Iranians are protesting because the social contract, economic stability in exchange for obedience has collapsed, while isolation has become more profitable for elites than reform

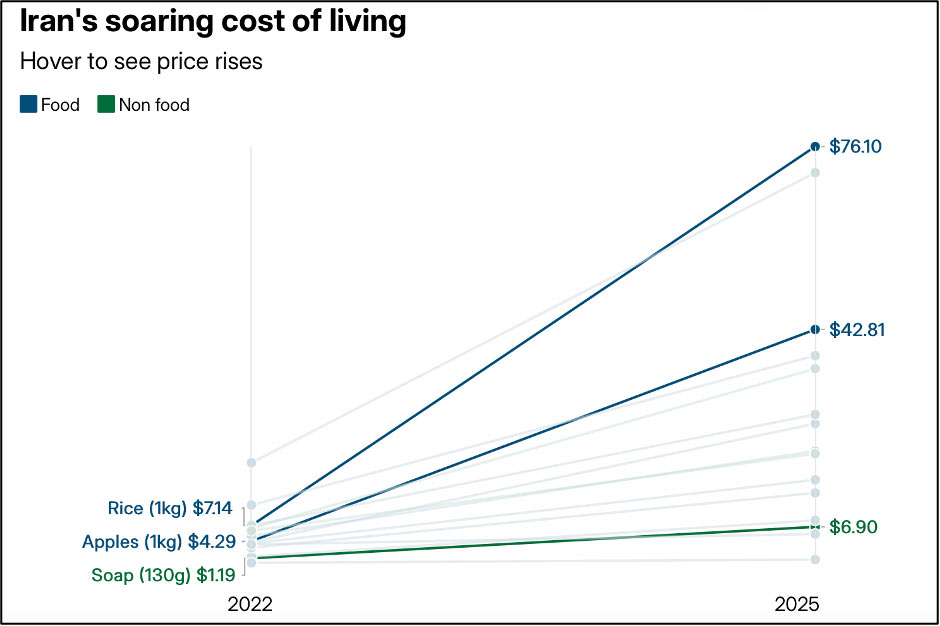

The protests sweeping major Iranian cities this month were sparked by drastic currency devaluation, with the rial breaching 1.45 million to the US dollar and food price inflation exceeding 70 percent. While the immediate trigger is Iran’s soaring cost of living, the underlying causes are structural frameworks that have made international isolation more profitable for the Iranian elite than peaceful integration into the world order (refer to the graph).

Source: The National

Iran’s current economic collapse results from its “resistance economy” evolving from an ideological posture into a predatory shadow economy. For the past decade, external sanctions and internal mismanagement have created a black economy in Iran, which is built on the illicit sale of oil through a “ghost fleet” of tankers. However, the mechanisms designed to ensure regime survival now incentivise actively cannibalising the nation’s economy.

From Resistance to Rent-Seeking

The standard narrative suggests that the United States-led “maximum pressure” and other sanctions starved the Iranian economy of foreign currency, forcing the regime to resort to illicit activities to fund its strategic priorities. While true, this view misses the systemic shift that occurred over the last few years. The negative reinforcement loop—where nuclear escalation triggers sanctions, necessitating ghost oil sales to countries like China through elaborate mechanisms, and the generated revenuefurther financing nuclear advancement—has fundamentally restructured the Iranian state. It has shifted the norms of the economy from a transparent public sector to opaque, securitised networks.

In Iran, the revenue from the ghost oil sales is effectively ring-fenced for the “shadow budget” that finances missile programs, regional proxies and the enrichment apparatus.

When Iran sells 1.5 million barrels of oil per day via its “ghost fleet”, that revenue does not enter the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) through standard SWIFT mechanisms. It enters a shadow banking system managed by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and affiliated middlemen in hubs around Asia. Crucially, this process incurs a massive “sanctions discount”. This shadow economy has empowered a powerful military elite within the regime, who profit immensely from the friction created by sanctions. For these actors, opaque, heavily discounted trade is more lucrative than transparent, taxed commerce. The nuclear programme, therefore, aims to act as a strategic deterrent against the West and is considered a necessary pretext to maintain the state of emergency that justifies this opaque economic structure.

The current uprising is, in part, determined by this shadowing of state revenue and the resultant economic fractures. A functional state uses commodity export revenue to defend its currency and subsidise public goods. However, in Iran, the revenue from the ghost oil sales is effectively ring-fenced to finance missile programmes, regional proxies, and the enrichment apparatus.

This leaves the public budget—the one responsible for wages, pensions, and subsidies— severely constrained. The government cannot borrow internationally due to financial isolation, and it cannot access its own oil wealth, which is trapped in the shadow loop. The regime’s response, culminating in President Pezeshkian’s 2026 draft budget, appears classical fiscal mismanagement- printing money to cover the deficit while proposing wage hikes. The decision to abandon the preferential exchange rate of 28,500 Iranian tomans for essential imports was the breaking point.

The resulting 70 percent food price inflation was not an accident of policy, it was a symptom of a system prioritizing security over the public good.

This move was almost an admission by the state that it would no longer subsidise the basic necessities of its citizens in favour of preserving hard currency for the security apparatus. The resulting food price inflation was not an accident of policy; it was the consequence of a system prioritising security over public good. The Iranian people are on the streets because the social contract—acceptance of authoritarian rule in exchange for a degree of economic stability—has been unilaterally dissolved by the state.

Breaking the Cycle

Why does the system persist if it is leading to national ruin? The answer lies in the economic concept of path dependence, where the current and future situations are governed by past decisions, events and processes, even if they are no longer the most rational choices. The negative reinforcement loop has become self-sustaining because the incentives of the ruling elite have been completely decoupled from the interests of the general population. In most economies, elite wealth is generally tied to overall GDP growth. In Iran’s resistance-based economy, elite wealth is tied to the continuation of isolation.

If Iran were to normalize relations and re-enter the global economy tomorrow, this elite wealth would vanish.

Therefore, any attempt by civilian technocrats within the government to de-escalate nuclear tensions is actively sabotaged. The loop is resilient not because of ideological fervour, but because of a cold, hard rent-seeking approach. The system cannot reform because the very act of reform would bankrupt its most powerful stakeholders.

Given this entrenched structure, standard diplomatic solutions or piecemeal sanctions relief are destined to fail. They will merely feed new liquidity into the existing predatory loop without altering its mechanics. Breaking the cycle requires a simultaneous, exogenous, and endogenous shock severe enough to shatter the current equilibrium.

Internationally, this would require enforcement mechanisms to move beyond targeting the Iranian state and focus pointedly on the connecting nodes of the third-party networks in Asia that facilitate the ghost oil trade. Only by making the shadow oil sales prohibitively expensive, raising the cost of laundering beyond the profit margins, can the financial incentives of the elite be curtailed. Domestically, the loop only breaks when the cost of suppressing the population exceeds the revenue generated by the shadow economy. That threshold appears to be nearing. The current economic spiral indicates the regime is running out of road. However, history suggests that such systems rarely dismantle themselves peacefully; they usually persist until state insolvency leads to a fracturing of the security apparatus itself.

Internationally, this would require international enforcement mechanisms to move beyond targeting the Iranian state and focus pointedly on the connecting nodes of the third-party networks in Asia that facilitate the ghost oil trade.

Until the economic incentives for opacity are removed, the loop will continue, converting Iran’s natural resource wealth into enriched uranium and social chaos.

Samriddhi Vij is an Associate Fellow, Geopolitics, at ORF Middle East.