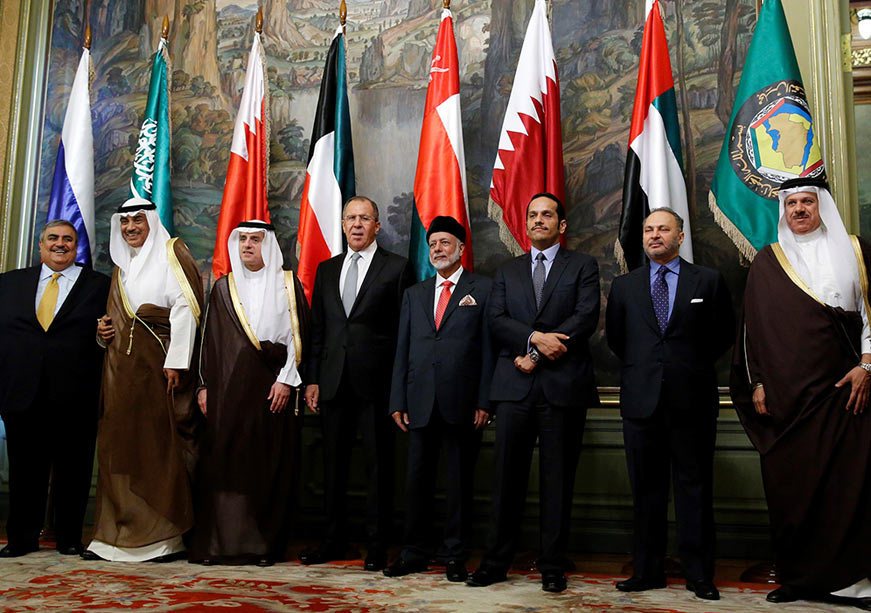

Russia–GCC relations are strengthening. Last month’s Russia–GCC Strategic Dialogue and the launch of scheduled direct flights between Saudi Arabia and Moscow are just two recent examples of this growing engagement. Strengthening the relationship is mutually beneficial: Russia needs partners since it remains cut off from the West, and the Gulf states seek multi-alignment in the changing global order. Yet the partnership is best understood as one of pragmatic, issue-based cooperation rather than strategic alignment, with a legacy rooted in the Cold War.

Historic Foes to Reluctant Partners

The Russian Empire was a key rival of the Ottoman Empire, which encompassed most of the Arab world, but the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 and the creation of a new Middle East divided into European colonies and zones of influence paved the way for limited cooperation rooted in anti-imperialism. One of Vladimir Lenin’s first acts as the new Soviet Union’s leader was to publish the secret Sykes–Picot agreement that the Bolsheviks had discovered between the British and the French, which detailed plans contradictory to the promise of an Arab state made to Hussein bin Ali, the sharif of Mecca and the leader of the Arab revolt against the Turks.

The USSR’s revisionist communist ideology, however, limited its ability to make significant inroads in the region. This began to finally change in 1956, though, when Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, one of the leading figures in the Arab world at the time, turned to Moscow after Washington backed out on its offer to build the Aswan Dam.

The Gulf was more challenging for the Soviets to enter. The 1963 coup d’état in Iraq, which had been a friendly regime, provided an opening, and relations with the newly independent Kuwait, which feared the new government’s territorial ambitions, were established later that year despite the USSR having vetoed Kuwait’s entry into the United Nations just two years prior. Still, the USSR remained unpopular in the eyes of the other states, especially given its support for the Marxist Leninist regime in South Yemen and engagement in Oman’s Dhofar War, in which the Sultan’s Armed Forces fought a Marxist insurrection.

The establishment of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) finally provided an impetus, given the USSR’s status as the largest non-OPEC oil producer. Despite Soviet efforts to gain a foothold in Saudi Arabia, cooperation was limited to the extent necessary to ensure the stability of the global oil market. In addition to coordination on pricing, this also meant that Saudi Arabia provided at least US$1.2 billion in crude oil to Soviet clients to cover obligations that Iraq was no longer able to fulfil during the Iran–Iraq war, for example.

