Iran’s retaliation for the killing of its top commander Qasem Soleimani was quick. Two airbases housing US troops in Iraq were hit by more than a dozen ballistic missiles from Iran further escalating an already tense situation. Most regional and extra regional stakeholders in the Middle East have been calling for de-escalation and India has been no exception. India’s entanglement in the US-Iran dynamic is not new but this time stakes could be much higher.

Until May 2019, India was the second largest buyer of crude oil from Iran, after China. But after the U.S. ended its sanctions waiver, which had allowed India to import Iranian crude oil, India’s energy ties with Iran have undergone a change. Tehran had previously attracted Indian buyers with lucrative provisions such as free shipping and extended credit, but the U.S. diktat to cease oil imports from Iran has led New Delhi to change its calculus.

In 2018-19, despite mounting US pressures to cut oil imports, India had purchased 479,500 barrels of crude oil per day, more than what it had purchased in the previous fiscal year. After the Trump administration ended its Iran sanctions waivers for a select few countries last year, the U.S. encouraged its oil-producing allies, including Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, to boost production and stabilize the international oil markets, which would have otherwise entered a tumultuous phase due to the absence of Iranian crude oil. In an interesting shift, there has been an increase in India’s oil imports from the United States, outpacing imports from its traditional suppliers in the Middle East.

While purchasing crude oil from Iran has become increasingly difficult for India, New Delhi has ramped up the purchase of crude oil from the U.S. India has also got assurances from the UAE, which has promised to cover for any shortages that India would face owing to the current situation. Continuing tensions in the Strait of Hormuz and the proximate region have made India nervous.

The ongoing crisis could have further ramifications, as India’s dependence on imported crude oil hit a multi-year high of 84 percent last year. Even as consumption has steadily ticked up in recent years, India’s domestic oil output has fallen from 36.9 million tonnes in 2015-2016, to 34.2 million tonnes in the most recent fiscal year, raising concerns in New Delhi about the future of the country’s energy security. It is therefore important for India that the Middle East region remains stable and a military confrontation or conflict wouldn’t serve its interests. India also have extensive trade, investment, security and people-to-people ties with countries in the region. As Indian External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar underlined during his meeting with U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo last year, “energy security is part of it but there are other concerns as well about diaspora, regional security and trade.”

The U.S. sanctions regime has certainly affected India’s relations with Iran, where New Delhi has important strategic and economic interests. In addition to the purchases of Iranian crude oil, which have now been curtailed, these include the ambitious Chabahar port project in southeastern Iran—which India has a major stake in developing—and Indian investments in Iran’s oil and gas sector.

Though India had earlier stated that it only adheres to United Nations sanctions and not to unilateral sanctions by a foreign country, it has been less explicit in expressing its discontent regarding the U.S. policy toward Iran. That is despite the fact that U.S. sanctions have clearly hurt India’s trade with Iran. Indian fossil fuel companies are now hesitant to do business with Iran, and foreign companies, including those from Europe, are refusing to participate in the Chabahar project, slowing its development.

