international registry not just across countries but also across mechanisms (Article 6.2, 6.4 and VCM). Such a system will facilitate credit tracking, prevent double counting, as well as harmonise methodologies and standards. This will bring the much-needed certainty and credibility crucial for the success of Article 6.

The Secretariat has been advised to provide optional and additional registry services and support for countries which lack formalised national systems/registries to facilitate their participation in Article 6, including the issuance of credits (ITMOs) and transfer to the international registry (enabling corresponding adjustments where required).

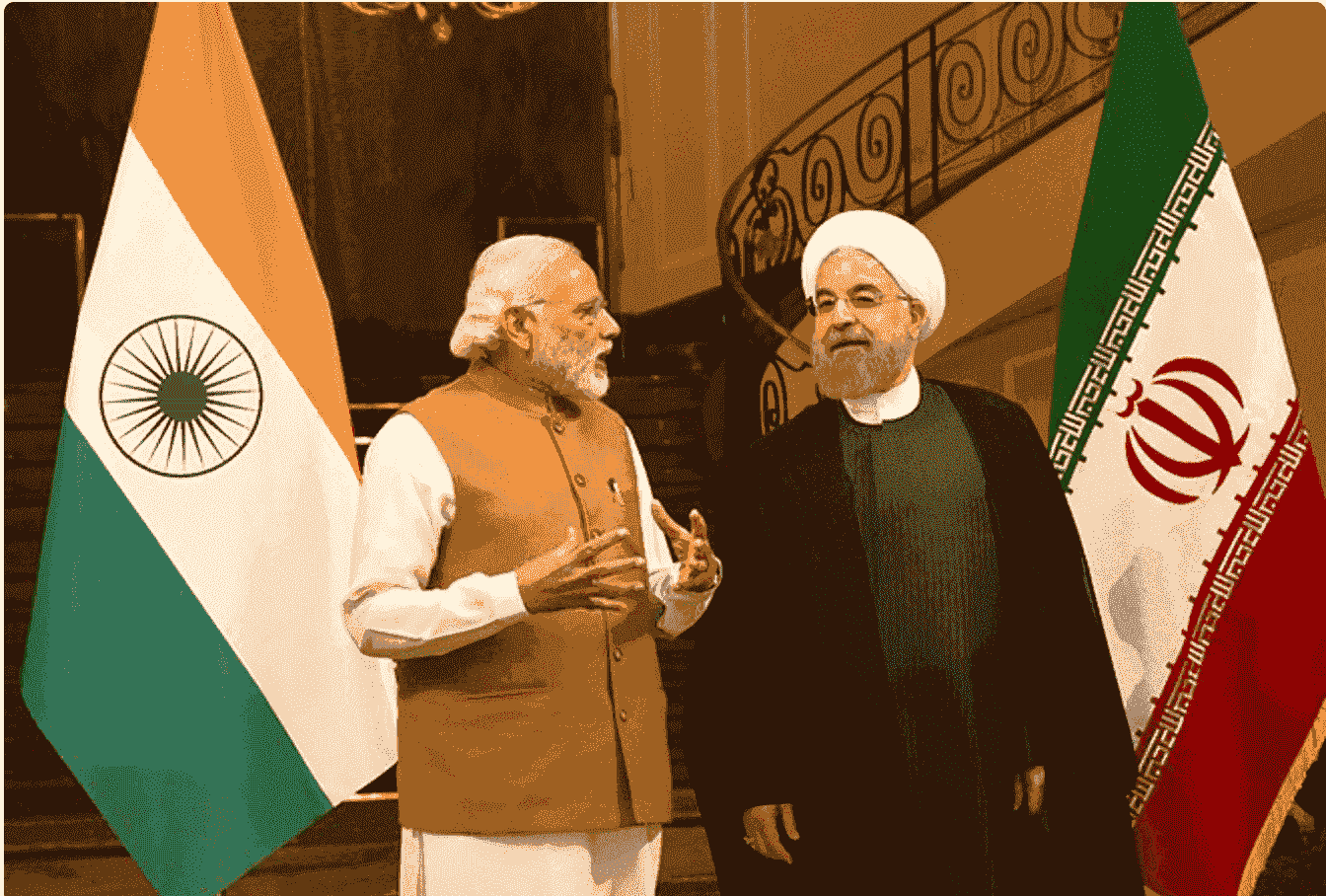

While developing countries like Saudi Arabia and India have cited concerns of national sovereignty owing to over-regulation and data sharing, it is important for these countries to strategically leverage such provisions to their advantage and strike a healthy balance between protecting domestic interest and capitalising from international cooperation.

Another point of reflection is the selection of sectors for authorisation in the international carbon markets. Host countries should be mindful in the sector selection, reserving the low-hanging fruits to fulfil their own Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and opting difficult to fund projects and sectors for funnelling international climate finance. For instance, Ghana aims to issue ITMOs for renewable energy and cooking fuel as opposed to switching light bulbs or planting trees on smallholder plantations, which are cheaper options for the country to manage at its dime

Similarly, for India, solar and wind energy are low-cost options today. India has notified a list of high-cost alternatives, which include 13 activities that may be considered for trading under Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement. More recently, in October 2024, the Bureau of Energy Efficiency also issued a list of approved sectors under the Central Government’s Carbon Capture and Trading System (CCTS) eligible for the Offset Mechanism.

| Mechanism | Activities, Sectors and Technologies |

