The strategic and investment relationship between the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Egypt has reached unprecedented levels of cooperation, epitomised by recent endeavours like the Ras El Hekma development project. This strategic alignment, however, presents a compelling paradox when juxtaposed with the underlying structure of their bilateral trade. In 2023, bilateral trade approached nearly US$7 billion, with UAE exports to Egypt valued at approximately US$4.5 billion and imports from Egypt at US$2.4 billion, figures that appear surprisingly modest given the combined economic weight of the two countries. While the partnership is a geopolitical and financial cornerstone, its trade dimension is yet to realise a commensurate depth and breadth.

A Trade Relationship of Peaks, Not Plateaus

The data suggests that the bilateral trade relationship is characterised by high-value, concentrated peaks in specific sectors rather than an integrated plateau across the full economic spectrum. For most product categories, the bilateral flow represents only a minor fraction of each nation’s total global trade, indicating a level of integration that appears surprisingly modest.

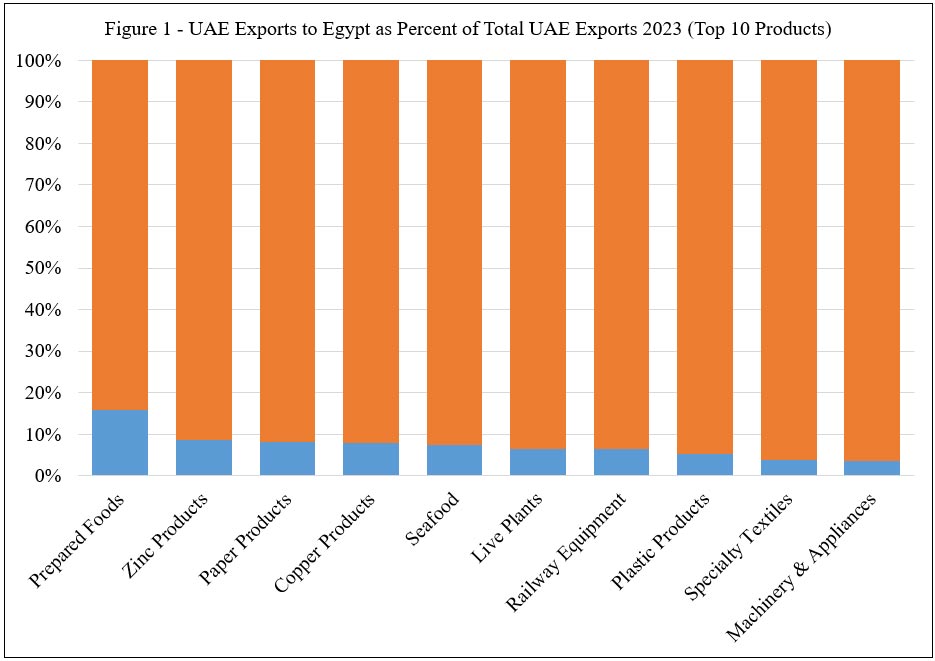

An examination of the UAE’s exports to Egypt underscores this point. Figure 1 illustrates that while certain products have a notable market share, most do not. For instance, exports of ‘Prepared Foods’ to Egypt represent a significant 15.7 percent of the UAE’s total global exports in that category. This clear peak demonstrates a strong trade channel. However, for other key goods that the UAE supplies to Egypt, the share is far more modest. For sectors such as ‘Plastic Products’ and ‘Machinery & Appliances’, Egypt as a destination accounts for only 5.3 percent and 3.5 percent of the UAE’s total exports in those categories, respectively.

