The global gas market is entering a structurally softer phase. A wave of liquefaction additions through the second half of the 2020s from the US, Qatar, and Africa in 2026–2028, coupled with slower-than-expected demand growth in Europe and plateauing consumption in China, has reshaped the near-term price landscape. As the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES) report argues, the market is now heading toward a more durable period of US$6/MMBtu LNG by the late 2020s.

For India, which has lived through extreme volatility, including spot Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) above US$30/MMBtu in 2021–22 and significant industrial demand destruction, this shift is more than a macro trend. It represents a rare window to reinforce gas’s place in the energy system after years of stalled growth.

With gas making up just 6.2 percent of India’s primary energy mix in 2024, the question is how much short-term demand can India realistically add in a US$6 world? This article focuses on that near-term assessment, extending through 2035.

India’s Starting Point: A Constrained but Responsive Market

India’s gas sector has long been characterised by asymmetries:

- Stagnant domestic production (~37–38 bcm), which has kept India structurally dependent on LNG imports for meeting incremental demand and leaves little buffer during price spikes

- Under-utilised regasification terminals (56 percent in 2024), reflecting not a lack of import capacity but pipeline gaps, uneven market development, and limited downstream offtake

- Policy-driven prioritisation of Administered Price Mechanism (APM) gas for fertiliser and city gas distribution, which shields priority sectors but leaves industry, power, and petrochemicals reliant on higher-cost LNG

In 2024, total supply reached about 70 bcm, split evenly between domestic production and LNG. However, despite ambitions to raise gas’s share to 15 percent of the energy mix by 2030, most demand segments remain either structurally constrained or highly price-sensitive, underscoring why the US$6 benchmark matters.

Where India Can Respond Quickly

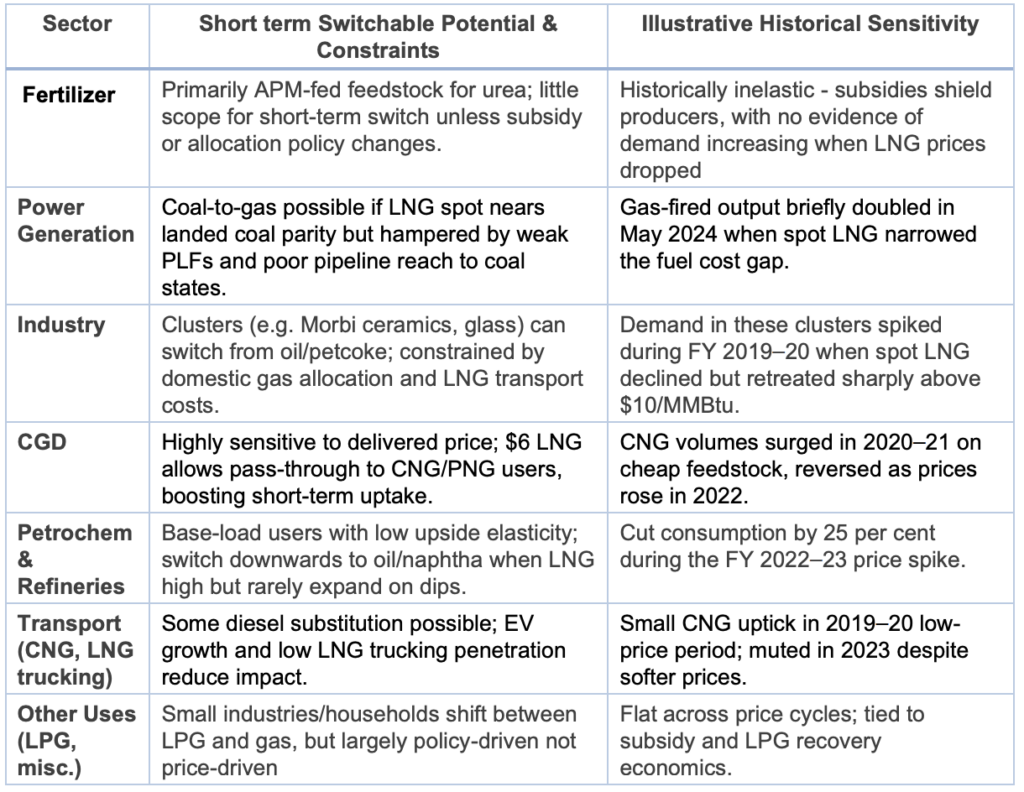

Short-term gas demand hinges on switchability, the ability of sectors to revert from alternate fuels (oil, petcoke, coal, Liquefied Petroleum Gas or LPG) to gas once prices soften. The table below outlines historical sensitivities, but the core insight is clear: India has pockets of highly responsive demand, though they are unevenly distributed.

