The 15th BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) Summit in Johannesburg, South Africa, culminated with the group’s member count having increased from five to eleven. The six new members include four nations from the Gulf and West Asia—Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Ethiopia and Argentina, from Africa and South America respectively, were also admitted. Notably, more than 40 countries from the Global South have conveyed their willingness to join, with at least 22 formal applications. This article contextualises the grouping’s expansion considering its diminishing relevance.

The BRICS grouping

Although originally conceptualized in 2001 by Jim O’Neill, then chairman of Goldman Sachs Asset Management Company, the creation of BRICS can be traced to a meeting of Foreign Ministers of Brazil, Russia, India, and China in 2006. The venture gained traction through more periodic convenings beginning in 2009, resulting in the group’s augmentation with the induction of South Africa in 2010, consequently converting BRIC into BRICS.

The six new members include four nations from the Gulf and West Asia—Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

As per some observers, the BRICS has deftly negotiated past multiple hurdles and is currently viewed as a possible alternate discourse to the G7, a grouping overwhelmingly led by Western nations. The BRICS has positioned itself decisively on numerous issues such as climate action targets, United Nations reform, and unilateral financial sanctions imposed by the West against Iran, Russia, and Venezuela. Further to setting up the New Development Bank (NDB) in 2015, which has funded roughly 100 programmes till date, executing a Contingent Reserve Arrangement, and initiating different institutional architectures, the BRICS countries have exhibited their wherewithal to partake in practical ventures.

Underwhelming accomplishments

Notwithstanding the above, the BRICS has not collectively accomplished anything noteworthy despite its yearly meetings. The NDB has sanctioned only US$ 33 billion worth of programmes since its creation. In contrast, the World Bank commits more than three times that amount in a single year. This is unsurprising since the BRICS is not a very strong bloc economically. It attempts to integrate an existing economic behemoth in China with an emerging power in India and three much smaller economies reliant on commodity exports. The geopolitical tension between China and India, which has manifested in periodic border flare-ups, is one cause for BRICS’s underperformance. New Delhi views China as its most potent rival. With the world’s second largest economy, it is also difficult to see China as an advocate for the Global South. Further, most developing nations would not like to be coerced into choosing camps during an escalation between China and the United States (US).

The geopolitical tension between China and India, which has manifested in periodic border flare-ups, is one cause for BRICS’s underperformance.

Even on the currency front, while many developing nations would like to decouple their economies from the US dollar given inter alia the volatility caused in their economies by the Federal Reserve’s mood swings, they also desire alternate havens to park their foreign exchange assets after Russia’s exclusion from the SWIFT payments system. But neither China nor India possesses a fully convertible currency, limiting the appeal of the RMB and the INR respectively. The BRICS, in fact, is not remotely viable as a monetary union. Its constituents are extremely different with respect to foreign trade, economic growth, and global integration of capital markets. While Russia’s economic performance lagged that of all other BRICS members in 2022, Brazil and South Africa have also been enduring hardships without resilient commodity prices supporting benign interest rates and increasing the creation of domestic credit.

Declining relevance

As a grouping that desires a shared goal, the BRICS is struggling for sustained relevance. There is no common bedrock but their search for cohesion toward achieving a measure of collective salience in the international geopolitical arena remains. As things stand, the BRICS seems to arouse some intrigue due to the ongoing friction between China and the US, as well as Russia’s long-drawn war against Ukraine. This interest in the bloc, however, significantly transcends the public discourse its constituents maintain in the grouping. While each member has cause for persisting within the bloc, the issue is that these are insufficient to convert the grouping into an effective amalgam, let alone changing the world order.

As things stand, the BRICS seems to arouse some intrigue due to the ongoing friction between China and the US, as well as Russia’s long-drawn war against Ukraine.