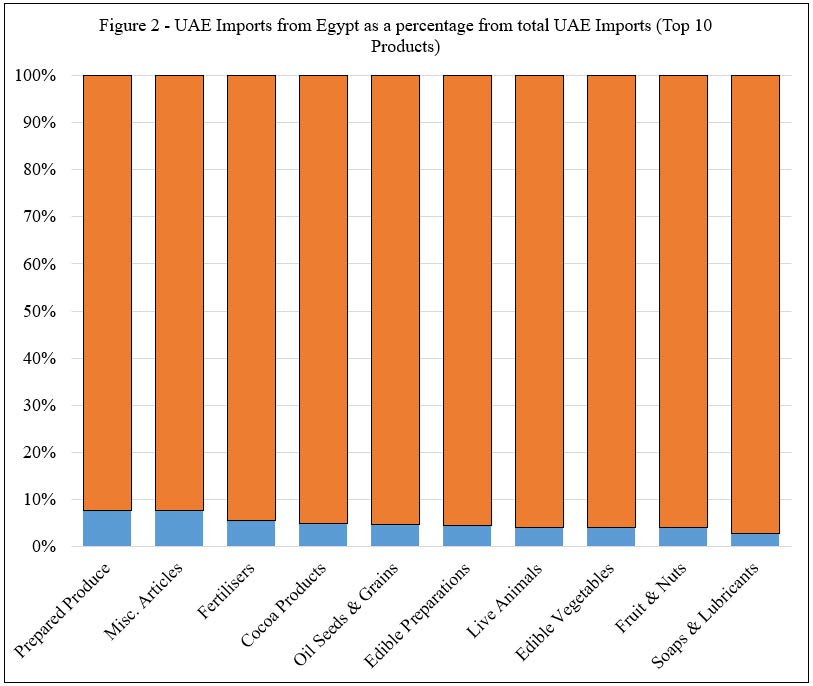

A similar pattern emerges when analysing UAE imports from Egypt. Figure 2 shows that Egypt’s role as a supplier to the hyper-competitive UAE market is also largely modest. There are notable exceptions where Egypt has carved out a respectable niche. For example, for ‘Prepared Produce’, Egypt supplies a solid 7.8 percent of the UAE’s total imports. Similarly, for ‘Misc. Articles’, Egypt’s share is 7.7 percent.

However, beyond these peaks, Egypt’s market share drops off significantly. In sectors such as ‘Essential Oils & Perfumery’, ‘Tobacco’, and ‘Salt, Sulphur & Stone’, Egypt’s share as a supplier to the UAE market dwindles to between 1.2 percent and 1.4 percent. Even in a core strength like ‘Fruit & Nuts’, the data shows Egypt supplies only 4.0 percent of the UAE’s total imports.

For a close neighbour and strategic partner, having such a low single-digit market share across so many product lines suggests that proximity and political goodwill have not helped overcome underlying competitiveness challenges. The trade relationship is shallow in its sectoral breadth. It is less a dense, interconnected web of commerce and more a series of distinct, high-volume channels, leaving vast swathes of the economic landscape relatively unconnected.

The Nature of Unrealised Potential

This observation of shallow integration corresponds directly with the significant, yet-to-be-realised trade potential that exists for both partners. Analysis indicates Egypt holds 1.5 billion in unrealised export potential to the UAE, while the UAE has an even larger 2.8 billion in untapped potential in the Egyptian market. However, the nature of this potential reveals a critical structural divergence between the two economies.

