he architecture of global economic relations will face further challenges, tests, and restructuring in 2026, as key political leaders continue to put national priorities above mutual benefit as experienced last year. The “reciprocal tariffs” announced by the United States (US) in early April disrupted the global trade flows and unsettled the multilateral system built over several decades.[1] As a result, global players are adjusting to this new reality and altering their behavior beyond tariff measures to safeguard their own interests. Rather than allowing comparative advantage to be the primary determinant of trade flows, geoeconomics, the use of a country’s economic strength to achieve geopolitical, security, and foreign policy objectives, has become the driving force in negotiating trade agreements between the US and its major trading partners. Strategic competition between the US and China has extended beyond tariffs into other domains, including export controls imposed on advanced technologies such as semiconductor chips and their inputs, particularly rare earths and critical minerals.[2]

The reaction of other countries to the disruptions of last year offers a glimpse of the future rebalancing of global trade anticipated in 2026, in three ways. First, traditional allies in the Global North that depend on significant trade with the US, such as the European Union (EU), the United Kingdom (UK), Japan, and South Korea, have negotiated lower tariff rates. However, they have found it difficult to meet the significant investment commitments of billions of dollars into the US that they have promised in return.[3],[4] Second, Global South countries with larger economies, including Mexico, Brazil, India, and South Africa, have pushed back against conditionalities for trade deals that affect national sovereignty such as energy security and judicial independence.[5],[6] Third, countries that sought to reduce their overdependence on the US as the largest market and China as the largest supplier of consumer goods achieved limited success and will struggle to contain the impact of tariffs on their domestic economies in the year ahead.

Rather than allowing comparative advantage to be the primary determinant of trade flows, geoeconomics, the use of a country’s economic strength to achieve geopolitical, security, and foreign policy objectives, has become the driving force in negotiating trade agreements between the US and its major trading partners.

1. US-China Strategic Competition Increasingly Impacts the Global South

The geoeconomic landscape in 2026 will become increasingly complex. While there appears to be a temporary truce between the US and China on the tariff front,[7] strategic competition between the Unit ed States and China over critical technology and its inputs will continue intensifying. For other countries seeking to develop their own capabilities in critical technologies such as artificial intelligence, closing the gap with the two major geoeconomic powers will be come more difficult.

Strategic competition between the United States and China over critical technology and its inputs will continue intensifying. For other countries seeking to develop their own capabilities in critical technologies such as artificial intelligence, closing the gap with the two major geoeconomic powers will become more difficult.

The US-China competition over critical technologies and resources that fuel AI and advanced manufacturing will intensify in 2026. In 2025, both the US and China implemented export controls on national security-related technologies such as advanced semi conductors[8] and critical minerals[9]. This has triggered the latest round of threats of further retaliatory tariffs by the US[10]. The US initially sought to exercise its leverage through restrictions on the sale of advanced semiconductor chips to China by private companies such as Nvidia, which are essential for artificial intelligence (AI) data processing. Europe be came involved in the debate through the takeover of Nexperia by the Government of the Netherlands.[11] The recent rollback of some of the restrictions by the US suggests that its policy will remain unpredictable and fluid in the year ahead.

However, what is clear is that in 2026, countries of the Global South with large critical mineral reserves such as Indonesia and Mexico will leverage their access to natural resources in exchange for lower tariffs and greater investment in domestic processing and manufacturing sectors, capitalizing on the US-China geoeconomic competition to their advantage.[12]

In 2026, countries of the Global South with large critical mineral reserves such as Indonesia and Mexico will leverage their access to natural resources in exchange for lower tariffs and greater investment in domestic processing and manufacturing sectors.

