Africa’s aspirations for value creation in the domain of critical minerals are constrained by structural bottlenecks, which could be more effectively addressed through regional cooperative frameworks

Seeking value creation from its abundant critical minerals reserves is reshaping Africa’s domestic and international business models. However, structural policy uncertainties and gaps in effective regional collaboration complicate the continent’s transition to the lucrative downstream segment of the critical minerals value chain in the near term. Key gridlocks constraining Africa’s ambitions in the Critical Minerals sector need to be addressed, with potential pathways to value creation emerging through the mitigation of these challenges.

Enhancing Africa’s Critical Minerals Through Beneficiation

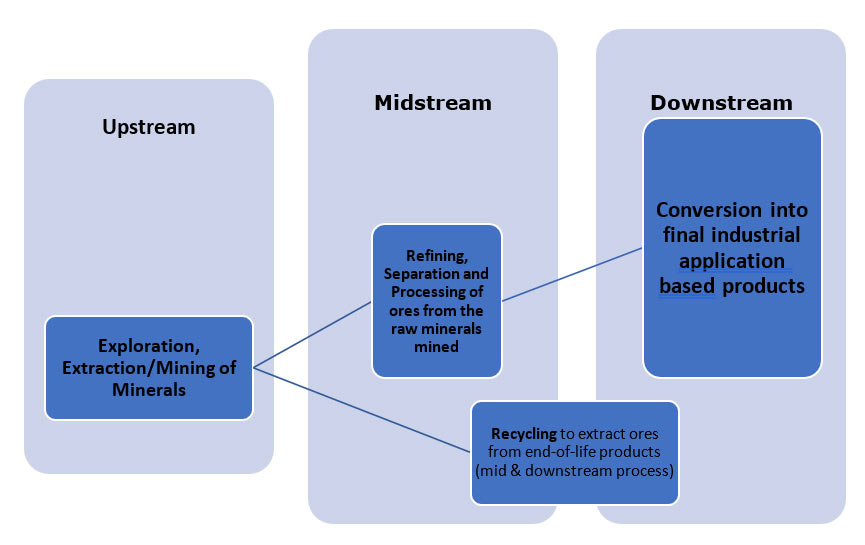

Enhancing the value of a resource or product through further processing is known as beneficiation. In the context of critical minerals, this involves moving beyond the lower-value extractive upstream segment to the more lucrative mid- and downstream segments. Beneficiation, while reducing these countries’ exposure to commodity price fluctuations, offers pathways to diversify their economic portfolios. It also facilitates their integration into global value chains underpinning energy and digital transitions.

Figure 1: Processes involved in each Segment of the Critical Minerals Value-Chain

Source: Author’s own, based on classification from the United States Department of Energy

