China’s caution in the Middle East endures. As US influence wanes and Gulf states diversify defence ties, Beijing may expand its role—but not replace Washington.

Security in the Middle East has undergone significant shifts since Hamas attacked Israel on 7 October 2023. Israel’s expansionist policy is forcing regional countries to recalibrate their perception of (in)security, underpinned by the ongoing war in Gaza, the strikes against Iran’s nuclear facilities, the confrontations with Hezbollah in Lebanon, the new Syrian government, and the Houthis in Yemen.

Israel’s strike against Hamas negotiators in Qatar on 9 September 2025 has altered the Gulf states’ security outlook. The United States (US) is no longer seen as a reliable security guarantor. Both Israel’s strike and Iran’s targeting of Al Udeid airbase in Qatar during the 12-day war have depleted any remaining confidence in the “protection for oil and trade” model with the US. Gulf states are intensifying diversification in their defence partnerships. For instance, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan’s mutual defence agreement, signed on 17 September 2025, marks a paradigm shift in the Gulf’s defence posture and opens the door for more external security actors to establish a footprint in the region.

Israel’s strike against Hamas negotiators in Qatar on 9 September 2025 has altered the Gulf states’ security outlook. The United States (US) is no longer seen as a reliable security guarantor.

Decline in Washington’s hegemony is expected to align with the interests of its competitors, particularly China. Yet, despite the strong appeal, China is unlikely to take advantage of this low-hanging fruit and will continue to be reticent about playing a major security role in the region.

Shifting Sands

In theory, the new security dynamics in the Gulf can lead to diversification and inclusion—principles that align with China’s policy preferences. Since US President Donald Trump’s return to the White House in 2025, it has become evident that the Gulf States’ efforts to influence the administration’s policy towards de-escalation are undermined by what the author calls ‘Israel’s exceptionalism’ in US Middle East policy that exempts Tel Aviv from complying with the rules of the game. Since Trump’s high-profile visit to Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in May 2025, the strategy of Israeli Prime Minister (PM) Benjamin Netanyahu’s government has been anchored towards ending the aspirations for a Palestinian state and reshaping the regional order.

The rising insecurity in the Gulf states creates incentives to search for alternative security frameworks. This is not a result of strategic intent, as most Gulf countries still prefer to deepen their security partnership with the US. This was evident in Qatar’s prospective enhanced defence cooperation agreement with Washington, which was announced after the strike. It was born out of the necessity of pursuing strategic autonomy.

Regional instability does not serve China’s position in the region. China’s regional footprint is underpinned by energy and infrastructure cooperation, economic statecraft, and partnerships in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and data centres. China imports approximately 45 percent of its oil from the region, a significant factor in Beijing’s energy security. During the 12-day War with Israel, Iran threatened repeatedly to retaliate by closing the Strait of Hormuz. This created a new ‘Hormuz Dilemma’ for China, given the futile alternatives and the insufficient time to search for more secure sources. The threat of a broader regional confrontation has shown that Chinese investments and citizens in Israel and the Gulf, as well as trade routes and shipping vessels, are exposed to serious risks in the absence of credible security guarantees.

Decisive Factors

Ironically, the US is perhaps the most significant security insurance policy for China’s interests in the region. This stems from Beijing adopting a security approach that hinges on building influence through economic development, mediating conflicts, and diplomatic positioning at the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). This policy is designed to sustain engagement with the region, with a limited contribution to hard security, and mitigate risks.

The Middle East has long been a significant energy source and has recently served as a source of diplomatic support for China against Taiwan, as well as a testing ground for Beijing’s governance and ideological offerings in the context of strategic competition.

Despite the limited viability of China’s model during a crisis, Beijing does not seem eager to change its track. In fact, one assumes it does not need to.

Two broad factors are predicating China’s caution. First, the Middle East does not feature at the top of China’s strategic priorities compared to its immediate periphery in the South China Sea (SCS) and the first island chain. The 3 September military parade and China’s assertive military posture around disputed territories in the SCS reflect a determination to reshape the world order to serve China’s interests, starting from the East Asian theatre. The Middle East has long been a significant energy source and has recently served as a source of diplomatic support for China against Taiwan, as well as a testing ground for Beijing’s governance and ideological offerings in the context of strategic competition. However, the dramatic changes in regional security do not affect China’s security or regime stability directly.