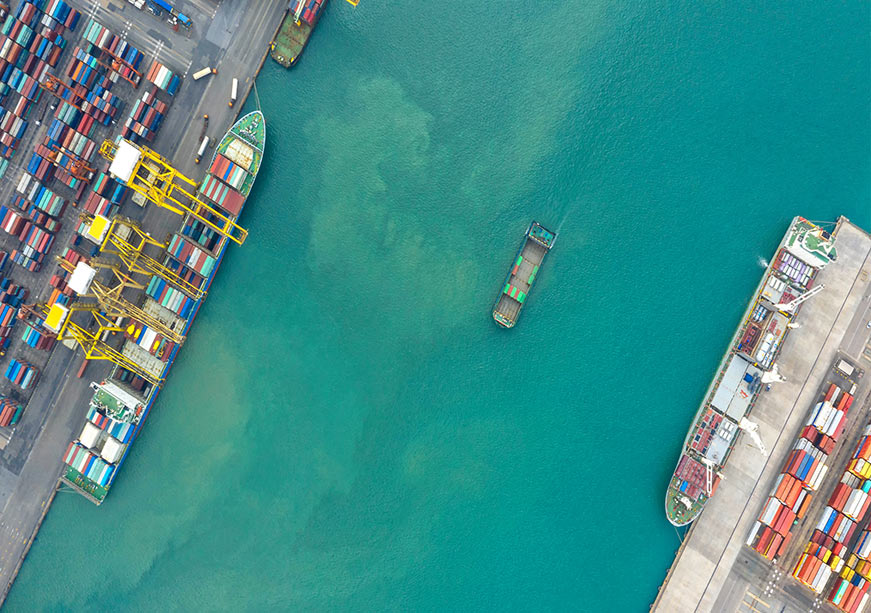

2. China Surges Exports to Global South

China needs new buyers. As the Trump administration continues to limit imports into the US, China will shift its attention toward other trading partners as it continues to expand its domestic manufacturing capacity.[13] China’s annual trade surplus had reached USD 1 trillion by November, due largely to the surge in exports to Asia, Africa, and Latin America.[14] This trend will continue, driven by in creased demand in sectors such as renewable energy, electric vehicles, telecommunication equipment, and consumer electronics, where China’s share exceeds 80 per cent of global supply in some cases.[15]

In 2026, Global South countries will need to balance strategically the benefits of cheaper imports from China with the imperative to protect their domestic industries.

During the last trade conflict between the US and China starting in 2017, several G20 countries imposed import restrictions on Chinese manufactured goods to prevent an influx of “deflected trade” from flooding their domestic markets.[16] In 2026, Global South countries will need to balance strategically the benefits of cheaper imports from China with the imperative to protect their domestic industries.[17] As the US limits opportunities to circumvent tariffs through the transshipment of Chinese goods from the Global South, countries such as Mexico and Vietnam will find it increasingly difficult to absorb cheaper imports from China without putting their own manufacturing industries and jobs at risk.[18]

3. Trade Between Global South Increases

The geoeconomic impact of tariffs is expected to play out in two key ways: an increase in trade across the Global South and greater attention on the corridors and infrastructure that connect them.

As access to developed country markets becomes more restricted, Global South countries will expand trade through bilateral agreements[19], regional blocs[20] and multilateral groupings such as the G20[21] and BRICS.[22] This trend will accelerate through 2026 as the complementarities and linkages within the Global South become clearer and more defined. Intra-Glob al South trade will serve as a hedge against the tariff policy uncertainty in developed country markets. Global South countries will also pursue opportunities for free trade agreements (FTAs) with major developed economies, such as the one between the UK and India, strategically leveraging their markets and comparative advantage in global value chains.[23]

As trade between countries of the Global South grows in 2026, connectivity projects such as the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), 24[24] Masterplan on ASEAN Connectivity 2025,[25] and South Connection linking eleven countries of Latin America will receive a boost.[26] These include not only physical infrastructure to facilitate trade such as roads, railways, and ports, but also energy pipelines, undersea cables, institutional coordination, and cross-border digital payments. At the same time, greater attention will be directed to logistics hubs centered around fast-growing, middle-income countries with established manufacturing exports at key geographical intersections, such as Vietnam, India, the United Arab Emirates, Türkiye, and those in the western hemisphere connecting Latin America with Asia, such as Peru, Colombia, and Mexico.[27]

Greater attention will be directed to logistics hubs centered around fast-growing, middle-income countries with established manufacturing exports at key geographical intersections, such as Vietnam, India, the United Arab Emirates, Türkiye, and those in the western hemisphere connecting Latin America with Asia, such as Peru, Colombia, and Mexico.

