Arab states are splitting: some moving beyond oil, others stuck in dependence—shaping two futures.

For decades, the political economy of the Arab World has been viewed as a group of “petro-states”; countries whose economies were built on oil. It is often suggested that the region’s oil would converge on a singular trajectory of gradual diversification. A forensic analysis of World Bank oil rent data from 2001 to 2021, however, complicates this assumption. By isolating the economies with active hydrocarbon exposure and adjusting for data constraints in conflict zones, a dramatic bifurcation emerges. The Arab World is splitting into two distinct economic categories: the “Post-Rentier Aspirants,” who are leveraging capital to mitigate their structural dependency, and the “Hyper-Rentiers,” whose economies have become more rigid, volatile and exposed to the global energy markets. It can be argued that the “Arab Oil Economy” as a unified construct is obsolete, and instead a widening “Rentier Divergence” is taking shape, one that will redefine the region’s stability in the coming decade.

Defining the Universe of Analysis

To construct a framework for this comparative analysis, the World Bank’s “Oil Rents (% of GDP)” dataset was used, benchmarking national performance against the aggregate “Arab World” average. The Arab World is defined, as per World Bank classification, to include Algeria, Bahrain, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), West Bank and Gaza, Yemen and Somalia. However, the raw data required three specific filters to ensure the integrity of the comparison. First, economies with effectively zero hydrocarbon rents (Comoros, Djibouti, Jordan, Lebanon, Mauritania, West Bank and Gaza, Morocco and Somalia) in both 2001 and 2021 were excluded because including these states would distort the analysis, as their economic challenges are structurally distinct from the “resource curse” dynamics affecting the producers. Second, 2021 data was unavailable for Kuwait and Syria, and as a result, 2020 data were used as a proxy. This adjustment ensured that these critical actors remained visible in the rankings. Third, Yemen was excluded from the final dataset, as its most recent reliable economic data dates to 2018. In a region characterised by rapid shifts, pre-2020 data would fail to capture the structural ruptures caused by the COVID-19 demand shock and subsequent geopolitical realignments.

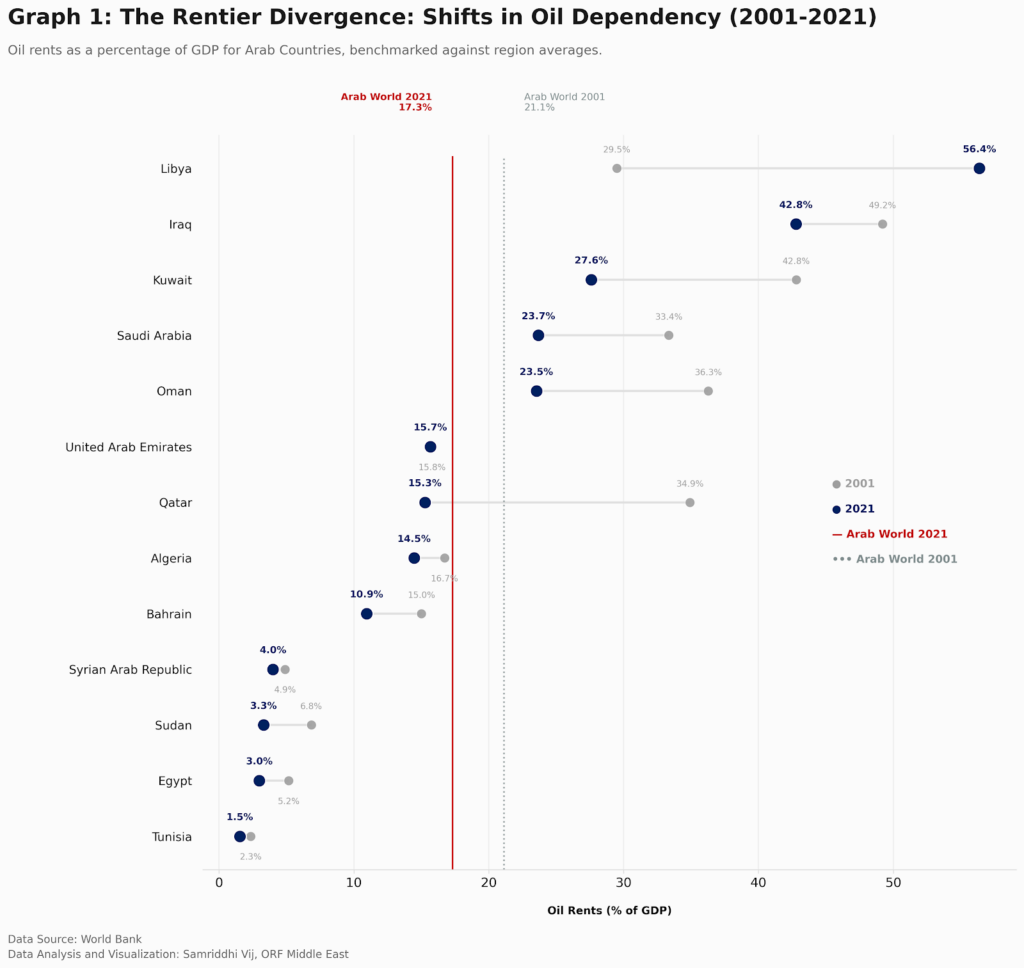

The result of the final analysis is reported in Graph 1[1], which illustrates the shift in Oil Rents (percentage of GDP) for 13 hydrocarbon states of the Arab World between 2001 to 2021 against the average of the region.