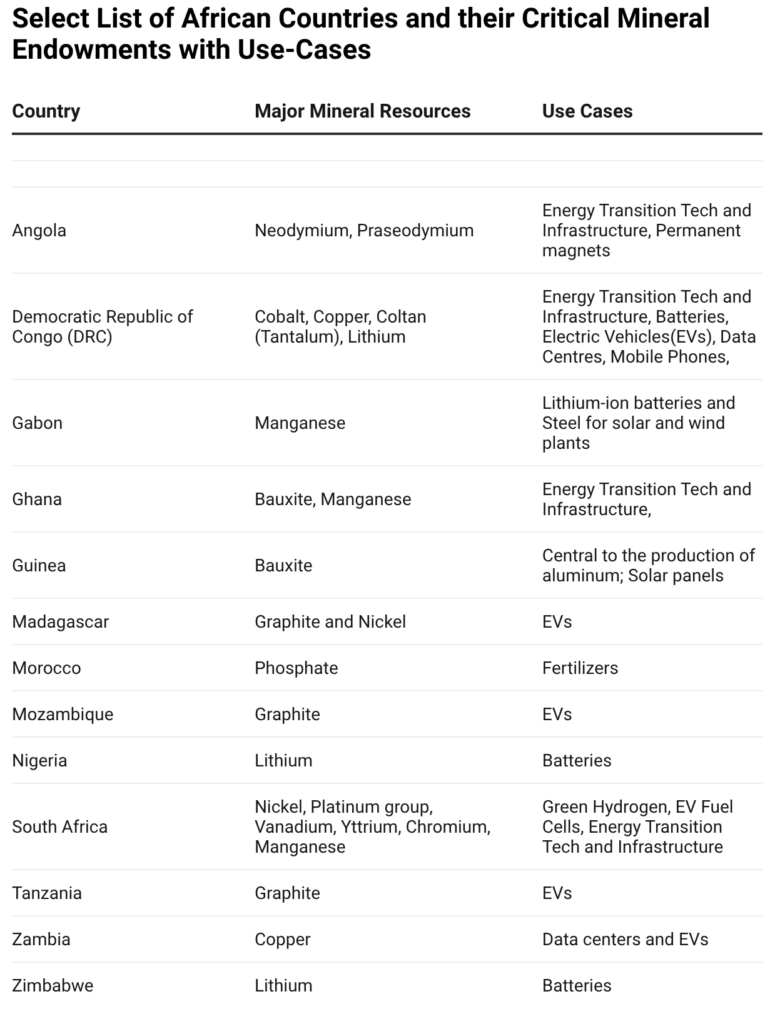

Africa, with nearly 30 percent of global reserves, has been identified as one of the world’s critical minerals super-regions. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that, in a scenario where the Paris Agreement targets are met, the global push towards cleaner energy and industrial applications would drive a 40 percent increase in demand for rare earth elements (REEs) and copper, a 60–70 percent rise in nickel and cobalt demand, and a 90 percent growth in lithium demand.

Figure 2: Select List of African Countries and their Critical Mineral Endowments

Source: Author’s own, based on data from UNCTAD, 2023; IRENA, 2023; (Generated through Datawrapper)

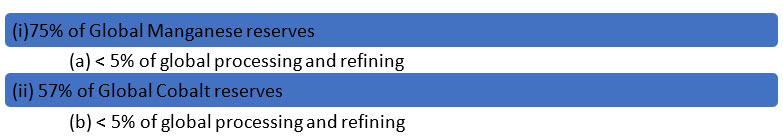

Figure 3: Africa’s mineral reserves vs. processing share (selected minerals)

Source: Author’s own, based on data from (i) SFA Oxford statement; (ii) Cobalt- AfDB report; (a) & (b) International Energy Agency Report, 2025

Structural Barriers to Mineral Value Capture

While the problem set constraining such value creation is not homogenised across the African continent, four broad challenges persist:

First, policy and regulatory uncertainty impacting finance remains the foremost obstacle. While exploration investment in Latin America has increased by a remarkable 200 percent since 2020, it has dropped nearly 80 percent in Africa. Latin America’s impressive turnaround can largely be attributed to the regulatory and policy certainty its countries have established. Conversely, in Africa, policy uncertainties leading to operational inefficiencies have diminished investor confidence.

Policy and regulatory uncertainty impacting finance remains the foremost obstacle. While exploration investment in Latin America has increased by a remarkable 200 percent since 2020.

Second, capital markets price regulatory uncertainties and geopolitical risks at a premium, making financing more expensive. This is significant because mining involves substantial sunk costs and long project gestation periods, yielding slow Returns on Investment (RoIs). Policy reversals in the continent’s fragmented political systems—often influenced by mineral cartels—further compound the risk. Africa’s characteristic model of artisanal mining has also proven difficult to regulate. These factors help explain why the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) for African projects is commonly higher than in other economies. When considering long-term revenue flows from mining that could be reinvested into the sector, it is essential to factor in borrowing costs and debt-servicing obligations that each country assumes with foreign governments or international organisations.

