The modernisation of the global economy in the 21st century has been closely linked to the ubiquitous spread of digitalisation and datafication across both the public and private sectors. A corollary of this co-evolution of technology and governance mechanisms has been the evolution of knowledge economies arising from an increased collaboration between government, private sector, and academic ecosystems. A key component for strengthening a knowledge economy is the availability of knowledge or data generated and collated by the government for the use of different stakeholders. In the Gulf countries, as in most countries, this has resulted in the proliferation of Open Data Portals.

For the Gulf countries, the role of open and transparent data for strengthening the knowledge economy has become crucial. For instance, the region has seen high investment in Smart City initiatives, such as Saudi Arabia’s Neom and the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) Masdar City. It has also been actively encouraging the digital transformation of its governance infrastructure, which will require robust integration of technological platforms such as the Internet of Things (IoT), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and big data. Given that such projects and priorities require various domains of expertise and cannot be solved for by the public sector alone, Gulf countries may need to take a proactive approach to strengthen their knowledge economies by investing more in open data for stakeholders and experts across economic sectors.

Across the Gulf countries, barring Kuwait, which has no centralised portal, this has resulted in 14,729 datasets published. Most of this is led by Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which have surpassed other Gulf countries by thousands of datasets.

Datasets Published by Gulf Country, as of the 6th of May 2025

| Open Data Portal | Datasets Published |

| Saudi Open Data Platform | 10,916 |

| UAE’s Bayanat | 3,146 |

| Bahrain Open Data Portal | 448 |

| Qatar Open Data Portal | 159 |

| Oman Open Data Portal | 60 |

Sources: Saudi Arabia Open Data Portal, Bayanat, Bahrain Open Data Portal, Qatar Open Data Portal, Oman Data Portal

The Downsides of Open Data

While GCC countries have initiated Open Data Portals in recent years, the initiatives have faced bottlenecks. Research indicates that some inertial factors include: the lack of apparent benefits of maintaining open data platforms, pressure on government resources, inadequate operational coordination between government departments, lack of whole-of-government approach, legal ambiguity and risk of violating privacy standards by publishing sensitive data and technical issues such as lack of interoperable machine-readable formats for data publication.

An important factor here is the “lack of clear or apparent benefits of maintaining open data platforms”. For instance, the public may not necessarily appreciate the importance of maintaining such open data platforms; therefore, the benefit of open data platforms as a service may not be clear to governments, perhaps because it is not seen as a service outside the purview of researchers and analysts. Moreover, if anything, publishing raw open data without context and analysis may lead to confusion and misplaced scrutiny.

The Case for Open Data

There are benefits, nonetheless. Firstly, there is a global mandate for open data. The United Nations (UN) has identified building, monitoring and maintaining national data systems and evaluation programs as key components of its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The UN SDG preamble assigns to member states the responsibility for developing rigorous, high-quality, accessible, and reliable data sources and indicators at a national level.

Furthermore, dissemination of knowledge and data sharing practices by governments has become a useful indicator and predictor of long-term economic growth, particularly for developing countries. According to World Bank researchers, government data sharing and transparency practices can lead to increased scientific research and innovation, more accurate macroeconomic forecasts, and better effectiveness of monetary policies by making data available to “a broad brain trust”.

Still, open data practices cannot be implemented without decisions “at the highest level of policy” to mandate the release and maintenance of legally permissible data collected by governments and public institutions. Achieving this will require overcoming various administrative, legal and technical obstacles, as open data, by definition, needs to be free to use, reuse and share, accessible, machine-readable, timely, non-proprietary, maintained and should meet privacy and international standards.

A Path to Advancing e-Participation

One incentive for policymakers to engage with open data practices and maintain their open data portals to the highest standard is to improve their interaction with their citizens. Although Gulf countries may largely follow the tradition of having appointed rather than elected governments, the desire to encourage participation of citizens in governance and policymaking is still present. For instance, Gulf governments care about being competitive in e-Government in all its dimensions, as evidenced by their engagement with the UN e-Government Survey, and one way in which e-Government can be judged is by focusing on the use of online services to facilitate interaction between citizens and government.

This can be derived from the UN E-Participation Index (EPI). There are three levels to the index: e-Information, which is defined as “enabling participation by providing citizens with public information and access to information without or upon demand”; e-Consultation, which is defined as “engaging citizens in contributions to and deliberation on public policies and services”; and e-Decision-Making, which is defined as “empowering citizens through co-design of policy option and co-production of service components and delivery modalities”. Notably, e-Information leads to e-Consultation, as people cannot give proper input to governments without the government providing basic information. Moreover, both lead to e-Decision-Making, during which “citizens become the protagonists by leading the policymaking process”.