New Opportunities and Challenges in the Post-Soviet Era

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Moscow finally established diplomatic relations with all remaining GCC countries. In the lead-up to the Gulf War, the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, spent weeks engaged in a “diplomatic marathon” in the region to prevent US-led military action, and President Vladimir Putin’s vocal opposition to the 2003 invasion of Iraq a decade later again echoed Soviet anti-imperialist engagement with the Arabs a century earlier. For a Russia weakened by the collapse of the USSR, maintaining an international system that favoured multilateralism over the unilateral use of power by a superpower was a strategic necessity.

Russia’s continued support for the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria, however, caused a cooling in relations in the early 2010s. The alliance with Iran, which strengthened after the collapse of the USSR, further strained relations. While the Assad regime is no longer a point of contention, Iran is still perceived as one of the primary threats to the Arab Gulf countries despite its current weakness and Tehran’s rapprochement with Saudi Arabia in 2023. The 12-day Iran-Israel war may have revealed the limits of Tehran’s partnership with Moscow, but the two countries’ international isolation and recent military engagements seem to be pushing them together nonetheless.

Counterterrorism has emerged as a new area of cooperation. Islam is the second largest religion in Russia and the dominant religion in Azerbaijan and the five post-Soviet ‘Stans’ in Central Asia, which Moscow continues to view as a vital part of its sphere of influence. Islamist extremism has a significant potential to spread and threaten Russian interests. The Chechen conflict made the need for cooperation especially clear, since Chechen separatists drew significant support from transnational terrorist networks like al-Qaeda, with much of the funding passing through the Gulf. Joint counterterrorism efforts have included information sharing and even international multilateral cooperation under the UN Joint Plan of Action.

At the same time, the Gulf may have begun to compete with Russia beyond the region. The Gulf states have engaged with the Horn of Africa for centuries, but their presence on the continent has expanded significantly in recent years. The UAE is now the fourth largest source of capital after the EU, China, and the US. Russia, too, is a major player in Africa. In Sudan, for example, it has thrown its weight behind the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF), a move that has enabled it to secure permission to establish its first naval base in Africa and solidify its presence along regional corridors, but one that may clash with some Gulf interests. The GCC countries are also expanding their presence in Central Asia, which could allow the region to decrease dependence on Russia and Turkey.

A Growing Partnership

As Russia–GCC relations continue to deepen, the focus is now on expanding cooperation in the economic sphere, but also tourism, education, and culture. Trade reportedly increased sevenfold between 2021 and 2024. Since trade was a mere US$7.6 billion in 2021, however, Russia still lags far behind China, the EU, India, and other top GCC trade partners, and a significant portion of the increase reflects Gulf imports of cheap Russian oil sanctioned by the West. Public opinion nevertheless seems promising: A 2025 Saudi poll found that 57 percent of respondents believed it was important to maintain good relations with Russia, noticeably higher than in previous years.

Russia’s war in Ukraine has given relations new momentum. Despite Western pressure, the conflict has put Gulf countries in a powerful position as energy exporters. They maintained a neutral stance and became destinations for both people and companies fleeing the war, even benefitting economically by importing and re-exporting Russian oil. Continuing relations with Russia lends credibility to their multi-alignment strategies and their claims to being impartial mediators. This can benefit the West, too, as the GCC can help bring Russia to the negotiating table. The Gulf countries have already mediated multiple deals to return prisoners of war, and Saudi Arabia hosted the first round of US–Russia talks on ending the war.

At the same time, as the world transitions to a new global order, Russia is also serving as a partner for the Gulf in multilateral institutions like the BRICS. The UAE joined BRICS in 2024, and Saudi Arabia was invited to join but is still assessing membership. Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the UAE, Kuwait, and Bahrain are also dialogue partners of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), and they may one day be linked to Russia through a free trade agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), which already has a partnership agreement with the UAE and has held talks with Saudi Arabia.

The United States remains the dominant external power in the Gulf, and Russia is far from capable of counterbalancing its influence. As a result, Russia–GCC relations remain in the shadow of US primacy. At the same time, relations are clearly on a path of continuous expansion, driven by shifting geopolitical dynamics and the emergence of a more multipolar order, even if the GCC remains committed to the status quo. Only time will tell how far the trend goes, but for now, the opportunities appear greater than ever.

Lillian Aronson is a Visiting Fellow at ORF Middle East and a Research Assistant at the Hungarian Institute of International Affairs.