Third, the major barrier arises from regional competition and limited cooperation. Countries compete for the same foreign investment and processing facilities while struggling to collaborate on shared infrastructure or coordinated policy. Regionalism is a key policy determinant in Africa, and multiple cooperative initiatives have been launched, though with limited success. Regionalism is a crucial policy factor across the African continent, and multiple cooperative initiatives have been attempted, though with limited success. The Africa Mining Vision (2009) aimed to ensure the continent’s mineral wealth benefited its own populations, followed by the Africa Mineral Governance Framework (2017) and Africa’s Green Minerals Strategy (2025). However, these vision documents have been easier to adopt in broad policy statements than in detailed, on-the-ground implementation. For example, while countries may agree on the need for a Special Economic Zone, they often struggle with questions over location, regulatory prioritisation, and allocation of employment opportunities.

Capital markets price regulatory uncertainties and geopolitical risks at a premium, making financing more expensive.

The collaboration between Zambia and the DRC on battery and EV production within a Special Economic Zone provides a rare and effective model of successful cooperation in Africa. Yet replication remains challenging due to the high capital expenditure involved. The African market accounts for only about one percent of global EV production. Without sufficient capacity to absorb these high-cost end products, the economics of battery manufacturing on the continent remain unviable

Energy and water scarcity present a fourth major constraint. Much of the continent lacks the affordable baseload power and abundant water necessary for mineral processing. The declining quality of mined ores further increases energy demands for refining and purification. Africa accounts for nearly 600 million of the 730 million people worldwide without access to electricity, and energy infrastructure in many countries is inadequate to provide 24-hour baseload power for effective processing. Seeking additional electricity or water supply in this backdrop poses a significant socio-political and economic challenge, further aggravating the technical gap of energy scarcity

Energy and water scarcity present a fourth major constraint. Much of the continent lacks the affordable baseload power and abundant water necessary for mineral processing.

Finally, infrastructure deficits in smelting, refining, and logistics complete the picture. Africa currently lacks the industrial capacity to smelt at scale and the local talent pool needed for refining and mineral separation. The absence of domestically owned logistics infrastructure from pit to port further limits national control. Without command over the full value chain—from extraction to export—African nations remain vulnerable to external actors who capture the majority of value-added activities, significantly constraining capacity-building on the continent.

Strategic Pathways for Africa’s Critical Minerals Growth

Preferential pricing mechanisms provide an initial pathway to capture greater value. Countries could allocate a portion of locally mined resources to be sold at preferential rates to companies that commit to producing higher-value inputs within the host country or a regional investment hub. To avoid discouraging foreign investors, such preferential pricing should apply to both domestic and international actors, supported by clear long-term land rights and assured compensation in the event of policy reversals. Contract exit costs must be substantial on both sides to ensure compliance.

Preferential pricing arrangements based on competitive bidding could incentivise companies and countries that commit to technology transfer, hardware provision, and transparency. Additionally, countries could create a circular flow of earnings from the sector by reinvesting foreign exchange revenues. For example, rising copper prices could be directed toward developing local smelting capacity and supporting infrastructure.

Creating industrial hubs based on risk-sharing models offers a second strategic approach. Joint industrial and sourcing hubs, even on a smaller scale, can generate economies of scale, address regional capacity gaps, and spread risk, making them more attractive to investors and importers. Such models enable vertical integration that leverages each country’s comparative advantages while avoiding duplicative or wasteful investments. South Africa, with its growing expertise and industrial capacity, could lead the formation of a Special Economic Zone model bringing together Zimbabwe, Zambia, Mozambique, Angola, and Madagascar in the continent’s south. Within such zones, national equity stakes sought by governments could be harmonised through a flat-rate approach tied to demonstrated mid- and downstream contributions. Similarly, examples of countries cooperating on transport corridors like Lobito and Tazara illustrate that bilateral differences can be overcome to enable effective partnerships.

Preferential pricing arrangements based on competitive bidding could incentivise companies and countries that commit to technology transfer, hardware provision, and transparency.

Domestic sourcing and market access mandates offer a third lever. The continent’s demographic dividend—an urbanising population—represents a market well-suited for innovation and technology adoption. Conditioning access to this large market on compliance with local content requirements for high-value goods could significantly strengthen the continent’s role in the value chain. This approach would foster a more diversified industrial base, absorb local talent, and create shorter, more resilient supply chains.

