The United Arab Emirates (UAE) currently imports 83 percent of its food, and its food consumption is expected to rise to 8.8 million metric tonnes by 2029. Bound by high food-import dependence and increased consumption driven by rapid population growth, the UAE government has framed food security as a national priority. It aims to produce 50 percent of its food domestically and secure the top spot in the Global Food Security Index by 2051. However, achieving these goals depends on cultivating a sustainable food system that encapsulates interlinked aspects of food production, distribution, acquisition, consumption, and waste disposal.

The AgriFoodTech sector is rapidly evolving to drive this transformation. AgriFoodTech combines aspects of AgriTech and FoodTech. While AgriTech focuses on leveraging technology to improve production and efficiency of agricultural outputs, FoodTech covers technology to improve efficiency and sustainability of food processing, distribution, and consumption. The UAE’s 2051 Vision for National Food Security Strategy fosters a strong enabling environment to attract investments and spur innovation through its tax-free zones, logistical prowess, and strategic geographic location. Although technology is revolutionising production and logistics across the UAE’s food value chain, it must be complemented by data-informed planning to bridge demand and supply gaps and conducting behavioural campaigns to shift consumption trends. These should also include encouraging platforms that promote catalytic funding and upskilling to equitably scale innovations and integrate them into the broader food system that contributes to long-term food security.

An Overview of the UAE’s AgriFoodTech Sector

Since the launch of the National Food Security Strategy in 2018, the UAE has integrated technology in all its food supply chain stages, from upstream agricultural production and storage, midstream processing, to downstream distribution to consumers.

Hydroponics uses 60 percent less fertiliser and 90 percent less water compared to traditional farming, while precision agriculture enables water-efficient crop growth, leading to higher production.

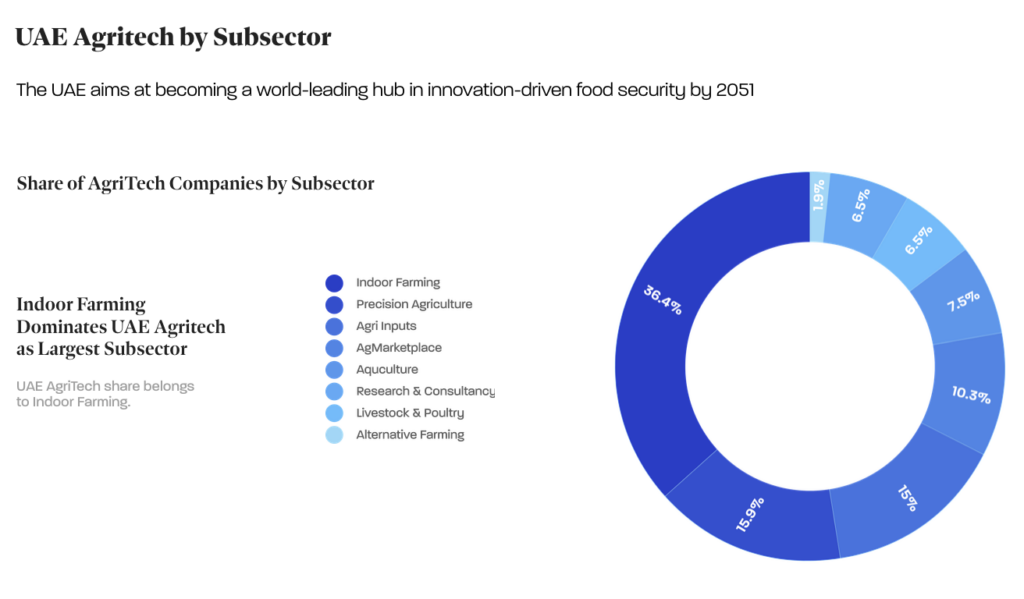

Given the UAE’s arid climate, limited water supply, and extreme heat, alternative farming methods are crucial for increasing resilient crop production. As of 2021, indoor farming composed the largest subcategory of AgriTech companies in the UAE, overtaking precision agriculture that had dominated the market in 2019. Indoor farming uses hydroponics, energy-efficient lighting, and smart technologies to maximise crop production amidst constrained resources. Hydroponics uses 60 percent less fertiliser and 90 percent less water compared to traditional farming, while precision agriculture enables water-efficient crop growth, leading to higher production. Forecasting trends predict the most momentum towards innovations in urban and vertical farming, aquaculture, and technology integration for sustainable food production.

Transferring agricultural products from farm to table requires advancements in logistics and transport to bolster supply chain resilience from extreme climate shocks and to reduce food loss. Source International’s Jebel Ali hub, for instance, combines solar-assisted cooling, IoT sensors for environmental monitoring, and automated guided vehicle systems to maximise delivery capacity.

On the consumption end, the expansion of digital platforms such as e-commerce, ghost kitchens, and subscription-based meal kits facilitates widespread and rapid consumer access. This shift has led to the development of last-mile centralised packing centres, temperature-controlled vans, and route optimisation software to reduce the transit time of food delivery. The UAE’s food delivery market is forecasted to reach US$2.79 billion by 2026, in tandem with the rise of smartphone adoption and rising income households.

Figure 1: UAE AgriTech by Subsector

Source: UAE Investor Navigator

Challenges and Policy Considerations

Amidst this acceleration, several challenges must be addressed to ensure technology enables progress towards food security.

