More than two years ago, Tunisian President Kais Saied publicly rejected a much-needed International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan at a time when the country’s economy was facing a severe, multifaceted crisis rooted in long-standing structural imbalances. It stemmed from a fiscal model that had become unsustainable over the past decade. As of 2025, the country’s public debt passed the 80 percent -of-GDP mark, creating a precarious situation with high gross financing needs and rollover pressure.

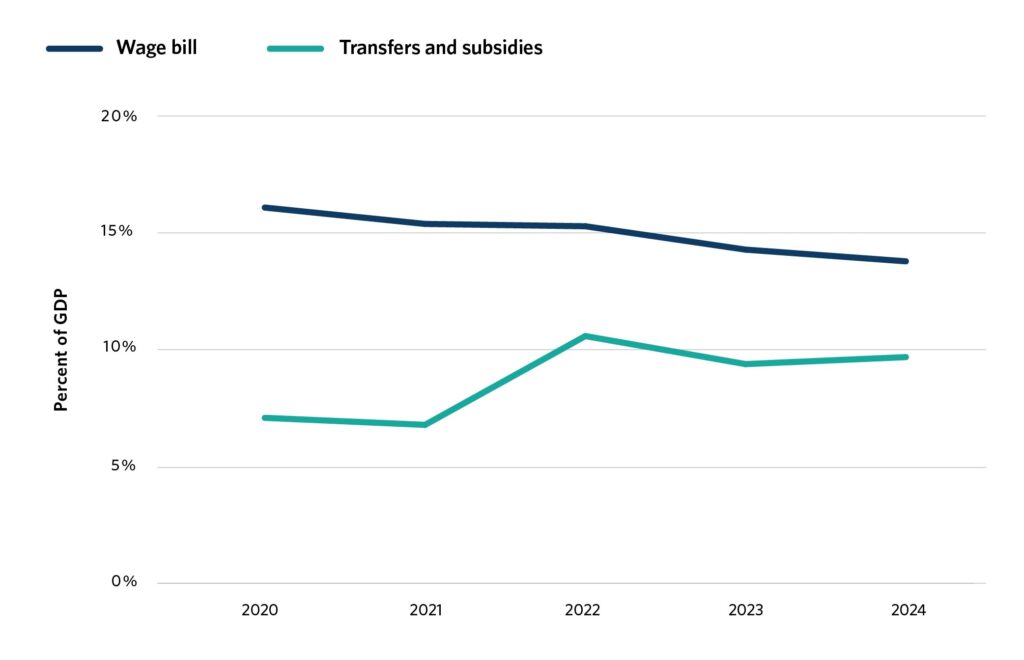

This debt burden has been driven by several factors. Public–sector wage bills in Tunisia accounted for 16 percent of the GDP in 2020, among the highest globally. A subsidy system for essentials such as food and energy remains costly and inefficient. Energy subsidies alone doubled to 5.3 percent of GDP in 2022.. A large portfolio of state-owned enterprises (SOE) continues to strain public finances as their collective debt totalled nearly 40 percent of Tunisia’s GDP, according to Fitch estimates. The Fitch credit rating agency downgraded Tunisia’s sovereign debt to CCC- (default) in 2023. The consequence of this poor fiscal planning translates into economic hardships in daily life. Foreign exchange constraints have contributed to recurring shortages of imported goods such as sugar, flour and rice, while inflation remains elevated at 5.6 percent.

In response to the escalating crisis, Tunisia reached a staff-level agreement with the IMF in October 2022 for a US$1.9 billion under the Extended Fund Facility. Beyond the loan, this programme was meant to act as a catalyst: securing IMF endorsement was essential to unlocking larger budgetary support from international partners. Chief among these was the European Union’s (EU) proposed US$1 billion loan, which was contingent on Tunisia securing the IMF deal. The programme was designed to address structural weaknesses through standard fiscal and structural reforms.

However, Saied publicly rejected key IMF terms, characterising them as “diktats” that could threaten public peace and as unacceptable infringements on national sovereignty. Domestically, the powerful Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT) also resisted the IMF package, especially opposing subsidy removal and wage freezes that made the reforms politically untenable.

Following the IMF programme’s suspension, the Tunisian government has pursued an alternative economic strategy focused on Saied’s belief that the “Tunisians must count on themselves”. It is important to analyse government measures, assess which initiatives have proven useful, identify the challenges that persist and ultimately answer the central question: can Tunisia recover without the IMF?

Tunisia’s Progress Report of Recovery

Tunisia has pursued a mix of domestic measures and external financing to achieve economic self-determination. The country’s Parliament authorised the Central Bank of Tunisia (BCT) to finance the budget by up to TND 7 billion at zero interest, allowing exceptional monetisation of the deficit.Alongside this, Tunisia also raised domestic revenue via certain new taxes, especially on banks, hotels and liquor firms. Improved terms of trade, driven by lower energy import prices and higher olive-oil receipts, and a tourism rebound helped stabilise near-term balances. This was reflected in the narrowed trade deficit and a state budget surplus in the first half of 2024. The reserves hovered near four months of imports by mid-2024. Further, inflation eased as the central bank cut its key policy rate to 7.5 percent in March 2025, for the first time in five years. A new foreign-exchange code was approved to partially liberalise forex transactions and simplify regulations. A ministerial committee has been set up in coordination with the central bank to oversee an audit of financially distressed state-owned banks as part of a broader plan to reform public banks.