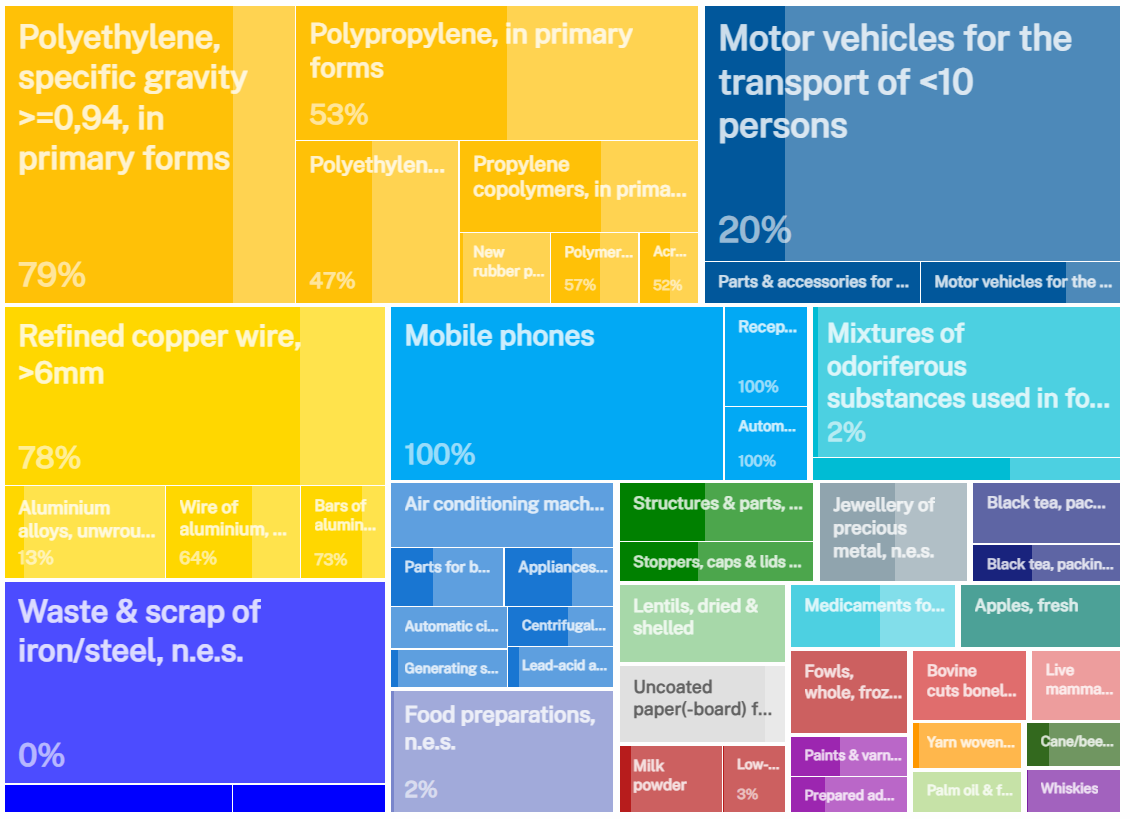

For the UAE, Graph 1 indicates that the greatest potential lies in expanding its role as a supplier of diverse, value-added industrial goods, yet even here, the relationship is operating well below its ceiling. The data reveals significant untapped potential across its core industrial strengths. The opportunity is most pronounced in sectors like ‘Motor Vehicles & Parts’, with a vast 80 percent of potential unrealised, respectively.