First, there is a disconnect between tech-driven supply and consumer demand. The current AgriTech market is motivated by a need to enhance crop productivity and cultivation, but consumer demand expectations do not entirely align with AgriTech-enabled crop outputs. Although 65 percent of consumers are inclined to seek sustainable and healthier food options, and reports suggest declining meat consumption, studies note that only 21 percent of Emirati respondents would consider a complete shift to plant-based alternatives. Reluctance towards adopting alternative proteins like cultured meat is linked to cultural habits and religious beliefs, which significantly influence dietary decisions. Cereals also lead in the most consumed food category, comprising 39.8 percent of total consumption. However, existing high-tech innovations such as hydroponics and vertical farming cultivate a limited leafy green selection, with 80 percent of crops being lettuce, spinach, broccoli, cucumbers, or peppers. Startups are leveraging aquaculture to explore alternative proteins like tilapia (a type of fish which is easiest to breed) and experimenting with plant-based options, under the consensus that livestock production contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions. Consumer demand for these protein alternatives remains low and inconsistent. This is further compounded by the fact that leveraging AgriTech for local production instead of importing is energy-intensive and 25 percent more costly. There are promising initiatives like Sharjah’s wheat farm, that is cultivating high-protein grains to meet demand for staple products. Further strengthening research on consumption patterns and implementing behavioural interventions will help align AgriTech supply with demand.

The current AgriTech market is motivated by a need to enhance crop productivity and cultivation, but consumer demand expectations do not entirely align with AgriTech-enabled crop outputs.

Another issue lies in the tension between increased accessibility enabled by AgriFoodTech and the persistence of food waste in the hospitality sector and at the household consumption level. Food loss refers to edible food that spoils before reaching consumers, while food waste is good-quality food discarded by consumers. In the Middle East, the UAE is the third-largest producer of food waste with an estimated annual 95kg of food waste per capita and an average annual household food waste generation of 923,675 tonnes, a third of which occurs at the consumption stage. This waste nearly doubles during large-scale events such as Ramadan. While technology has helped reduce upstream food loss at the production stage, they have also contributed to greater food waste at later stages. The “technology efficiency paradox” notes that while efficiency improves processes, it fails to limit growth in consumption and production. In wealthier regions, food waste persists due to rapid accessibility via grocery stores, restaurants, and on-demand delivery apps. In the UAE, entrepreneurs are addressing this challenge through digital solutions like food cycling apps and redistribution platforms targeted towards the hospitality sector. However, food waste reduction strategies at the household level remain underdeveloped.

Although there has been substantial capital influx to finance AgriFoodTech startups in recent years, the AgriFoodTech boom has largely favoured new market entrants and foreign direct investment. Moreover, many solutions remain in early pilot stages and have yet to be commercially scaled, limiting their impact on domestic food production. To illustrate, Abu Dhabi Investment Office committed over AED 1 billion for foreign direct investment and attracting new AgriFoodTech companies. This trend is largely because only 0.4 percent of the UAE’s population is employed in agriculture, a sector that contributed 0.8 percent to GDP in 2019. With emiratisation in mind, the AgriFoodTech revolution hinges on developing a pipeline of green talent. Although they are a fraction of the population, small-scale farmers should be prioritised in the upskilling process. A study found that small-scale farmers in the UAE experience high costs and technical obstacles, preventing them from adopting precision agriculture technologies. Without continued inclusive financing or upskilling programmes, state-backed investments risk disproportionately benefiting new market players instead of supporting existing producers.

Ensuring AgriFoodTech Meets Food Security Needs

The UAE government has fostered a strong enabling environment for private sector-led AgriTech innovations to bolster domestic food production. To ensure adequate integration of these products within the overarching food system, the UAE must adopt a socio-technical approach by strengthening data collection and bridging the demand-supply gap, implementing behavioural campaigns to reduce waste, and continuing to develop platforms that promote catalytic investments and green upskilling.

The government should pair AgriFoodTech advancements with culturally-sensitive public health campaigns on safe food storage, create demand-side incentives to prevent over-purchasing, and urge at-home composting to divert up to 150kg of waste from landfill.

There are opportunities to strengthen coordination between food value chain segments in emerging AgriFoodTech cities like FoodTech Valley, which is expected to house an interconnected ecosystem linking domestic production and distribution to serve local markets. In September 2025, Food Tech Valley signed two MoUs with Al Seer Group to launch a food logistics hub and with Al Ain Farms Group to improve distribution efficiency and reduce waste. To make these partnerships more effective amid shifting consumer preferences, expanding data collection on buying behaviour can guide pricing and marketing for emerging products like alternative proteins. Moreover, the government should pair AgriFoodTech advancements with culturally-sensitive public health campaigns on safe food storage, create demand-side incentives to prevent over-purchasing, and urge at-home composting to divert up to 150kg of waste from landfill. There is progress through the UAE’s partnership with ne’ma, the national food loss and waste initiative, to lead a comprehensive study on cross-sectoral food waste, to reduce it by 50 percent by 2030. Promoting coordination between upstream, midstream, and downstream sectors will also help to implement waste valorisation loops to treat food loss and food waste (FLW) across the entire value chain.

Moreover, increasing catalytic investments, technical assistance, and training for small-scale farmers will help balance the AgriFoodTech enterprise landscape and facilitate project commercialisation. The Emirates Development Bank’s AgriTech Loans programme allocates AED 100 million to support local suppliers in adopting technologies. Additionally, Emirates Growth Fund targets UAE-based small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that experience challenges with scaling pilots to commercially viable operations. Moreover, partnerships like Khalifa University and Silal support university students and farmers in advancing agricultural research and development.

Conclusion

Although AgriFoodTech is a significant component of the UAE’s national strategy to bolster domestic food production and food security, it will only prove to be practical if nascent technologies successfully scale and meet local demands. Forthcoming solutions must continue to be culturally-sensitive, locally-inclusive, and paired with strategies to balance accessibility and FLW prevention.

Leigh Mante is a Junior Fellow, Climate and Energy at ORF Middle East.