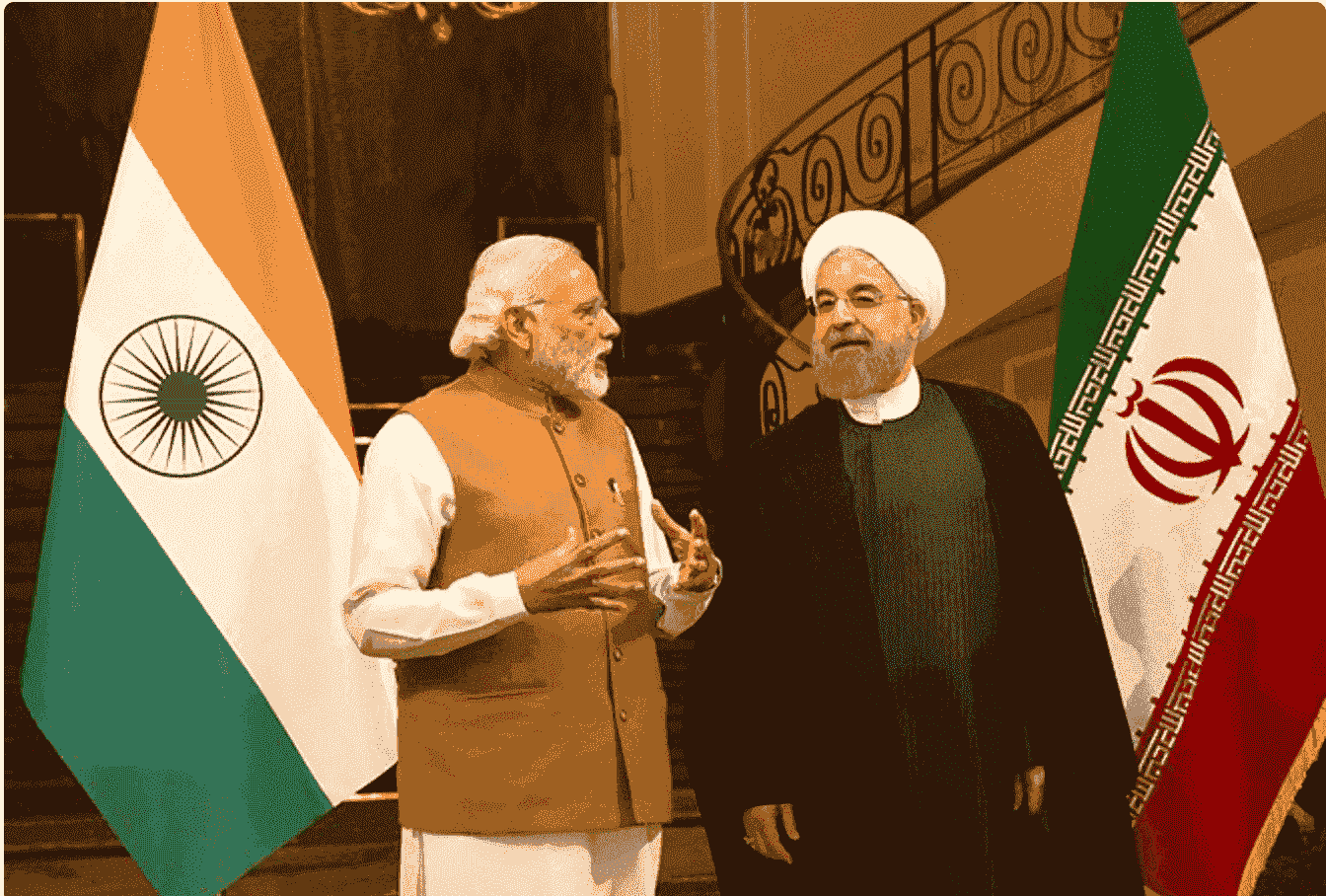

Despite assurances from the U.S. that its sanctions regime would spare non-fossil-fuel-related business between India and Iran, US secondary sanctions target companies which indulge in Iran’s port and shipping sector, which make Indian investments in Chabahar and other associated developments around it vulnerable. Having comprehensive trade ties with Iran is simply not viable for any Indian entity at the moment. Though the U.S. has issued India a waiver to develop Chabahar port, the Trump Administration’s crippling economic sanctions on Iran have ensured that companies remain wary of engaging Iranian ports, resulting in slowing down of trade via Chabahar. Just last month, India and Iran had decided to accelerate Chabahar port cooperation during Jaishankar’s visit to Tehran.

As a result, the Iranian issue has emerged as one big irritant in an otherwise robust Indian-U.S. partnership. The Trump administration’s hawkish position on Iran has made things difficult for Indian diplomacy, though there are signs that Washington is not keen to push the Iran issue beyond a certain point when it comes to Indian-U.S. engagement. During his meeting last year with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on the sidelines of the recent G-20 summit in Osaka, Japan, U.S. President Donald Trump was keen to play down this issue: “We have a lot of time. There’s no rush, they can take their time. There is absolutely no time pressure.”

But New Delhi faces a different timetable. India’s Middle East policy has traditionally tried to balance the three poles in the region: the Arab Gulf states, Israel and Iran. As Trump turns the screws on Iran, this policy that will increasingly become untenable.