4. Industrial Policy Advances

As the initial effect of tariffs and trade agreements over the past year become more evident in 2026, Global South countries will use industrial policy to drive investment to specific sectors, such as critical minerals,[28] advanced manufacturing,[29] and emerging technologies, especially AI and its infrastructure.[30] Governments will escalate protectionist measures to further subsidize domestic manufacturing.[31] Businesses will continue diversifying and de-risking their global supply chains, focusing on countries that are geopolitically rather than geographically proximate.[32] Those countries with substantial industrial bases and endowments of natural resources are positioned to do so most effectively, including Brazil, Indonesia, India, and Mexico. One roadblock to overcome is that some Global South countries are facing rising debt service costs[33] and constrained access to concessional financing,[34] creating heightened risk of a debt-crisis in 2026.

Governments will escalate protectionist measures to further subsidize domestic manufacturing. Businesses will continue diversifying and de-risking their global supply chains, focusing on countries that are geopolitically rather than geographically proximate.

Conclusion

Tariffs and export controls have fundamentally al tered the global trade landscape in the past year. They have been advanced by new US leaders who long dis agreed with the traditional consensus that free trade is a path to mutual prosperity. The world in 2026 will experience the impact of heightened geoeconomic competition as the two major trading powers; the US and China continue to use tariffs and export controls to reshape the global economy to their advantage. Global South countries will need to guard against the flood of imported manufacturing goods from China, safeguarding their national interests through indus trial policies aimed at protecting and creating jobs. At the same time, it presents an opportunity for the Global South to take advantage of the turmoil. The rules of rebalanced globalization remain in the pro cess of being defined. How Global South countries respond to Washington and Beijing with their own geoeconomic initiatives in 2026 is likely to shape the future global economic order.

Endnote

[1] United States Government. “Regulating Imports with a Reciprocal Tariff to Rectify Trade Practices That Contribute to Large and Persistent Annual United States Goods Trade Deficit”, April 2, 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/04/regulating-imports-with-a-reciprocal-tariff-to-rectify-trade-practices-that-contribute-to-large-and-persistent-annual-united-states-goods-trade-deficits/

[2] United States Government. “Ensuring National Security and Economic Resilience through Section 232 Actions on Processed Critical Minerals and Derivative Products”, April 18, 2025. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/04/18/2025-06836/ensuring-national-security-and-economic-resilience-through-section-232-actions-on-processed-critical

[3] European Commission. “Joint Statement on a United States-European Union framework on an agreement on reciprocal, fair and balanced trade”, August 21, 2025. https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/news/joint-statement-united-states-european-union-framework-agreement-reciprocal-fair-and-balanced-trade-2025-08-21_en

[4] United States Government. “Fact Sheet: Implementing the General Terms of the U.S.-UK Economic Prosperity Deal”, June 17, 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/06/fact-sheet-implementing-the-general-terms-of-the-u-s-uk-economic-prosperity-deal/

[5] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. “Statement by Official Spokesperson”, August 4, 2025. https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/39936

[6] Luis Ignacio Lula da Silva. “Brazilian Democracy and Sovereignty are Non-Negotiable”, September 14, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/14/opinion/lula-da-silva-brazil-trump-bolsonaro.html

[7] United Stated Government. “Modifying Reciprocal Tariff Rates Consistent with the Economic and Trade Arrangement between the United States and the People’s Republic of China”, November 4, 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/11/modifying-reciprocal-tariff-rates-consistent-with-the-economic-and-trade-arrangement-between-the-united-states-and-the-peoples-republic-of-china/

[8] United States Government. “Additions and Revisions to the Entity List”, September 16, 2025. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/09/16/2025-17893/additions-and-revisions-to-the-entity-list

[9] Ministry of Commerce, Government of the People’s Republic of China. “China’s recent economic and trade policy measures”, October 13, 2025. https://english.www.gov.cn/news/202510/13/content_WS68ecc859c6d00ca5f9a06bc8.html

[10] Peterson Institute of International Economics. “US-China Trade War Tariffs: An Up-to-Date Chart”, November 10, 2025. https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/2019/us-china-trade-war-tariffs-date-chart

[11] Government of the Netherlands. “Minister of Economic Affairs invokes the Goods Availability Act”, October 12, 2025. https://www.government.nl/latest/news/2025/10/12/minister-of-economic-affairs-invokes-goods-availability-act