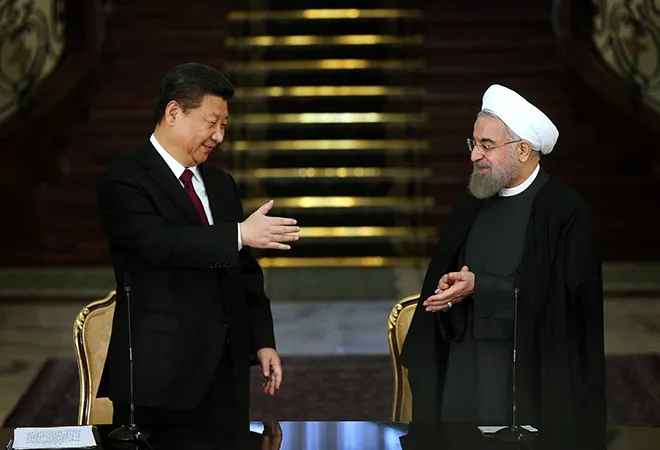

At the grouping’s inception, Beijing had the unambiguous objective of catapulting China’s international stature and yet maintaining proximity with its principal rival—India. Current Chinese President Xi Jinping, on the other hand, has significantly diminished the grouping’s aim, by attempting to reposition it as but one forum among China’s multiple international dominance gambits such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Together with Beijing’s bilateral developmental cooperation with developing nations, this has resulted in the dilution of the BRICS’ objective.

The expansion

The BRICS will struggle to gain relevance despite the addition of new members. It is only Beijing that sees an opportunity to meaningfully enhance its geopolitical influence by admitting Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE into the grouping. China, today, is an important partner of the Ayatollah-led Iran. Beijing has rejuvenated the Iranian regime and set up lines of credit using which the latter makes regular payments in terms of oil barrels. For Iran, BRICS membership provides an excellent opportunity to obtain a conducive forum for expressing itself and defending its domestic manoeuvres. While Saudi Arabia does not face economic problems and geopolitical isolation like Iran, the space conceded by Washington in its ties with Riyadh was promptly exploited by Beijing. Expressions of Western disapproval and concern regarding the suppression of human rights, drive Riyadh and Beijing close in a mutual narrative of contention. This, along with Chinese cooperation in its economic diversification programme, including exploring uranium reserves, makes BRICS membership useful for Saudi Arabia.

Recent economic chaos has manifested in the ransacking and looting of supermarkets and retail outlets in Buenos Aires.

For Argentina, BRICS membership provides cover for the adverse situation domestically. Recent economic chaos has manifested in the ransacking and looting of supermarkets and retail outlets in Buenos Aires. With the nation in turmoil, the opportunity to partake in a global bloc including affluent countries could not be refused. For the remainder, the chance of bilateral annual convenings with President Jinping appears an attractive proposition. In recent years, in fact, such high-level bilateral convenings have been a prime attraction of BRICS summits, and there is no denying that the BRICS provides an appealing forum for networking.

Conclusion

All proposals at the BRICS Summit such as de-dollarisation and yuanisation, as well as establishing alternative lines of credit to those extended by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, are already being implemented by China bilaterally with various countries. China, cunningly, repackages initiatives already being implemented by Beijing, as collective programmes.

The NDB cannot conceivably overshadow these customised credit offerings and thereby endures as a supporting source of credit, overwhelmingly influenced by Beijing.

Yuanisation is being implemented irrespective of the BRICS. Russia has adopted the yuan for purposes of international trade. Iran-China trade utilises the yuan as a benchmark, while credit line arrangements between Beijing and Buenos Aires involve yuan-based transactions along with other currencies. On the credit line front, Beijing extends large-scale funding through the BRI and its Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. The NDB cannot conceivably overshadow these customised credit offerings and thereby endures as a supporting source of credit, overwhelmingly influenced by Beijing. Finally, even after the admission of new members, it is only India that retains significant independence as a country within the grouping—having rebuffed the BRI, while the rest are likely to become more dependent on China. This alone raises a fundamental doubt regarding the bloc’s importance moving ahead.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Aditya Bhan is a Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.