| Article 6.2 | GHG Mitigation Activities: Renewable energy with storage (only stored component); Solar thermal power; Off- shore wind; Green Hydrogen; Compressed biogas; Emerging mobility solutions like fuel cells; High end technology for energy efficiency; Sustainable Aviation Fuel; Best available technologies for process improvement in hard to abate sectors; Tidal energy, Ocean Thermal Energy, Ocean Salt Gradient Energy, Ocean Wave Energy and Ocean Current Energy; High Voltage Direct Current Transmission in conjunction with the renewable energy projects; Green Ammonia; Carbon Capture Utilization and Storage |

| Offset Mechanism CCTS | Phase 1 1. Energy- Green Hydrogen (through electrolysis); RE with Storage; Offshore Wind; Green Hydrogen production through Biomass; Compressed Biogas; Energy efficiency improvements 2. Industries- Green ammonia usage, feedstock changes in chemical industries. 3. Agriculture- Systematic Rice Intensification; Biochar; Agroforestry 4. Waste handling and disposal- Biochar, Landfill Gas Capture 5. Forestry- Afforestation; Institutional Forestry 6. Transport- Modal Shift; Electric Vehicles/Bus Phase 2 7. Fugitive Emissions- CF4 emission reduction; Recovery and utilization of gas from oil fields 8. Construction-Limestone calcined clay cement (LC3: 9. Solvent use- Industrial solvent reduction 10. Carbon capture and storage of CO2 and other removal- Post-combustion carbon capture technologies |

| Compliance Mechanism CCTS | Iron & Steel; Cement; Pulp & Paper; Petrochemical; Textile; Aluminium; Refinery; Fertilizer; Chlor Alkali |

Table 1: Lists the activities, sectors and technologies identified by the Government of India under Article 6.2 and its official Offset and Compliance Mechanism of the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme.

The interaction of the Voluntary Carbon Market with Article 6 should also be strategically managed and leveraged since the VCM operates independently and does not directly impact NDC accounting.

As they say, any plan is as good as its implementation. Similarly, the effectiveness and impact of these newly established rules and standards will only become apparent if they sustain the test of time and maintain credibility. It is essential to recognise that this is a dynamic process, and the mechanism to course correct should be integral to its design. Ensuring transparency and environmental integrity should remain a priority and be consistently mainstreamed in policy design and negotiations if carbon markets are to endure and prove its mettle.

Mannat Jaspal is a Director and Fellow – Climate and Energy at the ORF Middle East