[12] United States Government. “Fact Sheet: The United States and Indonesia reach historic trade deal”, July 22, 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/07/fact-sheet-the-united-states-and-indonesia-reach-historic-trade-deal/

[13] Xinhua. “15th Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development”, October 28, 2025. https://english.news.cn/20251028/efbfd0c774fd4b1c8daeb741c0351431/c.html

[14] General Administration of Customs, Government of the People’s Republic of China. “China Customs Statistics”, December 8, 2025. http://english.customs.gov.cn/Statistics/Statistics?page=1

[15] Ministry of Finance, Government of India. “Geo-economic fragmentation replacing globalisation worldwide with backsliding of economic integration”, January 31, 2025. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2097913

[16] Center for Economic and Policy Research. “Redirecting Chinese Exports from the US: Evidence on Trade Deflection from the First US-China Trade War”, April 24, 2025. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/redirecting-chinese-exports-us-evidence-trade-deflection-first-us-china-trade-war

[17] Vietnamnet Global. “Shein and Temu face halt orders in Vietnam without official registration”, October 11, 2024. https://vietnamnet.vn/en/shein-and-temu-face-halt-orders-in-vietnam-without-official-registration-2340709.html

[18] Government of Vietnam. “ASEAN faces challenges as China shifts its trade focus”, October 8, 2025. https://vntr.moit.gov.vn/news/asean-faces-challenges-as-china-shifts-its-trade-focus

[19] Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India. “Brazil-India Joint Declaration for Deepening of MERCOSUR-India Trade Agreement”, October 16, 2025. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2180058

[20] Association of Southeast Asian Nations. “The 57th ASEAN Economic Ministers’ (AEM) Meeting”, September 23, 2025. https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/24.-Joint-Media-Statement-AEM-57-adopted.pdf.

[21] G20. “G20 Trade and Investment Ministerial Statement,” October 10, 2025. https://www.g20.utoronto.ca/2025/251010-trade-statement.html

[22] BRICS. “BRICS Approves Joint Declaration for Fairer, More Inclusive Global Trade,” May 27, 2025. https://brics.br/en/news/brics-approves-joint-declaration-for-fairer-more-inclusive-global-trade

[23] Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India. “Synopsis of Key Chapters of India-UK Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA),” 2025. https://www.commerce.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/India-UK-CETA-Synopsis-of-Key-Chapters.pdf

[24] Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India. “India poised to become a trusted bridge of global connectivity through India-Middle East Economic Corridor (IMEC)”, April 16, 2025. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2122299®=3&lang=2

[25] Association of Southeast Asian Nations. “Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity 2025,” 2016. https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Master-Plan-on-ASEAN-Connectivity-20251.pdf

[26] Inter-American Development Bank. “IDB launches ‘South Connection’ regional program”, March 28, 2025. https://www.iadb.org/en/news/idb-launches-south-connection-regional-program

[27] Allianz. “The geoeconomic playbook of global trade”, 2025. https://www.allianz.com/content/dam/onemarketing/azcom/Allianz_com/economic-research/publications/specials/en/2024/november/14112024-geoeconomic-playbook-global-trade.pdf

[28] Government of Brazil. “Strategic pro-minerals policy”, 2021. https://www.gov.br/mme/pt-br/assuntos/secretarias/geologia-mineracao-e-transformacao-mineral/pro-minerais-estrategicos/FolderPolticaPrMineraisEstratgicosversoingls.pdf

[29] Government of India. “Semicon2025: Building the next semiconductor powerhouse”, September 1, 2025. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressNoteDetails.aspx?NoteId=155130&ModuleId=3®=3&lang=2

[30] OECD. “The OECD.AI Policy Navigator”. https://oecd.ai/en/dashboards/national

[31] Government of India. “Powering the Future: The Semiconductor and AI Revolution”, August 15, 2025. https://www.pib.gov.in/FactsheetDetails.aspx?Id=149242

[32] Ministry of Finance, Government of India. “Geo-economic fragmentation”

[33] The World Bank. “International Debt Report 2025”, 2025. https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/debt-statistics/idr/products?cid=ECR_LI_worldbank_EN_EXT_profilesubscribe

[34] Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. “Cuts in Official Development Assistance: OECD projections for 2025 and the near term,” June 26, 2025. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2025/06/cuts-in-official-development-assistance_e161f0c5/full-report.html