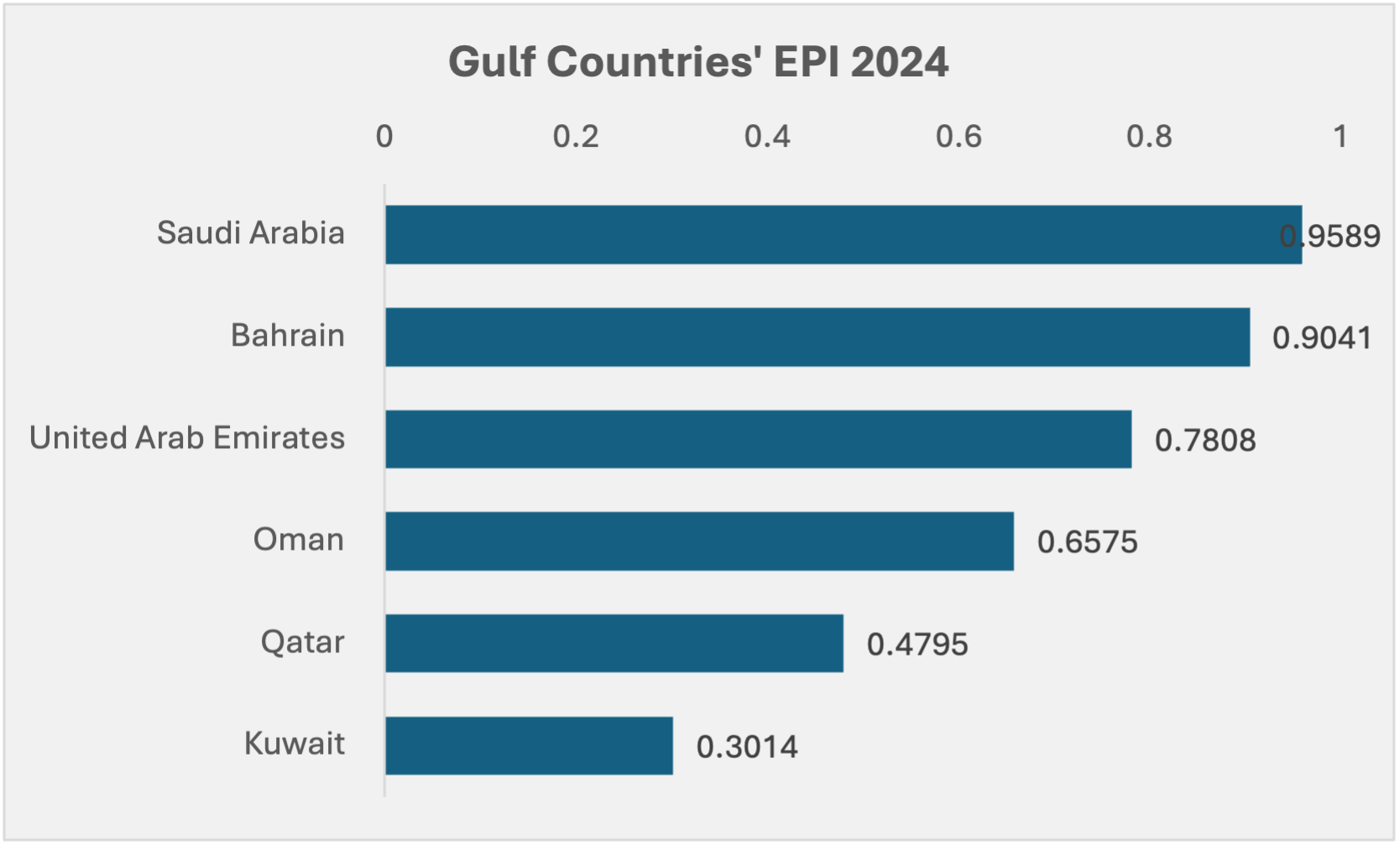

In 2024, Saudi Arabia emerged as the leading Gulf country in terms of the e-Participation Index, while Qatar and Kuwait remained below the world average of 0.4893. Saudi Arabia was ranked 7th in the world for its EPI score, moving 36 ranks higher than the 2022 report. Bahrain also made significant improvements by going up 71 ranks to be included in the top 20 globally. This indicates that Saudi Arabia and Bahrain have been taking e-participation very seriously over the past few years.

Gulf Countries EPI Ranking

| Country | Rank 2024 | Rank 2022 | Change |

| Saudi Arabia | 7 | 43 | +36 |

| Bahrain | 18 | 89 | +71 |

| United Arab Emirates | 37 | 18 | -19 |

| Oman | 61 | 50 | +11 |

| Qatar | 92 | 101 | +9 |

| Kuwait | 130 | 67 | -63 |

Source: UN E-Participation Index

One way to understand why Saudi Arabia is doing so well in e-Participation is to look at its survey responses to the E-Government Survey. In addition to having an open data portal, the Saudi government has dedicated e-Participation platforms such as “Tafaul”, “Istitlaa”, “Watani”, and the “Private Sector Feedback Platform”. This incentivises the government to ensure its open data portal is up to date, serving to maximise the utility of such platforms, while also acting as additional data points on the number and content of draft policies and legislation.

The development of aforementioned e-Participation platforms is part of a larger strategy by Saudi Arabia to cultivate a knowledge-based partnership between the public and private sectors to achieve the mandate of the Kingdom’s Vision 2030 of becoming one of the top ten most competitive economies of the world. By prioritising and normalising public-private consultations in legislative practices to create a “safe and stable investment environment,” the position of Saudi Arabia in the EPI rankings reflects a whole-of-government approach and administrative streamlining that can serve as a model for neighbouring jurisdictions.

Conclusion

Saudi Arabia and Bahrain’s leadership in the e-Participation Index demonstrates the value of investing in open data ecosystems—not only to promote innovation, economic growth, and sustainability, but also to enhance citizen engagement. Their progress offers a policy model for neighbouring Gulf states aiming to strengthen digital governance, enhance transparency, and build more inclusive knowledge economies. This is especially true for the Gulf countries, which may have ineffective open data efforts.

Siddharth Yadav is a Fellow with the Technology vertical at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) – Middle East.

Mahdi Ghuloom is a Junior Fellow, Geopolitics at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) – Middle East.