Graph 1: UAE’s Export Potential to Egypt by Product Category

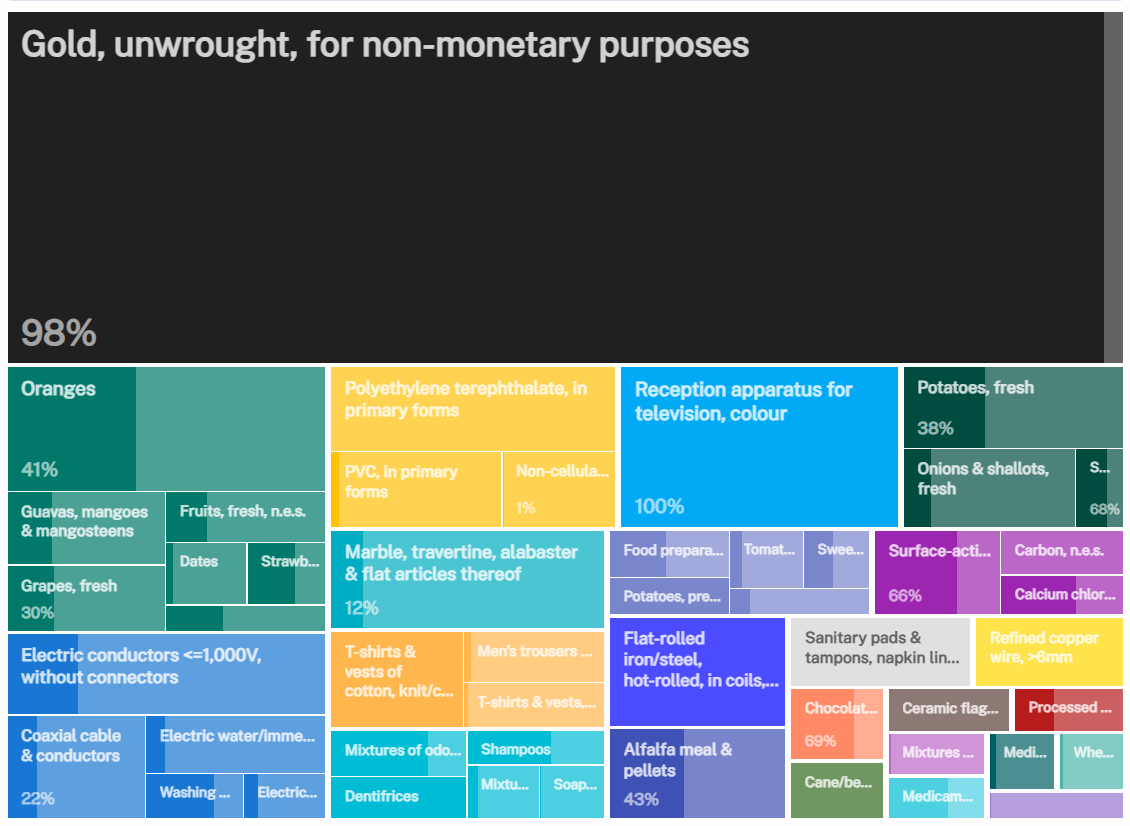

For Egypt, the export profile is marked by a profound and precarious concentration that highlights a critical failure to capitalise on the UAE market. Graph 2 details the specific products driving this potential. The relationship is overwhelmingly defined by a single product: ‘Gold, unwrought, for non-monetary purposes’, where a staggering 98 percent of the export potential is already realised. This success, however, masks varied performance across other products. For example, in fresh produce, Egypt has realised 41 percent of its potential for ‘Oranges’ and 38% for ‘Potatoes, fresh’, leaving significant room for growth. In contrast, some sectors show high realisation, such as ‘Reception apparatus for television, colour’ at 100 percent, while others, like ‘Marble, travertine, alabaster & flat articles thereof’ are only at 12 percent of their realised potential.

Graph 2: Egypt’s Export Potential to the United Arab Emirates by Product Category

This divergence is most vivid when comparing the same sectors. While the UAE has significant room to grow its industrial exports to Egypt, Egypt has barely begun to compete in these same areas. This reveals more than a simple trade imbalance; it exposes a structural imbalance in industrial competitiveness and a shared story of vast, unrealised economic potential.

The reason bilateral trade constitutes such a small percentage of each country’s global total is precisely because this immense potential remains untapped. The relationship is not deeply integrated across many sectors because Egypt has not yet developed the competitive industrial capacity to export a diversified basket of goods to the UAE, while the UAE, despite its success, still has significant room to deepen its market penetration in Egypt. The data suggests that while Egypt has successfully leveraged its geographic position for commodity trade, it has struggled to turn that proximity into a competitive advantage for its manufacturing base, even in one of its most important and friendly markets.

Given the proximity, shared membership in trade frameworks like the Greater Arab Free Trade Area (GAFTA) and the deep political and investment bonds, the observed level of shallow integration may necessitate a deeper reconsideration of bilateral trade.

