The questions shaping growth across Eurasia and Africa have moved beyond goods production to their cross-border movement and how efficiently people, capital and data can connect. By linking its sea, air, rail, deep-water ports and digital infrastructure, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has built a strong logistics and connectivity system. This integration has given the UAE an edge since it uses its geography not just for faster trade routes, but as a form of economic resilience where goods and people keep moving even during any disruptions.

Why Rethinking Connectivity Matters for the UAE and the GCC

For the UAE and its Gulf neighbours, connectivity is an economic policy tool for driving growth and competitiveness. The country’s multimodal strategy lowers the “time cost of distance” between Asia, Africa, and Europe through integrated seaports, airports, highways, and fast, predictable border procedures. Recent milestones underscore this shift from blueprint to operations. The Etihad Rail Project envisions transforming the mobility of passengers and freight across the country by linking 11 cities, serving major ports such as Jebel Ali, Khalifa, and Ruwais, with planned freight capacity set to reach about 60 million tonnes annually by 2030. Additionally, the introduction of the new low-fare CX01 Dubai–Abu Dhabi express bus and door-to-door journey planning via Etihad Rail’s integration with Citymapper makes passenger commute convenient and encourages shared, lower-emission travel options. Dubai is forecast to rank among the world’s top three destinations in Q4 2025, validating continued investment in air capacity, surface connectivity, and event infrastructure, and strengthening the case for multimodal redundancy when sea or air corridors face shocks.

Dubai is forecast to rank among the world’s top three destinations in Q4 2025, validating continued investment in air capacity, surface connectivity, and event infrastructure, and strengthening the case for multimodal redundancy when sea or air corridors face shocks.

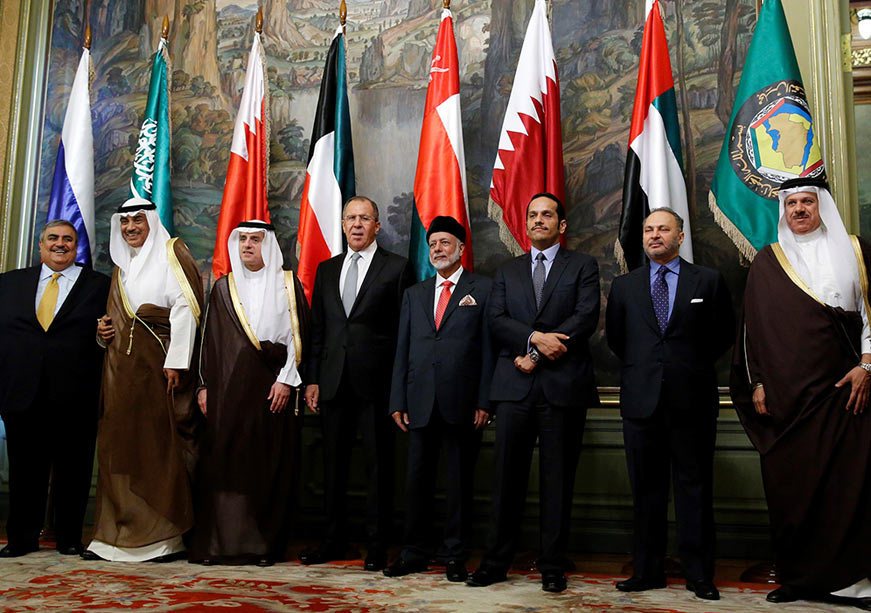

Ports, Corridors, and Economic Diplomacy

The UAE’s seaports anchor the country’s role on the Maritime Silk Road. Jebel Ali, the world’s largest man-made port, together with Khalifa Port and Khor Fakkan, has been expanded and digitised to serve as preferred entry points for goods bound for the wider MENA market, while facilitating China–Europe–Africa flows. Domestic ports are the launchpads for extending outward corridor strategies as well. For instance, UAE-linked port and logistics investments in East Africa (including terminals such as Berbera and Dakar) use the Emirates’ hubs as staging grounds for two-way trade. This hard infrastructure is matched by economic diplomacy. A growing network of Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements (CEPAs) across Asia, Africa, and Europe reduces tariffs, streamlines customs, and promotes joint ventures. Engagement in plurilateral forums such as G20 and BRICS gives the UAE a platform to advocate for resilient supply chains and sustainable infrastructure finance. Sovereign wealth funds reinforce the strategy by co-investing in global logistics, energy, and data assets, helping shape “new geographies” that the UAE can plug into with speed.

China Linkages Without Dependency

The UAE’s corridor architecture is compatible with China’s Belt and Road whereChinese manufacturers and e-commerce platforms can consolidate, customise, and re-export through free zones, using rail–port–air integration and single-window digital documentation to reach Europe and Africa on predictable schedules. On the ground, large China-linked wholesale districts in Dubai shorten replenishment cycles, while a growing community of Chinese entrepreneurs, engineers, and service professionals increases demand for flights, housing, education, and hospitality. Policy instruments such as Dubai’s Free Zone Mainland Operating Permit tighten the loop between innovation clusters and citywide customers, shortening time-to-market for tech firms, consultancies, and traders.

Unlike many Belt and Road (BRI) ventures that rely on state-backed loans and create long-term financial dependencies, the UAE’s approach emphasises commercial viability, risk-sharing, and diversification. Instead of debt-funded megaprojects, the UAE builds partnerships through equity-based joint ventures and public–private collaborations. For instance, DP World’s 30-year concession at Berbera in Somaliland and the US$1.1 billion Port of Ndayane in Senegal are structured as joint ventures with host governments, involving commercial concessions rather than sovereign loans. These projects illustrate how the UAE extends connectivity without burdening partner countries with debt or political conditions.