Hierarchy of Oil Dependence and Trajectory of Change

The 2021 snapshot reveals a stark hierarchy of exposure. When ranked from most to least dependent, the region organises itself into three distinct tiers of vulnerability.

The first classification is the “Hyper-Rentiers”, which exhibit greater than 30 percent of GDP dependence on oil. At the apex of this dependency lies Libya, with oil rents constituting a staggering 56.4 percent of GDP. It is followed by Iraq at 42.8 percent. These figures represent more than just economic data; they are indicators of systemic fragility. In both cases, the hydrocarbon sector is not merely a dominant industry but functions as the primary economic organ, displacing all other economic activity.

The next tier is the “Structural Rentiers”, for which 20– 30 percent of the GDP represents oil rents. Gulf powerhouses like Kuwait (27.6 percent) and Saudi Arabia (23.7 percent), alongside Oman (23.5 percent) reside here. For these states, the government’s capacity to pay wages, subsidise energy and maintain the social contract remains directly tied to oil revenues.

The Arab World is splitting into two distinct economic species: the “Post-Rentier Aspirants,” who are leveraging capital to suppress their structural dependency, and the “Hyper-Rentiers,” whose economies have become more rigid, volatile, and exposed to the global energy markets.

The final tier is of the “Diversified & Transitional” economies with less than 20 percent of the GDP derived from oil rents. The UAE sits at 15.7 percent, effectively tying with Qatar (15.3 percent). Algeria (14.5 percent) and Bahrain (10.9 percent) follow. Egypt (3.0 percent) and Tunisia (1.5 percent) round out the list, representing economies where oil functions as a fiscal rather than a structural foundation.

The static rankings of 2021 tell only half the story. The true analytical insight lies in the delta, the change over time. By comparing the 2001 baseline with the 2021 reality, the region’s economies can be mapped not only by their current position but also by the velocity and direction of their trajectory. This longitudinal view reveals a region that is fragmenting into four distinct pathways: the Aggressive Diversifiers, the Passive Diversifiers, the Stagnant Middle, and the Collapsed Outliers.

The most dramatic statistical shifts from 2001 to 2021 have occurred among the Aggressive Diversifiers, led by Qatar, which reduced its oil rent share by nearly 20 percentage points (dropping from roughly 35 percent to 15.3 percent). However, this needs to be understood in context to Qatar’s considerable gas reserves, as the hydrocarbon activities contributed 35 percent to its GDP in 2024. Qatar is followed closely by Kuwait and Oman, which posted declines of 15.2 and 12.7 percentage points, respectively. Yet the drivers here are divergent. Qatar’s shift reflects the massive expansion of its gas (LNG) economy, effectively diluting the oil share. Kuwait’s decline is more a function of price volatility than structural reform. Oman, facing the reality of dwindling reserves, falls into this category out of geological necessity rather than a strategic choice.

A second tier, the Passive Diversifiers, includes heavyweights such as Saudi Arabia and Iraq, alongside smaller players like Bahrain. Saudi Arabia saw a moderate drop of 9.7 percentage points, while Iraq reduced its dependency by 6.4 points and Bahrain by 4.1 points. In these cases, the reduction in oil rents has not been sharp enough to fundamentally alter the political economy. For Saudi Arabia, the 9.7 point drop reflects the early stages of Vision 2030. Iraq’s reduction is particularly concerning; despite a 6.4-point drop, it remains structurally hyper-dependent (at 42.8 percent).

By comparing the 2001 baseline with the 2021 reality, it reveals a region that is fragmenting into four distinct pathways: the Aggressive Diversifiers, the Passive Diversifiers, the Stagnant Middle, and the Collapsed Outliers.

The third trajectory is defined by the Stagnant Middle, a group of countries where the hydrocarbon needle has barely moved in twenty years. The UAE is the counter-intuitive anchor of this group, structurally flat with a negligible change of just 0.1 percentage points (15.8 percent to 15.7percent). This stability suggests a “diversification ceiling”, where service-sector gains begin to plateau. This group also includes Algeria (-2.2 points), Egypt (-2.2 points), Syria (-0.9 points), and Tunisia (-0.8 points). These nations are neither expanding their oil sectors nor successfully diversifying away from them, remaining trapped in a suspended state of low-growth reliance.

Finally, the region is bookended by the Collapsed State, represented by Libya, which moved sharply in the opposite direction. Increasing its oil dependency by nearly 27 percentage points, Libya stands as a graphical outlier that distorts the entire regional trend. This surge to 56.4 percent dependency is not a sign of oil wealth but of institutional disintegration, where conflict has obliterated the non-oil economy, leaving hydrocarbon exports as the sole, surviving pillar of the state apparatus.

The most revealing metric in this graph is the Arab World aggregate dependency itself, which has declined from 21.1 percent in 2001 to 17.3 percent in 2021. The average is no longer a measure of central tendency but a mathematical proof of two separating worlds. To the right of the 17.3 percent line, the Hyper-Rentiers (Libya, Iraq, Kuwait) have effectively decoupled from the region’s diversification trajectory, creating a reality where the state remains consumed by the volatility of the barrel. Conversely, to the left are countries that have established a new structural baseline below the regional average. Thus, the Middle East is not converging toward a modernised middle; instead, it represents an increasingly bifurcating reality.

Samriddhi Vij is an Associate Fellow, Geopolitics, at ORF Middle East.

[1]After the data was sourced from the World Bank, it was cleaned, analysed and visualised by the author. The graph was designed using Google Gemini, which is Google’s AI tool, acting as an intelligent assistant that understands and processes text, images, audio, video and code.