Simultaneously, the government has advanced sectoral initiatives. These include submitting a draft law for establishing an independent electricity regulator that helps attract private investment in renewables, alongside upgrading other energy-sector rules. Infrastructure-development efforts include the World Bank-supported Economic Development Corridor to improve road links and Small and Medium Enterprise financing in interior regions. The building of a new bridge using European and African development funds aims to improve connectivity to the Mediterranean port of Bizerte. Additionally, programmes to strengthen food security and build resilience to climate shocks have been rolled out with the World Bank’s support to complement other measures under Tunisia’s food-security operations.

Over the years, Tunisia has secured non-IMF funding through bilateral partners and multilateral institutions that helped meet its obligations. For instance, Algeria’s US$300 million loan (2021), Saudi Arabia’s US$500 million package (2023), World Bank loans totalling US$520 million (2024) and the African Development Bank’s of €92 million (2024). In parallel, the EU–Tunisia Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) linked substantial support to migration cooperation, with 150 million euros in budget support disbursed in 2024. Rating agencies acknowledged improved short-term liquidity and funding access—Fitch upgraded Tunisia to ‘CCC+’ in 2024, and Moody’s shifted the outlook to stable from negative.

However, there are certain limitations to this strategy. `In the short term, the Tunisian government secured political and financial survival, skillfully navigating a perilous period to avoid a sovereign default. However, the long-term viability of these initiatives remains questionable. Their limitations suggest they could lead to a low-growth trap.

The domestic strategy has been a mix of fiscal stopgaps and slow-moving sectoral reforms. The exceptional monetisation of the deficit is the riskiest and most critical component. This direct central-bank financing threatens its independence, can fuel inflation and crowd out private credit. The World Bank also warned that Tunisia’s increasing reliance on domestic financing may put pressure on the dinar. While the growth rate of Tunisia increased from zero in 2023 to 1.4 percent in 2024, it is still significantly low. Low revenues resulting from this low growth rate continue to impact the budget.

Further, partial financial-sector steps, such as a draft foreign-exchange code to liberalise and simplify forex transactions and plans to audit state-owned banks, are incremental. Without a clear political mandate to implement broader State-Owned Enterprises (SOE) reforms, these moves will not change the fundamentals of the system. Indebted SOEs are forced to cut imports, especially with limited external financials, triggering basic-goods shortages. While inflation has eased, it remains high, particularly for food. This, coupled with rising unemployment, has imposed severe economic hardships on common Tunisians. Governments in the past have dealt with these issues by increasing public employment and food subsidies. These are the exact types of initiatives that have fiscally pressured the country into an economic downfall. Despite the economic stresses, the rise in transfers and subsidies was larger than the marginal fall in the wage bill, as evidenced by Figure 1. Therefore, while sectoral initiatives in food security, energy and infrastructure have helped enhance economic activity and food security, they have long gestation periods. Their benefits will accrue over the years and might be able to plug immediate fiscal holes.

FIGURE 1: TRANSFERS AND SUBSIDIES AS A PERCENTAGE OF GDP

Source: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

The non-IMF external funding Tunisia has relied on has helped it meet its near-term obligations, but these bilateral and multilateral loans typically have costlier and shorter terms than concessional financing. Tunisia’s most significant geopolitical lever is the EU-Tunisia MoU, but this relatively transactional model makes fiscal space contingent on Europe’s shifting migration politics rather than Tunisia’s economic fundamentals.

Can Tunisia Recover Without the IMF?

The central question arising from Tunisia’s current strategy is whether it represents a viable, sovereign path to a sustainable economic recovery. History provides a complex guide. Tunisia is not the first nation to reject an IMF programme. Malaysia refused an IMF bailout during the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. It was the only severely affected country to not adopt an IMF programme during the crisis. Data suggests that Malaysia’s economic policies since have delivered slightly better results than those in countries under IMF programmes, although many have argued that it could have fared even better with IMF assistance. Thus, there is a historical precedent for Tunisia that a path to recovery exists without the IMF.

But Tunisia in 2025 is not Malaysia in 1997. Malaysia had a stronger state capacity and a diversified, export-oriented economy that could implement and absorb measures, as documented by the IMF. Tunisia’s economy, in contrast, is structurally rigid, with a very large state footprint—there are 111 SOEs and public institutions. A Malaysian-style unilateral reform push is unlikely, as the political incentives in Tunisia make tougher but more impactful reforms difficult to implement. The powerful UGTT union, for example, has publicly opposed key measures such as subsidy cuts, wage-bill restraint and SOE restructuring.

Given these realities, the current trajectory is one of survival, not sustainable revival. Tunisia has plugged gaps with ad-hoc external financing and domestic reforms, but these arrangements are fragile and insufficient. Crucially, this mix has not catalysed the private investment Tunisia needs. The World Bank underscores that financing conditions remain tight, crowding out private credit and deterring investment.

A sustainable path should reconcile political red lines with economic imperatives. Full implementation of the IMF programme may be politically infeasible, but a phased, domestically owned sequence offers an alternative. Implementing transparent SOE reforms and shifting from generalised price subsidies to targeted cash transfers can protect the vulnerable. Without a strategic pivot of this kind, Tunisia risks winning the battle for sovereignty but losing the war for solvency.

Samriddhi Vij is an Associate Fellow, Geopolitics at the Observer Research Foundation- Middle East.