Instead of debt-funded megaprojects, the UAE builds partnerships through equity-based joint ventures and public–private collaborations.

Within the UAE, Chinese–Emirati cooperation similarly operates through open-market mechanisms rather than state-driven procurement. The Yiwu Market Dubai, a partnership between DP World and China Commodity City Group, has created a wholesale hub within Jebel Ali Free Zone (JAFZA) that accelerates re-export trade across Africa and the Middle East. Complementary measures such as the Free Zone Mainland Operating Permit allow Chinese and other foreign firms to operate directly onshore under clear regulatory oversight, avoiding exclusive or protectionist arrangements. This approach contrasts sharply with the BRI’s debt-heavy infrastructure model in parts of Africa and Central Asia, where reliance on Chinese policy banks has often led to restructurings and dependency. The UAE, by contrast, hedges concentration risk through a diversified network of partners. Its Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements (CEPAs), notably with India, ensure multiple connectivity routes coexist with, rather than depend on, Chinese financing or control.

By maintaining high transparency, co-financing, and adherence to international standards, the UAE transforms connectivity into cooperation, without ceding autonomy or strategic leverage.

People as the Payload: A Combined View of Migration

Talent mobility is part of the UAE’s connectivity model. High-skilled professionals power healthcare, finance, higher education, and the digital economy. Semi-skilled and low-skilled workers build and operate the railways, ports, airports, logistics parks, hotels, and energy sites. Longer-term residency pathways and streamlined onboarding reduce hiring friction and accelerate project delivery. Even recent demographic shifts matter as the steady inflow of African professionals and entrepreneurs is diversifying supplier bases and strengthening commercial links with African cities. At the same time, an uptick of educated, entrepreneurial Russian residents across IT, design, cybersecurity, proptech, and e-commerce has broadened the small and medium enterprises (SMEs) base, deepened local talent pools, and increased utilisation of the UAE’s payments, cloud/data, and logistics infrastructure. For carriers and airports, these communities translate into steadier year-round load factors and stronger route economics. For cities, they underpin demand for schools, housing, and neighbourhood amenities.

Carving Productive Economic Bases

The UAE has consistently converted land and shoreline into productive economic space. High-rise business districts, integrated waterfronts, artificial islands, and master-planned innovation zones operate as market-making platforms rather than isolated real estate projects. Mixed-use districts near ports and airports, stitched together by metro, tram, and highways, shorten the distance between customers and suppliers and enable same-day services. Leisure and convention precincts sustain airline routes and hotel capacity, while driving demand for perishables handling and express freight. Industrial cities and energy parks in formerly undeveloped areas work because power, water, roads, fibre, and emergency services are delivered ahead of tenants. Between Abu Dhabi and Dubai, a newly approved multi-billion-dirham “mini-city” between Zayed International and Al Maktoum International exemplifies this approach. Abu Dhabi’s Livability Strategy pushes the same logic into the neighbourhood scale. When stations are fed by safe first- and last-mile options, national logistics efficiency improves.

Between Abu Dhabi and Dubai, a newly approved multi-billion-dirham “mini-city” between Zayed International and Al Maktoum International exemplifies this approach.

Air Hubs and the Digital Twins of Trade

Aviation remains the UAE’s main link between global markets, connecting both East–West and emerging South–South corridors. Flagship carriers like Emirates and Etihad serve as “super-connectors,” while the AED 128-billion expansion of Al Maktoum International aims to create the world’s largest airport by capacity, consolidating the country’s position as a global aviation hub. The Dubai Airshow 2025 will spotlight this momentum by convening manufacturers, airlines, and technology providers to focus on the efficiency, sustainability, and resilience of air networks. Crucially, the UAE is also building a digital twin of its transport system, integrating air, land, and sea logistics through smart platforms for travel planning, customs, and cargo management. Near-universal 5G coverage and one of the world’s highest internet penetration rates ensure the country can run real-time operations using IoT, secure digital documentation, and coordinated transport planning. In short, “blue fiber” is now as critical to the UAE’s connectivity as blue water and runways.

Strategic Corridors and Market Access

The UAE’s corridor strategy is multi-directional, aimed at co-investing in infrastructure and aligning regulatory frameworks. Africa Gateway initiatives, supported by UAE-linked port and logistics investments, give East and West African exporters reliable staging grounds and faster access to markets. Central Asian and Silk Road linkages position the Emirates as a southern terminus for land-sea routes that connect China and Central Asia to Europe. India and South Asia are being integrated more tightly through the UAE–India CEPA and associated logistics corridors, enabling re-exports and just-in-time supply chains across the subcontinent.

Africa Gateway initiatives, supported by UAE-linked port and logistics investments, give East and West African exporters reliable staging grounds and faster access to markets. Central Asian and Silk Road linkages position the Emirates as a southern terminus for land-sea routes that connect China and Central Asia to Europe.

The UAE as a Nexus State

The UAE is often described as a nexus state. A small country that multiplies its influence by connecting regions (Asia, Africa, Europe), modes (sea, air, rail, digital), and sectors (energy, finance, logistics, technology, culture). The COVID-19 pandemic made this role visible, and that experience now informs peacetime corridor design, insurance structures, and preparedness playbooks. It is also a template for partners across Africa, Asia, and Europe to practice by co-financing infrastructure and co-creating standards that keep corridors open when they are needed most.

Kristian Alexander is a Senior Fellow and Lead Researcher at the Rabdan Institute for Security & Defence Research, Abu Dhabi, UAE.