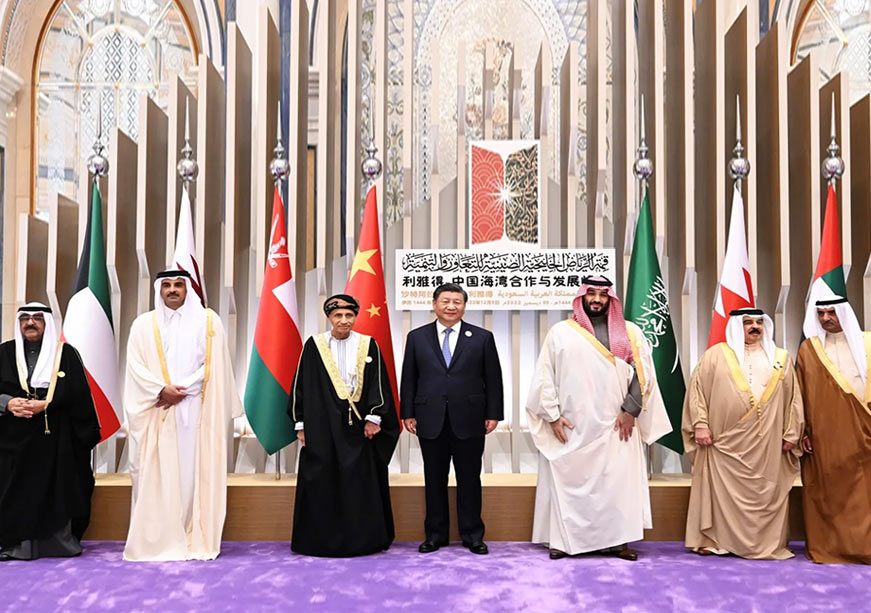

Second, regional security shifts in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) serve China’s interests and undermine the US outlook, as Gulf States’ enhanced agency offers them more options away from exclusive reliance on the US. The core assumption of the Saudi-Pakistan defence deal is that both countries are choosing to diversify away from their security patrons: The US and China. Yet, the implications for Saudi Arabia are more significant, considering China’s relations with Pakistan are not based on a security guarantor model. This is also the case in the Gulf. More strategic autonomy and accelerated multipolarity automatically translate into less US influence and greater adoption of China’s ideas on regional security, even without requiring political alignment with Beijing. China’s call for establishing new security frameworks, such as a “multilateral dialogue platform” in the Gulf as part of the Global Security Initiative, which was announced in 2022, shows China’s support for more indigenous and inclusive security arrangements. This includes dialogue with Iran, especially after the Saudi-Iran rapprochement brokered by China in 2023. The Gulf’s neutral stance during the 12-Day War created the circumstances for a sustained de-escalation and perhaps future security exchanges with Tehran.

The regional shifts seek to undermine the India-Middle East-Europe (IMEC) implementation by encouraging the rise of a regional coalition to balance Israel’s recklessness and shutters prospects for a Saudi-Israel normalisation in the short term. IMEC has been designed to serve as an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Its struggle to take off is certainly a positive development for China.

What next?

The Trump administration’s ad hoc, case-by-case approach to Gulf security, the uncertainty of a sustainable ceasefire and the Trump peace plan for the day-after in Gaza will fuel a sustained review of Gulf states’ security posture during the remainder of Trump’s term in office. An Israeli far-right victory in the October 2026 elections may make normalisation and further integration of Israel in the emerging regional system elusive. On the contrary, it may accelerate the rise of rival alliances to keep Israel’s revisionism in check.

China is also likely to encourage Iran to seek a diplomatic settlement with the Trump administration over its nuclear programme to avoid a regional conflagration, despite the return of sanctions.

These regional shifts mark the end of the Iraq invasion and the Arab Spring era, ushering in a new era in line with broader changes in the global order, moving away from unipolarity. This requires a new security paradigm in the Gulf that may provide other external powers, such as China, a strategic opportunity to challenge the US’s MENA posture.

However, adopting a decisive shift in China’s security posture may not be feasible in the next three years, unless a significant threat to China’s direct interests emerges. Even then, Beijing may be compelled to rethink its MENA security policy in a way that allows it to be an equal player alongside other external security actors and pragmatically focuses on protecting its own interests as a priority, rather than being the primary security guarantor. The latter status would require China to become a security hegemon in Asia and the dominant power in the Indo-Pacific, necessitating a strategic shift in China’s security outlook. This is unlikely to happen anytime soon.

China is also likely to encourage Iran to seek a diplomatic settlement with the Trump administration over its nuclear programme to avoid a regional conflagration, despite the return of sanctions. It may also work with Russia to convince Tehran not to withdraw from the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) or seek a nuclear breakout.

Regardless of the outcome, China will continue to seek alternative sources of energy outside the MENA region to hedge against the risk of war. The Israel-Iran conflict drove the frozen Power of Siberia 2 pipeline. Beijing is likely to explore additional options in the next few years, while accelerating investments in renewable energy sources within the Chinese market to reduce its reliance on imported oil and gas. However, the Gulf will likely remain a significant source of China’s energy imports for years to come.

The Trump administration is likely to impose restrictions on Gulf-China security cooperation, tying any new partnerships in defence and advanced tech to reducing future alignment with China. It may use the end of the war in Gaza to try to revive the Abraham Accords and help turn the Gulf into a future hub for AI and data centres—incentives to shield the region from further entanglement with China. Gulf states are expected to use these developments to accelerate their hedging and maximise benefits from both sides: Intensifying trade and investments with Beijing, while trying to lock in defence treaties and high-tech partnerships with Washington.

The Trump administration is likely to impose restrictions on Gulf-China security cooperation, tying any new partnerships in defence and advanced tech to reducing future alignment with China.

The Gulf security order is changing. By the end of the second Trump administration, more external actors, such as Pakistan, may be expected to play a role in a new multipolar regional order. China may be one of them. However, the expectations it may seek to replace the US as the security provider or directly challenge its preponderance will prove to be futile.

Ahmed Aboudouh is an associate fellow with the Chatham House Middle East and North Africa Programme and Head of the China Studies Unit at the Emirates Policy Center.