Source: Author’s Creation

Strong, rapid upside appears primarily in industrial clusters; City Gas Distribution (CGD) commercial and transport segments; and select refinery and petrochemical operations where fuel and feedstock switching is feasible. Peaking power generation can also respond, though only in short, weather or grid-driven bursts rather than sustained runs. Fertiliser, however, remains structurally insulated, APM-fed and subsidy-protected, offering little short-term elasticity.

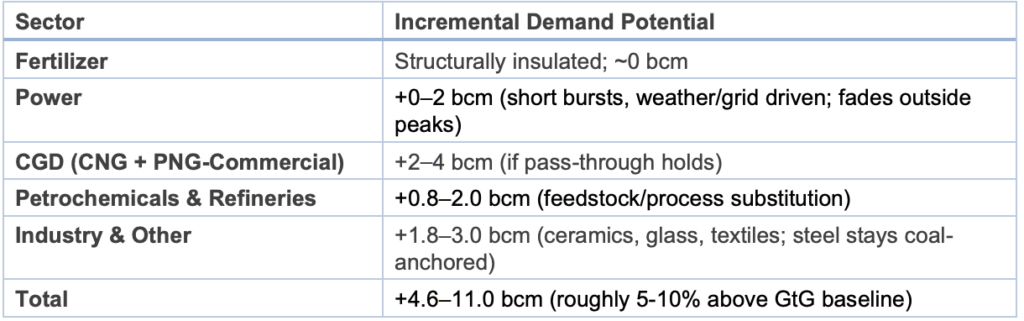

Where the Gains Come From

Source: Author’s Creation

1. Industry: The Fastest Response Zone

If spot LNG stabilises near US$6 in the early 2030s, industry is likely to show the quickest and broadest short-term rebound, especially within existing pipeline and Regasified LNG (RLNG) supply zones. Lower prices materially improve the economics of Piped Natural Gas (PNG) and RLNG for ceramics, glass, textiles, and small manufacturing clusters in Gujarat, Maharashtra, and parts of western Uttar Pradesh, reversing portions of the recent shift toward propane, LPG, and fuel oil.

However, this response depends on effective pass-through of lower prices (including state taxes and levies), RLNG availability at city gates, and timely last-mile build-out. Any move back toward higher LNG prices would quickly cap gains.

A US$6 window is therefore a temporary breather, lifting heat-intensive clusters but leaving structurally coal-anchored steel largely unchanged. The outcome is an opportunistic, uneven rebound rather than a broad-based industrial shift.

2. City Gas Distribution (CGD): High Elasticity When Pass-Through Works

Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) and commercial PNG respond quickly when city gas companies can pass through lower feedstock costs. The challenge is that priority segments continue to receive APM gas, while non-priority customers depend largely on LNG. Thus, CGD’s switchability depends on proper tariff pass-through, stable margins for city gas companies, and on ensuring LNG price declines reach end-users.

At US$6 LNG, the immediate gains arise from higher utilisation of existing PNG networks, especially among small commercial and light-industrial users, and stronger uptake of CNG where low-cost RLNG can offset any APM allocation changes. Most of this upside sits in CNG vehicles and commercial PNG, while household PNG grows more slowly due to connection rollout timelines.

3. Petrochemicals & Refineries: Selective Substitution

Petrochemicals and refineries show downward elasticity; switching away from gas when LNG is expensive and expanding only modestly when prices soften. During 2021–23, several facilities cut gas use or substituted toward alternate fuels, while refineries focused gas use on essential hydrogen units.

If LNG settles near US$6, variable costs improve for hydrogen production and fired heaters, encouraging a partial shift back to gas. Gains remain moderate, constrained by India’s naphtha-based cracker slate, competing off-gases, infrastructure limits, and emerging green-hydrogen obligations.

Overall, a US$6 scenario delivers a meaningful but not transformative uplift, bounded by structural and policy constraints.