Strategic Imperatives for Deepening UAE–Egypt Trade

The current structure of UAE–Egypt trade reveals not just underperformance but a more fundamental challenge: the disjuncture between strategic alignment and economic depth. While the Ras El Hekma deal and other high-profile investments signal unprecedented trust and long-term partnership, the narrow, peak-heavy trade flows tell a story of sectoral silos rather than systemic integration. Moving from alignment to activation requires recalibrating how both states approach bilateral commerce.

At the heart of Egypt’s underperformance lies a structural competitiveness gap. Despite preferential access and geographic proximity, Egyptian exporters have failed to meaningfully penetrate the UAE’s high-demand, low-tariff marketplace across most industrial categories. This is not merely a function of market access; it reflects weaknesses in scale, quality and certification infrastructure. Egypt must establish targeted export acceleration zones linked specifically to Gulf-facing trade, particularly in sectors with large unrealised potential like plastics, rubber, metals, and food. These zones should provide bundled services: export credit, quality assurance and fast-track regulatory clearances aimed at meeting UAE standards. The Egyptian Export Development Authority, in coordination with Emirati logistics players like DP World, could establish a bilateral certification corridor, where Egyptian goods are pre-cleared in bonded zones for seamless entry into Emirati markets.

However, there is also a need to rewire the trade architecture beyond the megadeal. The Ras El Hekma development is often cited as a flagship of UAE–Egypt economic cooperation, but megadeals of this kind tend to be capital-intensive, elite-led and slow-moving. The trade relationship, by contrast, is quick, decentralised and driven by SMEs. Current data reveals that these ecosystems barely interact. The real unrealised potential may not lie in macro-projects, but in mid-cap industrial exchange. As a result, more integration is required for the tier two trade corridor focused on building SME consortia in both countries within complementary sectors like Egyptian agri-processing for UAE food security strategies. These should be embedded in existing industrial parks with bilateral digital trade platforms to match buyers and suppliers, with efforts to include dedicated funding from sovereign entities like ADQ and Egypt Ventures.

Further, the data shows asymmetry not just in volume but in the maturity of sectoral engagement. The UAE’s unrealised export potential lies in high-value industrial goods, suggesting that its exporters have established partial footholds. Egypt, meanwhile, is still in the foothill stages, especially in goods like plastics and ferrous metals. It would be important to define sector-specific penetration benchmarks, beyond just aggregate trade targets. Egypt and the UAE could establish bilateral sector integration committees in 3–4 priority verticals. For example, growing Egyptian share of UAE plastic imports from 3 percent to 7 percent over three years or increasing Emirati machine exports by 50 percent in targeted product codes. These targets can be backed by financial instruments, de-risked procurement frameworks and forward purchase agreements.

Upgrading trade architecture would also be critical to support this increased trade. With the UAE investing heavily in ports like Ain Sokhna and the Red Sea corridor, the two sides have a rare opportunity to turn logistics infrastructure into actual trade volume. It will be important to develop priority shipping lanes for high-potential sectors with guaranteed frequency, faster customs processing and digitally enabled documentation. Pairing this with preferential warehouse access in Jebel Ali and Khalifa Port for Egyptian suppliers who meet performance benchmarks could create a fast lane within the broader GCC trade space.

The UAE is a global logistics powerhouse, and Egypt is a manufacturing hub in search of scale. The trade potential and strategic trust are significant. Now, it must be translated into commercial depth. The next phase of UAE–Egypt economic cooperation must focus on building a shared industrial spine.

Samriddhi Vij is an Associate Fellow, Geopolitics at ORF Middle East.

Ahmed Dawoud is an Economist and the Head of the Data Analytics Unit at the Egyptian Center for Economic Studies (ECES).

Ahmed Wael Ahmed Habashy is an AI Engineer at the Egyptian Center for Economic Studies (ECES), specialising in the development of intelligent systems for labour market and economic analysis.