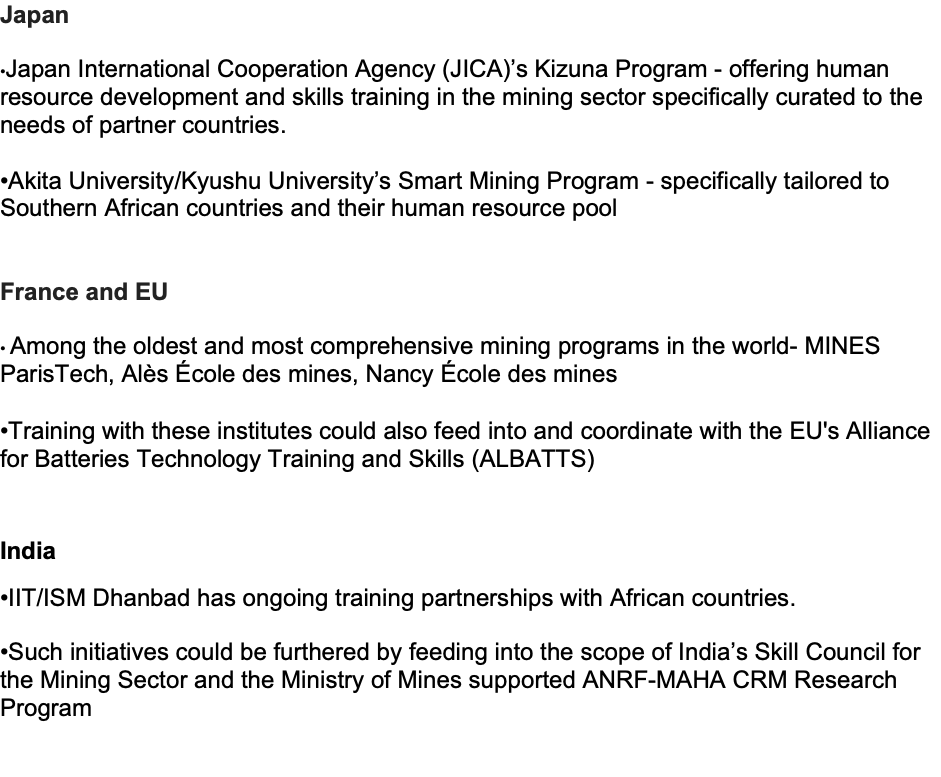

Finally, human resource development and curriculum harmonisation are critical for long-term competitiveness. African governments could implement skills training programs tailored to the mining sector, with tenders requiring the training and absorption of local skilled labour. To make this effective, governments must anticipate technological shifts and update training modules and skill sets accordingly. China’s unparalleled talent pool illustrates how investment in human capital can underpin leadership in the midstream and downstream segments of the critical minerals value chain—a model African countries could emulate. In turn, partnerships with Japan, France, the European Union (EU), and India could bolster the development of human capital in this sector.

Figure 4: Potential Partnerships for Skilling and Human Resource Development

Source: Author’s own, based on data sourced from (i) JICA-Kizuna Program; (ii) Akita University; (iii) MINES Paris Tech; Alès École des mines, Nancy École des mines; (iv) ALBATTS; (v) IIT/ISM Dhanbad partnerships; (vi) ANRF-MAHA CRM Research Program

Ultimately, the absence of tailored regulatory frameworks remains the greatest obstacle to Africa’s value-creation ambitions in the sector. Robust national policies, successfully implemented, could feed into a regional cooperative model that accounts for each country’s comparative advantages and capacity gaps. Coordinated action—leveraging instruments such as the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA)—could significantly enhance the continent’s bargaining power and determine whether beneficiation can be realised meaningfully for African countries.

Cauvery Ganapathy is a Fellow with the Energy and Climate Change Programme at Observer Research Foundation, Middle East.