4. Power: Episodic, Not Structural

India’s gas-fired power plants operate at very low utilisation, with many units stranded or running minimally. Short-term gains appear only during weather-driven peaks, renewable dips, or coal logistics stresses.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that fuel costs would need to fall to US$5–5.75/MMBtu for gas-based power to be competitive on variable cost. Some stranded capacity can re-enter dispatch during seasonal shortages or grid-balancing events. But utilisation remains contingent on temporary system stresses, not market fundamentals. No new large-scale gas-fired capacity is planned through at least 2032, due to stranded-asset risks, and policy momentum remains firmly behind renewables, storage, and more flexible coal operations.

Under a US$6 LNG environment, gas in power generation produces episodic spikes rather than sustained growth. Even during peaks, total use remains bounded within a narrow range, consistent with OIES projections.

In effect, US$6 LNG makes the sector more responsive but not structurally different.

Structural Constraints That Limit Short-Term Uptake

India’s near-term switchable potential is meaningful, but it is also constrained by fundamentals that US$6 gas alone cannot resolve:

- APM prioritisation leaves little LNG room in fertiliser and PNG-domestic.

- Pipeline gaps reduce the ability of LNG to reach coal-dependent states.

- Underutilised regas capacity reflects last-mile constraints, not import availability.

- EV penetration caps long-term CNG growth in transport.

- Rising long-term LNG contracts (from 22 to 27 MTPA by 2026) reduce short-term flexibility in capturing cheap spot cargoes, as a larger share of India’s import portfolio becomes committed under fixed or formula-linked term deals.

In sum, India can respond to a US$6 world, but only within the limits of infrastructure, regulation, and sector-specific rigidities.

Conclusion: A Short-Term Opening, Not a Structural Shift

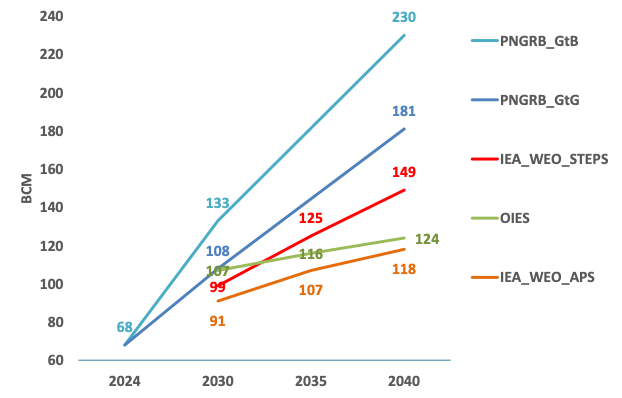

Major forecasting agencies, including the Petroleum and Natural Gas Regulatory Board (PNGRB), IEA, and OIES, converge on a broadly consistent picture for 2030, with national gas demand expected to fall within a relatively narrow corridor (see Figure 1). Despite differing methodologies and long-term assumptions, these projections show similar baseline trajectories for the next decade.

Sectoral sensitivity analysis suggests that if spot LNG prices soften to around US$6 per MMBtu, India could register a short-term uplift above whichever baseline materialises, driven primarily by industry, CGD, and select refinery processes.

Figure 1: India Natural Gas Demand Projections

Source: Author’s Creation

Such elasticity, however, is highly dependent on downstream conditions. Last-mile pipeline connectivity and CGD networks’ ability to absorb and distribute cheaper RLNG are equally critical. Any drift back toward US$8–9 per MMBtu would erode much of the short-term swing, especially in industry and CGD, where demand is most price-sensitive.

In effect, a US$6 spot LNG environment should be viewed as a supportive breather, one that could lift India’s 2030 gas use by roughly 5–10 percent above the PNGRB’s Good-to-Go (GtG) baseline (which assumes moderate growth based on current trends, existing commitments, and expected developments), but not one that alters the country’s longer-term trajectory. The upside is meaningful, yet incremental rather than transformative.

Unlocking any larger structural shift will depend on pipeline expansion, tariff and allocation reforms, better regasification utilisation, and calibrated procurement strategies that balance term and spot LNG.

This analysis draws on the author’s contribution to the OIES report, The Global Outlook for Gas Demand in a $6 World. The full report can be accessed here.

Parul Bakshi is Fellow – Energy and Climate at the Observer Research Foundation Middle East.